NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Shale Gas Boom Creating Challenges for State Regulators

State regulators continue to be the primary overseers of shale natural gas development, but because of the speed at which the boom shifted — and continues to shift — the energy marketplace, the dynamic environment has created challenges for the energy industry and all of the stakeholders involved, according to a report by Resources for the Future (RFF).

Figuring out who’s doing what where proved to be a monumental task, said RFF’s Alan Krupnick, who directs the Center for Energy Economics and Policy. He and his team shared their insights during a webcast on Thursday.

“What may now be obvious, is that this shale gas development is having a profound effect on the energy market and host of energy policies at the state and federal level,” Krupnick said. “It’s remarkable. It was not predicted by the energy market folks, the government…” The ability to produce huge amounts of gas from unconventional formations as quickly as has been done “caught nearly everybody by surprise.”

Those surprises have been well detailed by federal and independent energy analysts. However, what’s not been clear is how much of an effect the surge in drilling has had on a state level.

“It’s having an overwhelming effect if you are an investor,” said Krupnick. “Clearly, shale gas is shaping how coal will be utilized now and in the future in the electricity markets; it’s shaping the future of nuclear energy. It’s having an impact on industrial development in the country and indeed, especially as a feedstock in the chemical industry. It’s impact on pushing out into the transportation sector is growing, although it is un an unclear path at this point…

“But it’s also shaking up a host of federal and state policies…Basically, those policies initially were designed to assume declining, if not flat — supplies of natural gas at very high costs. As you know, as late as 2007, when Congress passed the last comprehensive Energy Act, it was still presumed that we would be pursuing liquefied natural gas to supplement the gas market domestically.”

Playing catchup hasn’t been easy, as RFF’s researchers discovered. They spent a year and a half combing through state shale gas-related legislation and permitting requirements to try and put a fix on what’s happening. However, unlike some other types of studies, RFF wanted to do it from a social science perspective, where there’s not a lot of research, Krupnick said.

The final product, “The State of the State Shale Gas Regulation,” parsed and compared 25 regulatory elements related to shale gas development across 31 states — considered a first such attempt by anyone. However, it’s a living document; the regulatory environment is evolving so quickly that RFF expects to continue to update its findings.

The report details what type of regulatory tools each state uses, how many regulations a state has relative to other states, and for some regulations, how stringent they are.

In the number of regulations and the stringency of regulations, economists “found a high degree of heterogeneity among states,” said Nathan Richardson, who co-authored the report with Krupnick, Madeline Gottlieb and Hannah Wiseman.

“The report also highlights a lack of transparency in state shale gas regulations,” Richardson said. “Though regulations are publicly available, they are often difficult to find and interpret, even for experts. Moreover, states’ use of case-by-case permitting makes it challenging for researchers and the public to determine what is regulated and required.”

State regulators and stakeholders often ask how to implement the “best” shale gas rules or how to improve the ones they have in place, Richardson said. The RFF report attempts to answer both questions.

“However, we only analyzed what some current regulations require, not their costs and benefits or how they are enforced. We also did not rank the overall quality or effectiveness of each state’s regulations” because a state could impose stringent permitting requirements, but if they are not enforced, then their effectiveness is moot.

The 25 elements tracked by economists included general well spacing, building setback, water setback, predrilling water well testing, casing/cementing depth, cement-type production, surface casing cement circulation, intermediate casing cement circulation and production cashing cement circulation.

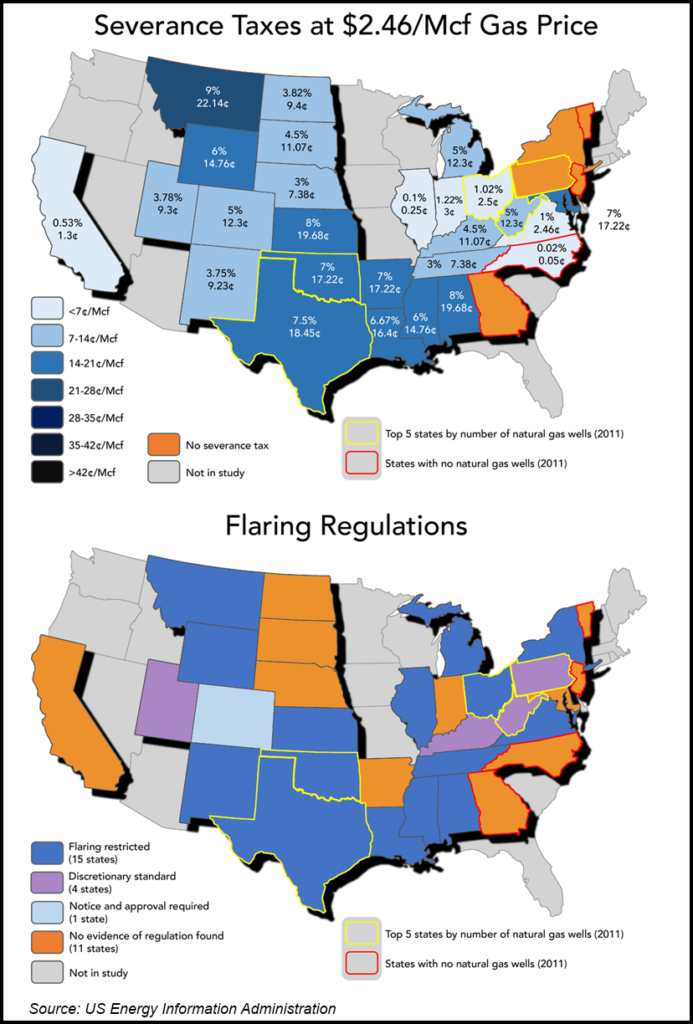

Also tracked across the 31 states were requirements for water withdrawals, hydraulic fracturing fluid disclosure, fluid storage options, freeboard, pit liners, underground injection, fluid disposal options, wastewater transport tracking, venting, flaring, severance taxes, well idle time limits, temporary well abandonment, accident reporting, bans/moratoria, and regulatory agencies.

“We statistically tracked 20 of the 25 regulatory elements,” Richardson said. Five elements — general well spacing, fluid disposal options, severance taxes, bans/moratoria and regulatory agencies could not be “cleanly” compared in the report.

“We found that states regulate anywhere from all 20 elements,” including West Virginia and under its proposed regulatory package, New York, “to only 10 elements, such as California and Virginia.”

The five states with the most gas wells — Texas, Oklahoma, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia — regulate at least 16 elements, more than the national average of 15.6.

“Differing conditions among states may justify regulating more or less stringently,” or not regulating an element at all, Richardson said. However, RFF also explored the possible relationships between several state characteristics and the regulatory activity ongoing.

“The heterogeneity of shale gas regulations is pervasive,” he said. “It can be seen in what states regulate and how stringently they do so…Of course, similar heterogeneity exists in many types of state regulations — from income and sales taxes to speed limits. Regulatory differences may reflect underlying differences of geology, hydrology, demographics or other factors that affect the local risks of shale gas development — or they could be a result of random variation built up over decades of changing oil and gas regulation, or even political factors.”

Economists analyzed the associations between observed regulatory agencies and more than 50 other variables, such as environmental, demographic and political. The analysis unveiled “several significant associations,” said Richardson.

“For example, states with more gas wells tend to regulate more elements, perhaps reflecting a greater need for regulation where there is a larger industry presence. Also, regulations that protect groundwater,” such as underground aquifers, “tend to be more stringent in states where groundwater makes up a greater fraction of overall water consumption.”

Heterogeneity alone “is not a bad thing, and it is not necessarily surprising,” said Richardson. “But whether it is justified — in an economic and environmental sense — depends on whether it is rooted in underlying differences among states that affect the costs and benefits of policy choices,” such as differences in hydrology, geology, and demographics.

“That remains unclear; the preliminary analysis in the report cannot, alone, determine whether heterogeneity is justified. But we found only a few relationships between the heterogeneity we observe and what to us seem to be among the most obvious underlying differences that could drive it.

“More research is needed, and we look forward to making further contributions. We hope our results will induce those who say the heterogeneity of shale gas rules is justified by relevant underlying factors to better support their position. More broadly, we hope our analysis will inspire dialogue among states and critical examination of why regulations are what they are today and whether they can be improved — to better protect the public, to reduce compliance costs, to better fit local conditions, to keep pace with technology and to reflect the best thinking about regulatory design.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |