Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. Unconventional Growth May Slow on Continued Capex Losses, Says Oxford Researcher

The U.S. unconventional oil and natural gas industry for years likely will be delineating acreage and increasing efficiencies, but who’s going to pay for it in the long term if large and small players continue to report ongoing losses?

That’s a question that the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), an independent center of the University of Oxford in England has attempted to answer.

Producers large and small have been writing down huge losses in their onshore resources, partly on volatile commodity prices, partly because of exploitation costs, OIES research associate Ivan Sandrea noted. For instance, Royal Dutch Shell plc is selling a lot of its North American onshore properties after taking a $2 billion-plus charge against them in 2013 (see Shale Daily, Aug. 2, 2013). Chesapeake Energy Corp. wrote down more than $2 billion of its property values in the second quarter of 2013; for 2012 it also wrote down $2 billion (see Shale Daily, Nov. 6, 2013; Feb. 22, 2013).

Others taking U.S. asset-related writedowns over the past year have included BHP Billiton Ltd., Devon Energy Corp., Encana Corp., Ultra Petroleum Corp., Southwestern Energy Co., Newfield Exploration Co. and Anadarko Petroleum Corp. More recently, EV Energy Partners LP reported a $50.2 million net loss in 4Q2013 for writing down Permian Basin properties related to commodity prices (see Shale Daily, March 3).

Attempting to squeeze value out of difficult-to-exploit rock and tight resources is going to lead to some hard questions, said Sandrea. His research concludes that players may have to restructure their focus and zero in on the most commercially sustainable areas of their basin holdings. That could lead to lower production growth in the United States than currently is expected or even a more lasting slower growth.

Not all producers are going to win, but shifts in commodity prices and performance improvements “will result in a stable ‘core’ group holding the prize.”

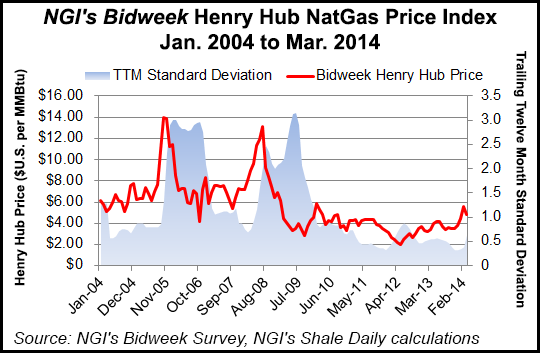

The wide volatility in natural gas prices from 2000 to 2010 has largely subsided, and it appears that prices have recorded steady increases off of historic lows over the last two years, according to NGI data (see graph).

Since 2006, U.S. gas and oil output has responded to high prices and technological innovation, with total production now at a record high — and rising — in several giant plays. Taking a broad consensus, said Sandrea, the unprecedented supply response came from at least four factors: global price increases; drilling of a large number of wells, along with technological advancements in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking); capital and credit availability in the United States, in addition to international funding; and changes in the international business environment, such as the rise in political risk in many countries.

Water availability, type of land ownership, rigs, fracking horsepower availability and regulations are all drivers and enablers of the revolution, he said.

What’s resulted is that capital spending is shooting through the roof. Annual capital expenditures (capex) associated with unconventional gas and oil has risen from around $5 billion in 2006 to more than $80 billion in 2013. In addition, more than $20 billion of mergers and acquisitions, and joint ventures, have repositioned the industry.

Many investment experts consider unconventionals to be a must-have in stock portfolios, and share prices/valuations for many domestic explorers are at record highs, Sandrea said.

“The less talked about, but highly critical questions, are related to the economic model, the viability promised to investors that companies will extract large volumes of resources, and the sustainability of these new plays that have been derisked and are in the development/growth stage.”

To build a scalable industry and ultimately meet long-term U.S. supply increases, exploitation has to be viable commercially for “rational” investors to keep funding the activity “beyond the initial excitement,” Sandrea said.

Yes, there are new opportunities and better well economics. What is not clear from higher-level company data is whether large players and independents are able to run a cash-flow positive business in top quality and marginal plays as industry scales up operations.

A recent analysis covering 35 independents that accounted for 3 million boe/d of production — 40% of the total unconventional production in the United States in 3Q2013 — found that in the past six years financial performance has progressively worsened, Sandrea said.

“This is despite showing production growth and shifting a large portion of their activity to oil since 2010, presumably to chase a higher margin business.” Capex nearly matched total revenues every year, and net cash flow has been moving down while debt continues to rise.

In the near- and medium-term, Sandrea said it has become increasingly evident that the U.S. players are likely to remain challenged by above-ground factors that include more difficult exploitation and the need to secure leases, partially why the writedowns have been made. Below ground, technology and innovation are extracting the molecules more quickly, but on average, the decline curve profile and recovery factors remain “broadly unchanged” for many plays and may weaken as more difficult acreage is targeted.

Drilling in U.S. basins may require decades, not years, to complete, but it’s going to be at a cost.

“The lifetime capex for just the Appalachian and Permian exceed $1.5 trillion,” Sandrea said. “After all, the benevolence of the U.S. capital markets cannot last forever for all players, especially the marginal players, regardless of how deep and specialized the U.S. market is.

“A more realistic outcome is that sections of the industry will have to restructure and focus more rapidly on the most commercially sustainable areas of the plays, perhaps about 40%of the current acreage and resource estimates, possibly yielding a lower production growth in the U.S. than is currently expected, but perhaps a more lasting one. Ironically, this dramatic change may just be what the industry needs to maintain growth. Outside of the U.S., the revolution is still a distant hope.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |