NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Mexico Shale’s Future Tied to Proposal on Private Energy Investment

The bullish shale gas potential that has remained largely unexploited among Mexico’s rich hydrocarbon resources could be unleashed if Monday’s proposal by President Enrique Pena Nieto to open the nation to more shared private-sector energy investment ever becomes a reality.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) projected that more than half of the world’s non-U.S. shale gas resources are concentrated in Mexico and four other countries — China, Argentina, Algeria, and Canada (see NGI, June 17). EIA placed Mexico’s shale gas reserves fourth in the global rankings, approaching 681 Tcf of recoverable resources.

“There is still uncertainty about the shale in Mexico, but the best information we have at the moment is that it could be a huge opportunity,” Houston-based Rice University energy economist Ken Medlock told NGI‘s Shale Daily on Tuesday. “We will know more about the potential scale if and when actual development occurs. The Mexican energy sector in general needs more private-sector participation for full realization of its potential.”

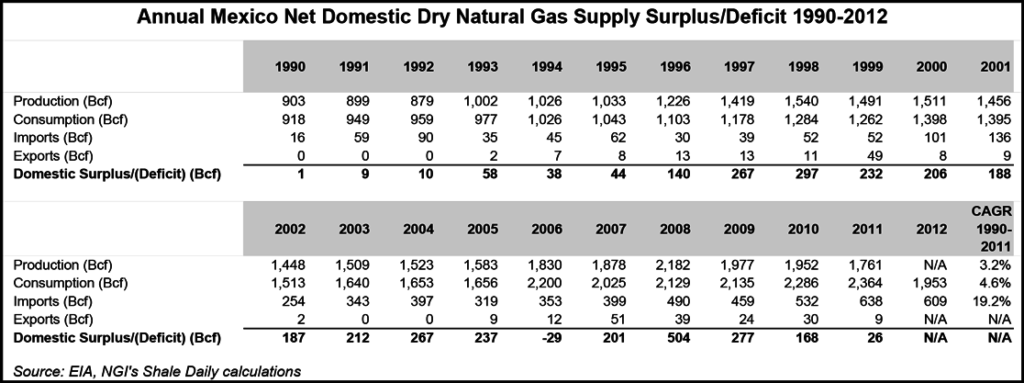

Tapping the country’s 681 Tcf of recoverable shale gas reserves is becoming more of a pressing need for Mexico with each passing year as the nation’s supply/demand equation approaches a breaking point. The country’s imports of natural gas from the United States are increasing at an alarming rate as domestic production increases are failing to keep up with consumption growth, according to Energy Information Administration data and NGI‘s Shale Daily calculations.

In the 22 years from 1990 through 2011, Mexico’s imports of natural gas have jumped nearly 40-fold from 16 Bcf in 1990 to 638 Bcf in 2011. During that same time period, the country’s gas production climbed 95% from 903 Bcf to 1,761 Bcf, while consumption jumped 158% from 918 Bcf to 2,364 Bcf as gas-fired power generation took off.

As reported nearly two years ago, among Mexico’s energy officials there has been agreement about shale gas having potential, but there also has been continuing debate in the federal government regarding whether the nation should focus on finding out exactly what that potential might be (see Shale Daily, Sept. 13, 2011).

In 2011, a relatively new Mexican government body, the National Commission for Hydrocarbons, began pushing other parts of the federal government to pursue a more diversified energy strategy. This came at the end of President Felipe Calderon’s six-year administration. Pena Nieto is still in his first eight months on the job.

While Pena Nieto’s two most recent predecessors tried unsuccessfully to reform Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), the state-owned oil/gas company, the newest Mexican leader took strides on Monday, but stopped short of proposing to allow private energy companies drilling in his country to own and market the oil they produce.

But he did propose constitutional changes that would allow for what were described as a risk- and profit-sharing partnership between foreign firms and Pemex. Energy observers see the move as an attempt to attract the capital and technology Mexico needs to more fully capture the benefits of its challenging deepwater Gulf of Mexico (GOM) resources and shale oilfields, which are viewed as equally difficult to produce.

In recent years, Rice’s Medlock of the Baker Institute of Public Policy, has confirmed that the robust Eagle Ford Shale play in South Texas extends into two of Mexico’s major oil and gas basins. Nevertheless, there has been little activity on the Mexican side of the play. Medlock has said it is well established that the Eagle Ford geology extends well south of the U.S. border.

“Firms have the option of investing in acreage positions north of the border, so the terms [in Mexico] will have to be favorable in order to generate interest,” Medlock said. “Capital will flow to the ventures with the best perceived returns, and an inability to book reserves is a long-standing problem in this regard in Mexico. Of course, this stems from the politics of energy in Mexico, which negatively tilts the economic viability of opportunities there relative to opportunities in other parts of the world, particularly the US.”

In support of this view, a Wood Mackenzie manager of global unconventional gas, Robert Clarke, last year said there had been a little activity on shale in northern Mexico, but not much positive had come out of the exploration (see Shale Daily, July 6, 2012).

The move by the new Mexican president comes at a time when activity between U.S. and Canadian oil/gas companies and Mexican energy officials has never been higher, particularly in the areas of building natural gas infrastructure and exports, along with looking at deep-lying offshore GOM resources (see Shale Daily, March 15).

Exports of U.S. gas to Mexico set a record last year, according to the EIA, growing by 24% to 1.69 Bcf/d. Imports now account for more than 30% of Mexico’s gas supply, and the country’s gas usage is at its highest level ever, EIA said.

In the past year, studies have examined the potential for North America to become a global energy leader, and much of the analysis has focused on the need for Mexico to open its energy markets.

Weary of left-leaning elected officials in Mexico’s Congress and elsewhere who are ready to keep Pemex a state-owned enterprise at all costs, Pena Nieto did not give any details of how his proposed Pemex-private sector partnerships would develop, but he did make it clear that the state-run oil/gas operations would not be “sold or privatized.”

Within Mexico the political road to winning the constitutional amendment outlined by Pena Nieto looks very difficult, although initial assessments indicate that both houses of Mexico’s Congress are expected to pass the measure. The difficulty grows considerably after that in seeking to get at least 17 of 32 state and federal district legislatures to ratify the change.

Jump-starting Mexico’s economy is an obvious driver behind the proposal, U.S. news organizations have been reporting. Mexican officials indicated demand for energy in the country is growing so fast that Mexico could turn from an energy exporter to an energy importer by 2020, according to a New York Times report on the Mexican president’s speech Monday to a carefully selected audience in Los Pinos, the Mexican White House.

Mexico now imports almost half of its gasoline, mostly from the United States. Mexican companies pay 25% more for electricity than competitors in other countries, the government has calculated. Although Mexico potentially has some of the world’s largest reserves of shale gas, it imports about one-third of its natural gas and is making moves to increase the imports substantially.

Reports out of Mexico City cited recent public opinion polls in Mexico that indicate up to 65% of the population is against the proposed constitutional changes, and Mexican political analysts compare Mexicans’ attachment to Pemex to Americans’ love of apple pie.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |