Senate Committee Opens Debate on Possible Crude Exports

The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources opened debate on possible crude oil exports Thursday with what chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) said was the first of many hearings to come and, from the start, there were disagreements on some basic issues.

Ranking Republican committee member Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Wyden “wanted to have this hearing because America’s energy renaissance has sparked a conversation on whether exporting crude oil is in the national interest,” the chairman said in opening the hearing. “I think it’s fair to say this conversation is not going to be resolved any time in the next few weeks.”

Testimony from Continental Resources CEO Harold Hamm and others demonstrated differing opinions on the need for exporting crude and its potential effects on prices at home and the U.S. economy.

It is the technological breakthroughs that have opened the nation’s shale plays to escalating production that make exporting domestic crude possible, Hamm said.

“Not only has horizontal drilling increased America’s supply of crude oil, but also it has improved the quality. Primarily the oil produced through horizontal drilling is light, tight, low-sulfur crude, making it the best quality in the world…the popular belief is that we’re not exporting petroleum, but nothing could be further from the truth. Major oil companies are exporting refined petroleum products like gasoline and diesel with no limitations. Why shouldn’t independent producers be allowed to do the same?”

The United States should actively support open markets by lifting restrictions on its own energy exports, according to Amy Myers Jaffe, executive director of energy and sustainability at the University of California-Davis.

“By leading the charge on new energy technologies and exports, the United States now has the ability to fashion a global energy world more to its liking, where petro-powers can no longer hold American drivers hostage or turn off the heat and lights to millions of consumers in the United States or allied countries to further geopolitical ends,” Jaffe said.

Panelists disagreed about the impact American consumers would feel from crude exports.

“The true benefit to the American consumer will be competition for the refining of gasoline,” Hamm said. “Crude oil is no different than any other commodity, product or service demanded by consumers; lower prices are only brought about by increased supply, greater competition amongst sellers, weaker demand, or improved efficiency in the manufacturing and distribution process.”

Jaffe warned that focusing only on the potential impact U.S. exports might have on gasoline prices in a portion of the country “is foolhardy, given the complexity of interactive forces that will influence prices in the long run.

But, it’s not just gasoline prices. Exporting domestic crude, which currently sells for about $11 per barrel less than crude sold in Europe, could have unexpected negative consequences, putting the U.S. oil market once again under the thumb of OPEC, according to Graeme Burnett, senior vice president of Delta Air Lines. Delta produces jet fuel and other petroleum products at a refinery near Philadelphia that it purchased from ConocoPhillips in 2012.

“The U.S. crude market is a competitive one with price determined by supply and demand. Once the U.S. domestic market incorporated the increased supply of crude from places like North Dakota’s Bakken formation, the price of a domestic barrel of oil came down. In contrast, the global market is influenced by an oligopoly where OPEC [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] control production in order to set prices.

“If we lift the export ban we would in essence be allowing the transport of crude out of a competitive market in this country and into a less competitive global one controlled by a few oil producing states. The results would be easy to predict: U.S. crude would flow out of this country and onto the world market, OPEC would reduce supply to maintain high global prices, the United States’ use of homegrown oil would diminish, and prices here at home would rise to match the higher global price for a barrel of crude…It’s clear who gains from this scenario: the oil exploration and production companies, many of which are foreign owned.”

And there was disagreement about which would benefit the U.S. economy more: exporting crude, or exporting refined petroleum products, with Jaffe and Hamm saying crude exports would lead to more investment and more jobs than growing the nation’s refining capacity, Burnett preferring keeping the added value of refined products in the U.S., and Daniel Weiss, director of climate strategy at the Center for American Progress, saying investments in renewables would have a bigger payoff than either crude or refined petroleum exports.

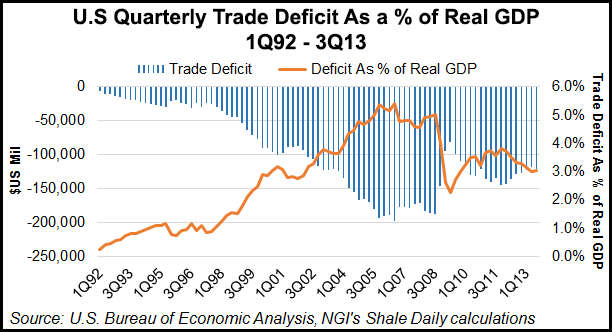

The ability the export crude oil — as well as natural gas — would no doubt help reduce the U.S. trade deficit, which has already been in decline in recent quarters, both in terms of actual dollars and as a percentage of real GDP. The quarterly trade deficit in the United States essentially has been cut in half since peaking in the third quarter of 2006.

During a discussion of ExxonMobil Corp.’s 4Q2013 earnings results Thursday, investor relations chief David Rosenthal was asked for the oil major’s perspective regarding the Senate committee hearing.

“As a company, we fully support free markets, free trade,” Rosenthal said. “We oppose any barriers or restrictions to free trade and [support] open investment across the value chain in the energy sector…Over time, I think it’s pretty clear that barriers to free trade can actually lead to higher prices, dampen economic growth and prosperity and in this case could potentially harm energy security by limiting diversity of supplies.”

Free trade is the “best way,” he said, to maximize the economic value of any enterprise, including the oil and gas industry, which “generates the most jobs, generates the most revenue to the taxing authorities…

“We would not advocate putting any restrictions at any point along manufacturing value chain, even if it might benefit some part of our business.”

A crude oil glut could arrive before the U.S. government makes any significant change to export policy, according to analysts at ClearView Energy Partners LLC.

“We believe Congress represents the most likely forum for a change in crude and condensate export policy, but we expect that the process could take years in the absence of (currently unlikely) support from the White House,” the analysts said in a note Thursday.

OPEC Secretary General Abdallah Salem el-Badri said this week that the cartel doesn’t feel threatened by the United States producing ever-increasing volumes of shale oil, and one OPEC member, the United Arab Emirates, said it was interested in possibly importing natural gas from North America (see Shale Daily, Jan. 27). OPEC acknowledged that growing U.S. shale oil production would displace imports from its member states in a report issued last July (see Shale Daily, July 12, 2013). Separate reports released earlier in 2013 by the International Energy Agency and IHS Inc. arrived at the same conclusion (see Shale Daily, May 15, 2013; Jan. 25, 2013).

The U.S. Energy Information Administration recently said rising crude oil production in the United States helped stabilize global prices for crude oil in 2013 and kept them close to the same annual average

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |