Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Operators Developing West Virginia at Steady Pace

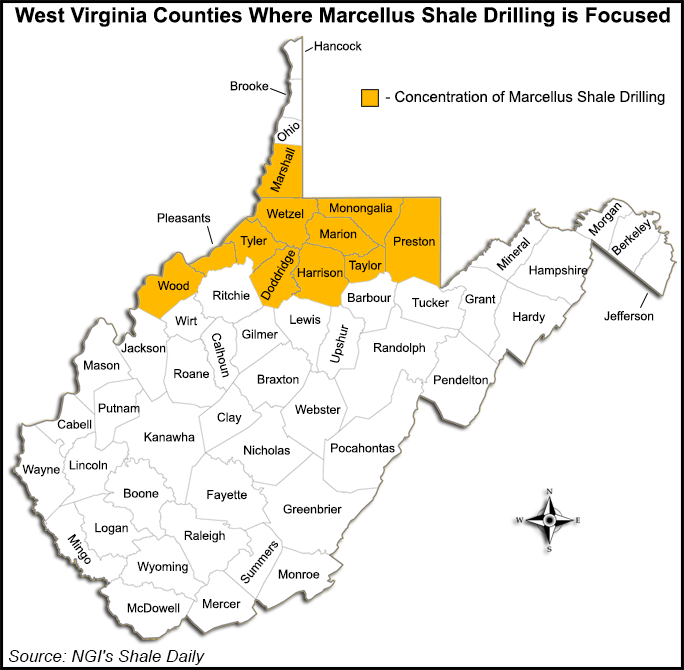

Horizontal drilling continues at a steady pace in West Virginia, where operators are concentrating on a wet gas zone in the Marcellus formation, located in the north-central part of the state and reaching into its panhandle.

Although the state’s first horizontal well was drilled in 2008 and West Virginia’s oil and gas industry dates back to 1859, when oil was first discovered in Wirt County, much of the focus in the Appalachian Basin has been on the excitement surrounding the promise of the Utica Shale in Ohio and the prolific gas fields of Pennsylvania.

Natural gas production in the Marcellus continues to surge, with 12.9 Bcf/d expected to come out of the play in December, or a 3.3% increase from the 12.5 Bcf/d projected for November, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) Drilling Productivity Report released this month (see Shale Daily,Nov. 13).

Included in that tally are wells producing in West Virginia, often considered the southern Marcellus. The counties of Doddridge, Harrison, Wetzel, Marshall and Tyler, among others, have consistently averaged between 24 to 32 rigs since late 2009, said Corky DeMarco, executive director of the West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association.

The figure hasn’t flagged this month either, with Baker Hughes reporting that the state has averaged 33 rigs throughout November, with 37 up and running this week. That’s ahead of 34 rigs in Ohio this week, and behind Pennsylvania’s 54.

What sets West Virginia aside, sources say, is its geography. Both the Utica and Marcellus formations overlap and encompass a broad area that runs almost entirely under the whole state.

“As far as development in the Utica is concerned, [West Virginia] is way behind Ohio. The Utica is so much deeper here,” said Doug Patchen, director of the Oil and Natural Gas Research Consortium at West Virginia University. “The Marcellus is the primary target and for now it amounts to economics; the depth of the Utica is too much to handle.”

The Utica in West Virginia rests about 10,000 feet below the surface, DeMarco said, significantly lower than its starting point of 6,000 feet or so in Ohio.

Exploration and production (E&P) companies also have been satisfied with some of the early production results of the Marcellus in West Virginia. DeMarco said about 15 to 20% of all horizontal production has thus far been natural gas liquids (NGL) that have proved relatively easy to extract because of the state’s geology.

“The reason we’re concentrating drilling in this wet zone area is twofold: you get a bump when you sell these wet hydrocarbons, and the other reason it’s advantageous is because, as far south as Parkersburg, the Marcellus zone is over-pressurized,” DeMarco added. “There’s a limestone floor and the pressure is forcing the gas out in huge volumes.”

In 2011, natural gas production in West Virginia increased by 50%, according to an annual report released earlier this year by EIA.

West Virginia remains one of the nation’s poorest states, with a median household income of just under $40,000. Last year, though, the severance tax on shale gas development generated $90 million.

State records show that West Virginia’s three biggest operators are Chesapeake Energy, EQT Corp. and Antero Resources.

Gordon Pennoyer, Chesapeake spokesman, said he couldn’t divulge the company’s acreage position in West Virginia due to competitive reasons, but he pointed to the company’s steady production in the southern Marcellus, which includes its West Virginia block.

Chesapeake said in its third quarter report that daily net production from the southern wet gas portion of the Marcellus was approximately 275 MMcf/d, up 123% from 3Q2012. The mix included 13% oil, 17% NGLs and 70% natural gas.

In a press release issued with 3Q earnings, Chesapeake CEO Doug Lawler said that although the company will reduce its drilling and completion rates in late 2013, with plans for a lower capital expenditure budget next year, it still anticipates growth that will be lead in part by the Utica and Marcellus shale plays, “which will benefit from new gas processing and takeaway capacity.”

Both Patchen and DeMarco believe shale development is only poised to increase in West Virginia, where pipelines and processing facilities are in demand and remain a concern for E&Ps, just as in Ohio and Pennsylvania.

For more than two years now, DeMarco said, about $1 billion has been spent on infrastructure in the state. Most recently, Odebrecht Organization, a Brazilian company, said it was exploring the possibility of constructing a multibillion dollar ethane cracker and three polyethylene plants in Wood County in northern West Virginia (see Shale Daily, Nov. 14).

“In the established areas of production, it’s been so high that we don’t have the infrastructure to handle it,” Patchen said. “I think obviously the geographic area here is much smaller than it is in Pennsylvania, but most of the prime area is being exploited. I don’t get the sense that we feel that we’re being left behind.”

Bruce Rudoy, co-chairman of the energy and natural resources group at Babst Calland, which practices law in Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania, says shale development in West Virginia is not being overshadowed by its neighbors in the north.

His firm represents about 80 companies active in the Appalachian Basin and he said Babst Calland is doing just as much work on titles, mineral rights and other litigation there as it is in Ohio.

Other companies have plans for the liquids-rich part of the state, as well.

Nick Deluliis, president of Pennsylvania-based Consol Energy, said at the recent DUG East Conference that his company has plans for 75 wells in West Virginia.

Asked if operators will also eventually target the Utica in West Virginia, where only one or two wells have been drilled to date, Patchen said historical data suggests that they will.

“If you look at the history of drilling in the basin as a whole, we’ve put together a development vs. time graph, and historically, operators just keep stepping down,” he said. “Right now, though, there’s just so many well locations here that can be drilled into the Marcellus. So, it will be awhile before anyone really develops the Utica here.”

According to the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection’s Office of Oil and Gas, 1,030 horizontal permits have been issued in the state since shale drilling got under way in 2008.

“We’re just getting started, this is a 50 year play,” DeMarco said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |