NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

West Virginia Enviro Groups Ask USDA to Require Tracers

A coalition of nine environmental groups in West Virginia have asked the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to require that operators add tracers to fluids used in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) at Marcellus Shale oil and gas wells drilled near the Monongahela National Forest.

The nine groups specifically want the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), an agency of the USDA, to amend Chapter 2820 of the Forest Service Manual by adding a tracer requirement. The chapter in question is titled “Mineral Leases, Permits and Licenses.”

“An effective tracer rule should establish tracer standards instead of prescribing particular technologies or methods,” the groups said in a joint letter on Feb. 28 to Harris Sherman, the USDA’s Undersecretary for Natural Resources and Environment. “Standards should ensure that tracers are identifiable to a particular well, non-toxic, detectable at small concentrations, and mobile through a wide variety of geomorphic and hydrologic conditions.

“We recommend that tracer requirements be implemented at the time of surface occupancy permit approval for both leased and split-estate drilling. We also recommend that the tracer rule be promulgated through a formal rule-making process with appropriate compliance with NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] to ensure that the environmental effects of tracer options are disclosed at an early stage.”

Beth Little, membership secretary for the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, one of the groups that signed the USDA letter, told NGI’s Shale Daily that lawmakers in the West Virginia Legislature had debated a tracer requirement but have not enacted one.

“We’re really concerned about the water,” Little said Monday. “Tracers have been mentioned here before. The natural forest serves as the headwaters for a lot of places. The industry keeps saying ‘it’s not us,’ ‘[fracking] is completely safe,’ and so forth. Tracers just really seem like a way to prove what’s going on, where we can’t see what’s going on.”

The other signatories to the letter were the West Virginia chapter of the Sierra Club; Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics; Eight Rivers Council; Greenbrier Watershed Association; Allegheny Highlands Alliance; Friends of Beautiful Pendleton County; Allegheny Front Alliance, and the Elk Headwaters Watershed Association.

West Virginia Oil and Natural Gas Association Executive Director Corky DeMarco told NGI’s Shale Daily that the organization recommended drinking water samples near drilling sites be tested before any drilling is performed, and then tested again if there are any problems. He said oil and gas companies could be required to provide fresh water to residents if their well is contaminated, at least until a new water well is drilled or remediation efforts are successfully concluded.

Asked if he thought oil and gas companies would support a tracer requirement, DeMarco said, “I would assume so. We try to be as transparent as possible.

“If it’s not an undue burden, [the operators] wouldn’t have any problem with it. But if it’s going to cost another $100,000 or some other outrageous amount like that, people might bow up on you. But I don’t know that we have any problem with doing water samples, and then to have those requirements in their code.”

The Monongahela National Forest was formed in 1911 and comprises more than 921,000 acres across nine West Virginia counties: Grant, Greenbrier, Nicholas, Pendleton, Pocahontas, Preston, Randolph, Tucker and Webster.

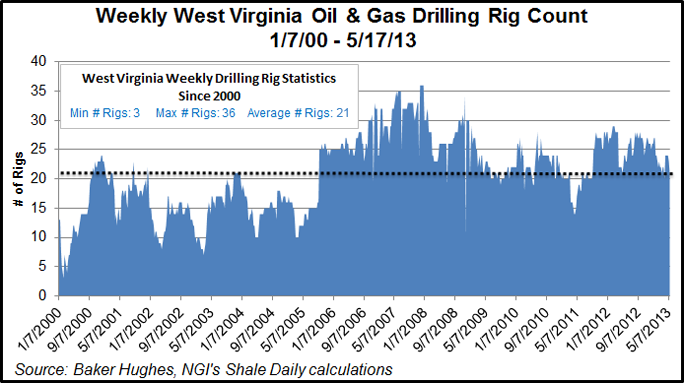

The number of drilling rigs operating in West Virginia, which peaked at 36 in late 2007, was as high as 28 in September 2012, but declined to 21 by May 17, according to Baker Hughes data.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |