Go Beyond What’s Required, Urges Top Colorado Energy Regulator

Colorado’s top oil and natural gas regulator told executives in Denver Tuesday that adopting a culture in the onshore that goes above and beyond what’s legally required will do more than anything to achieve community acceptance.

“If you want to be accepted and just not authorized, you need to go above and beyond what the law requires… That is fundamental,” said Mike King, executive director of the Colorado Department of Natural Resources (DNR). He spoke as part of an afternoon panel at the 25th Annual Rocky Mountain Energy Summit, sponsored by the Colorado Oil & Gas Association.

Several counties and municipalities in Colorado have enacted or are considering putting limits or a moratorium on drilling on this November’s ballots. On Monday, Boulder and Fort Collins officials advanced drilling moratoriums.

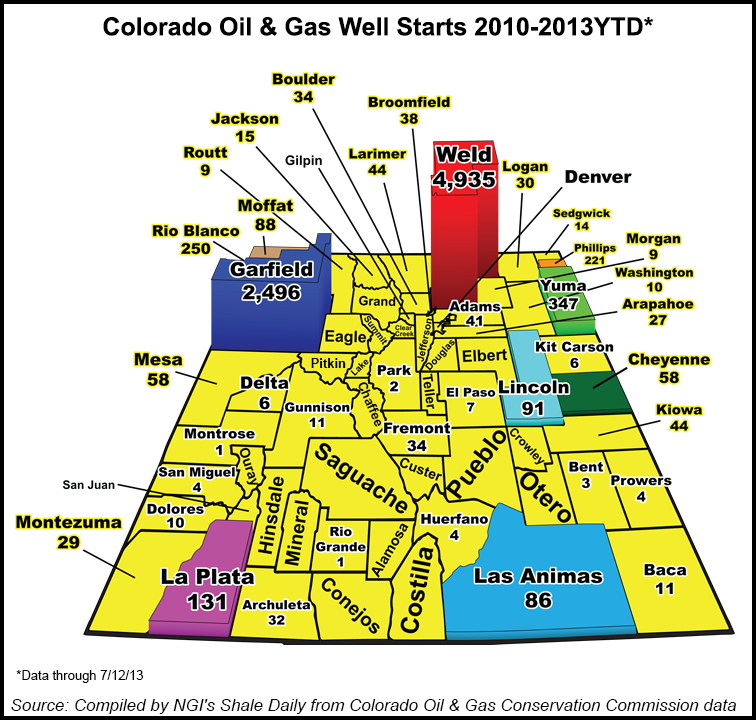

The most active Colorado county measured by well starts from 2010-2013 year-to-date is Weld with 4,935, of which 607 are attributable to 2013, according to data from the Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission (see chart). Rounding out the top five most active Colorado counties over this period of time are Garfield with 2,496, Yuma with 347, Rio Blanco with 250 and Phillips with 221. Boulder County is well down the list with 34 well starts from 2010-2013 year-to-date, with zero starts in 2013.

Many in Colorado have been told that the state’s water supplies are being damaged by oil and gas drilling, said King. Many think water is good but oil and gas are bad. The “bad” message is being heard without an adequate industry or regulatory outreach, especially in newly developed areas.

“We have acute impacts in multiple counties that haven’t dealt with it before,” King said. The industry and regulators have “not doing a good job of explaining the benefits.”

Colorado’s energy industry has had a lot of “successes” in the past. Communities that in the 1990s had prohibited developing wells within their city limits now have as many as 500 wells. Those communities wouldn’t want the industry or the benefits it brings to disappear, said King.

Activism in Colorado is a random affair, however. Some areas of the state embrace all that oil and gas brings to them. Others want it to disappear tomorrow.

Producers, said King, have to engage at the “retail level” and engage stakeholders community by community to ensure projects are transparent and will be safely managed.

What’s not particularly helpful, said the DNR chief, are industry-paid advertisements touting the benefits of the business.

“I’m not sure it helps you in some areas,” such as Colorado’s Loveland or Bolder communities, where the animosity “is so intense. You think you can influence them at this macro level,” but that doesn’t seem to be working.

In places where industry representatives have engaged from the bottom up that practice works well, as evidenced by the embrace given to producers operating in the Front Range. There, community representatives brought all relevant stakeholders into the fold, explained what they wanted to do and responded to every issue that was on the table. In places like the Front Range, stakeholders “feel that they’re not being spun,” King said.

“We still have individuals who want to work through the problems,” but that’s not universal. DNR wants to do what it can to help the oil and gas industry successfully participate. “We look forward to standing shoulder to shoulder…It’s critical to the nation’s economy.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |