NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Harvard Researcher Sees U.S. as Largest Oil Producer by 2017

The United States could produce 5 million b/d from shale oil deposits by 2017 and may become the world’s largest oil producer — reaching up to 16 million b/d in just a few years by combining shale with conventional oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG) and biofuels, according to a researcher at Harvard Kennedy School.

Leonardo Maugeri, a former senior executive at Italy’s Eni SpA, said that after studying more than 4,000 shale wells, as wells as the activities of 100 oil companies devoted to shale oil production, the United States could become the world’s largest oil producer “in just a few years.” His findings were in a discussion paper, “The Shale Oil Boom: A U.S. Phenomenon,” which was published in June by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

“The large resource size — and the ability of the industry to develop it through steady improvements in technology and cost — may dwarf earlier forecasts,” Maugeri said. “The largest U.S. shale oil formations seem capable of sustaining increased production, with a total capability of more than 100,000 producing wells versus around 10,000 of actual producing wells today.

“Improvements in knowledge of geology and drilling technology may prolong the productivity of shale formations well after 2030.”

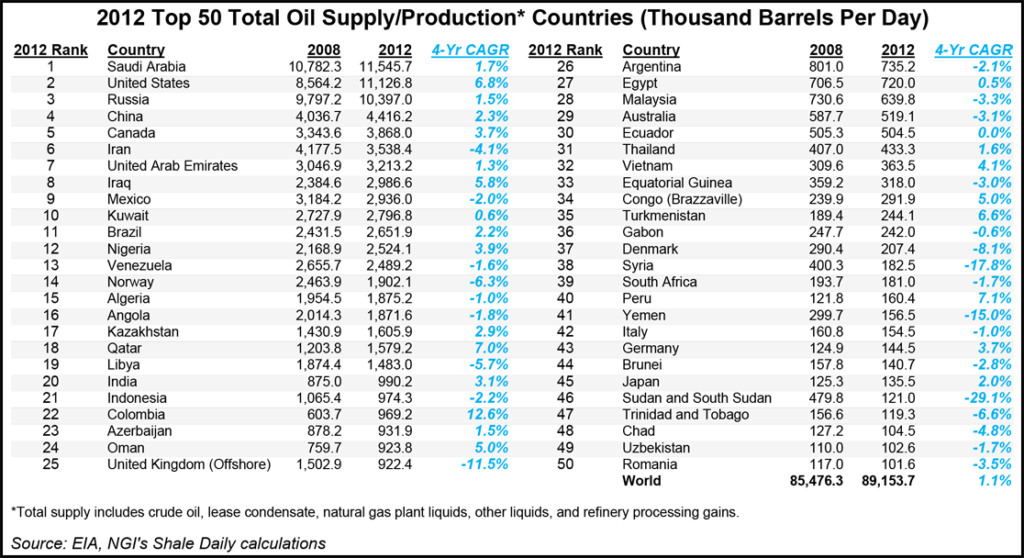

In 2012, the United States ranked second in the world in terms of total oil supply, producing 11.127 million b/d, just 419,000 b/d behind Saudi Arabia, according to Energy Information Administration (EIA) data and NGI’s Shale Daily calculations. Moreover, the United States is one of fastest growing total oil suppliers in the world, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 6.8% between 2008-2012, versus just 1.1% for the world as a whole. Only Colombia (12.6%), Peru (7.1%) and Qatar (7.0%) have grown at a faster rate than the United States since 2008.

The EIA includes crude oil, lease condensate, natural gas plant liquids, other liquids and refinery processing gains in its measurement of total oil supply.

Maugeri said the United States was in a unique position to develop its shale oil resources, since it controls more than 60% of the world’s availability of drilling rigs. He added that 95% of the drilling rigs can perform hydraulic fracturing (fracking).

“No other country or area of the world has even a fraction of this drilling capacity and building up this power would require several years,” Maugeri said. “There are other factors that will make the global replication of a U.S. style shale boom difficult, including [a] lack of private mineral rights in most countries, as well as the absence of the U.S. independent companies whose guerrilla-style operational mindset has proven essential to the exploitation of shale formations that, unlike conventional oil and gas fields, require companies to move on a micro-scale, on multiple micro-objectives, and flexibly leverage short-term opportunities.

“The combination of vast geologic supply of shale oil and low population density in these areas allows for intense, sustained production unique to the United States.”

Maugeri said maintaining the shale oil boom in the U.S. would be hard because it would require bringing as many wells online as possible — an especially difficult proposition in densely populated areas — because of the steep decline in production that follows the early months of a new well.

To illustrate that point, Maugeri said in December 2012, operators had to bring 90 new producing wells online every month just to maintain the Bakken Shale/Three Forks Formation oil production rate of 770,000 b/d. “This drilling intensity will most likely be sensitive to a sudden dip in oil prices, resulting in a rapid downward shift in U.S. shale oil production.”

Maugeri added that production would be price sensitive, and if the price of oil fell from $85/bbl in 2013 to $65/bbl in 2017, the United States could produce about 5 million b/d of shale oil by 2017, with more than 90% from the Bakken/Three Forks, Eagle Ford Shale and the Permian Basin.

“It is comparatively easy to stop shale oil production as opposed to conventional oil, especially offshore,” Maugeri said. “Conventional oil production requires a high upfront cost and wells have a long production life (30 years). Shale oil is quick and relatively cheap to start up and has continual costs and a short production life (one year). New wells come online all the time and can be brought offline if the price of oil falls.”

Despite the shale oil boom, Maugeri said the United States would still import some of its oil from the Middle East.

“The U.S. shale oil boom may have paradoxical consequences in terms of U.S. energy security by endangering traditionally safe sources of U.S. oil imports such as Canada and Venezuela,” Maugeri said. “It will also affect the oil production of several African countries — Nigeria, Angola, Libya, Algeria — that, in turn, will have to find room for their production in other export markets.

“This will create additional strains within the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), whose ability to manage an oil production capacity that is growing much faster than demand will rely almost exclusively on the will of Saudi Arabia to increase its unused production capacity.”

Maugeri added that international sanctions against Iran, enacted to punish the country for its clandestine nuclear program, have crippled its ability to export a significant part of its oil. He said the sanctions “are easing a situation that would otherwise create the conditions for a short-term drop in oil prices.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |