NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

Shale Market Approaching ‘Guillotine Moment’

The torrent of natural gas production coming out of North America’s shale plays reminds Jim Duncan, chief analyst and commodity market strategist at ConocoPhillips Gas & Power, of the opening lines of “A Tale of Two Cities,” Charles Dickens’ epic novel of the French Revolution.

“It is really a tale of two markets. Depending on who you talk to, it is the best of times — or the not-so-best of times,” Duncan said Tuesday at the LDC Gas Forum Southeast in Atlanta. Things are going very well for end-users of natural gas, but not so well for producers, thanks to a tsunami of natural gas coming out of unconventional plays and the resulting downward pressure on gas prices.

And, like Dickens’ hero, Charles Darnay, someone must “take one for the team.” But what is the industry’s “guillotine moment”?

“Most everybody has been focusing on the supply side of this, of course…[but] it’s that thing that doesn’t seem as obvious — it’s the demand side. It is a fact that natural gas prices have been so low for so long that people in the world have taken notice. And I will tell you that over the next several months, you’re going to see an increasing list of new demand sources for natural gas. And that’s the Darnay moment for us.”

Over the past two decades, data shows that nine to 12 months after prices bottom out, the impact will show up in the supply market, Duncan said.

“We saw that in 2002…That year we were 4 Bcf/d oversupplied, by general collective reasoning from everybody that you talked to; 4 Bcf/d in any market for natural gas is well supplied and downside pressure on the market. And as late as last June those same equations put out that we were 1.8 Bcf/d oversupplied. And then most recently those same equations put out that we were 1.4 Bcf/d oversupplied. Anybody see a trend yet?

“Because this market becomes very unstable when it becomes under supplied. And theoretically, that may be where we’re headed.”

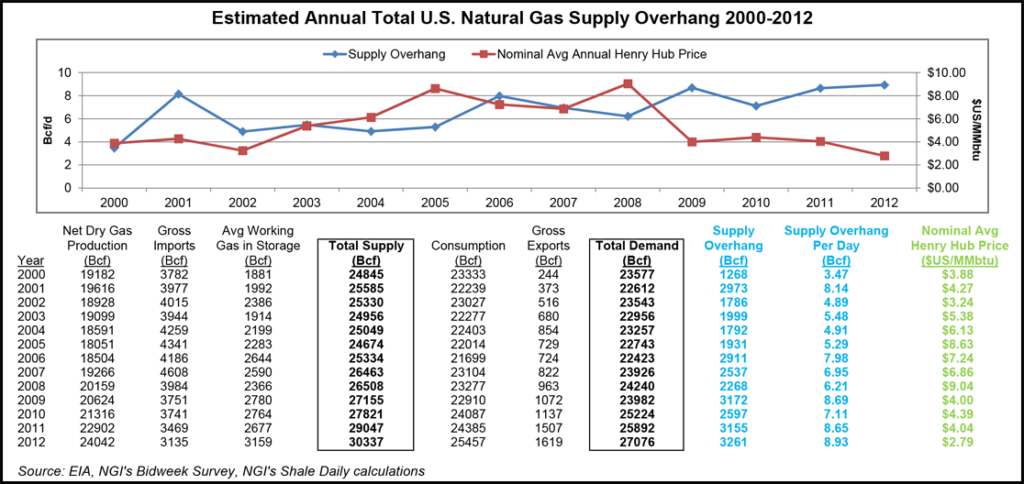

But those overall supply figures may not fully take into account storage levels, which could have a dramatic impact on the true supply picture in the United States. According to NGI calculations from Energy Information Administration data, the overall supply overhang in the U.S. has been trending higher since 2000, so much so that excess supply in the U.S. has grown from 3.5 Bcf/d in 2002 to nearly 9 Bcf/d in 2012. The average amount of working gas in storage soared last year, rising from 2,677 Bcf in 2011 to 3,159 Bcf in 2012.

Working gas levels have fallen significantly in recent weeks, however, and stood at 1,704 Bcf for the week ended April 12, a full 73 Bcf lower than the previous five-year average. NGI recently calculated that the amount of excess gas in U.S. storage facilities versus the previous five-year average has shown a high 89.7% R-square statistic to changes in Henry Hub prices over the last two years, and that relationship may point to higher prices, at least in the short term (see Shale Daily, April 11).

Sustained higher U.S. natural gas prices in the long term will likely require a secular reversal in the growing annual supply overhang, however, and that could be accomplished by some combination of slower supply and faster demand growth.

Eventually, liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports will add to demand, Duncan said. “I look at [LNG exports] more like a safety valve on a market that needs some sort of sophisticated type of controls in terms of supply and demand. Otherwise we end up with a market that goes through shocks because nobody’s looking for them.”

It wasn’t so long ago that the industry was scrambling to build facilities to import LNG from overseas. “And then something little happened called shale, and it messed that whole thing up,” Duncan said.

But the positive fallout of the shale gale — abundant domestic natural gas, lower prices for consumers, a surge of manufacturing and industrial facilities switching to the lower-priced fuel — has only just begun. The plays that led the way during shale’s recent days — the Eagle Ford, the Marcellus — are going to get plenty of competition from the rising class — the Utica and the Niobrara — Duncan said.

“This is the year when the Utica starts showing up…the Utica is becoming more important to the overall Northeast supply picture, and we know that the Northeast has a chance to become energy neutral in terms of supply and demand within a very short period of time,” he said. And 2013 “is going to be a breakout year, probably, for the Niobrara.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |