E&P ‘Specialists’ Finding Value in Smaller Focus, but For How Long?

Oil and natural gas production specialization, i.e. focusing on one area or play, is enabling operators in North America’s onshore to achieve more efficiencies and improve financial results, but the strategy over the longer term could in fact create significant risk from market volatility.

Those findings are included in an analysis issued Thursday by business information provider IHS Markit. The narrow corporate strategy may prove to be a positive in many ways, but some exploration and production (E&P) companies face risks from volatility, fragility and vulnerability to unforeseen events.

“Specialization is increasingly driving strategic focus for oil and gas operators because, for a time, it works, and the market prefers and rewards specialists,” said IHS Markit’s Raoul LeBlanc, vice president of financial services and lead author of “The Promise and Peril of Specialization.”

“When you focus on one play type or asset, like an athlete who focuses on a single sport, you tend to get better at it and become faster and more efficient.”

Investment banks and many investors have pushed for the narrower focus, “and while there is certainly great upside to this approach, there are also new risks that may not be readily apparent.”

Having bigger operations traditionally has been central to the oil and gas industry. Many operators have worked globally, facing “a nearly unparalleled array of political, financial and technical risks,” researchers noted. “Scale and diversity, it was argued, was the best buffer against these risks.”

However, the “bigger is better” mantra has been supplanted by the turn toward specialization, which emerged as unconventional drilling took hold.

The narrow focus gained momentum as tight resources and shale were successfully tapped, which turned to more spending in fewer areas. The gains in the onshore also exposed the frequent “poorer risk-reward ratio” for many international investments.

“Two new developments accelerated the trend toward onshore specialization,” LeBlanc said. “First, shale production has grown large enough to generate significant cash flows, allowing companies to sell the ”distraction’ of other asset types, which virtually every large E&P player has done in their North American portfolio.”

Companies now specialize in particular areas that include unconventional, offshore and/or carbon dioxide plays. Only the Big Oil majors are integrated, and many large-cap and small-cap E&Ps have reduced their portfolios to work in only one or two areas.

“Secondly, the maturation of major shale plays beyond the delineation phase has reduced risk by revealing the overall quality of acreage holdings,” according to researchers. “As the industry moved into the low-risk, high-capital phase of the plays at the same time cash flows collapsed post-2014, companies focused on their best assets.”

”Hypercompetitive Environment’ Encouraging Specialization

Operators that formerly strived for “breadth in technologies and geography” now tend to compete in narrow, competitive bands “in pursuit of a deeper, more limited, set of skills.”

Global producers increasingly are focused on specific countries or regions, with many shifting from international activities to less risky U.S. and Canadian onshore activity. Within North America, the “hypercompetitive environment” has pushed some E&Ps toward specializing on one play only, thus becoming pure-plays.

“Within the U.S. upstream segment, the transition from conventional to unconventionals has been profound,” LeBlanc said. “At the dawn of the tight-rock era, virtually all companies in the U.S. held portfolios characterized by conventional oil and gas holdings in multiple regions, plus some near-field exploration opportunities. As the potential of shale became apparent, they shifted capital deployment toward those assets, retaining conventional assets as cash generators to fund early stage positions.”

The biggest U.S.-based independents — which include Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Apache Corp., Encana Corp., Devon Energy Corp., EOG Resources Inc. and Pioneer Natural Resources Co. — have established significant footholds in specific onshore plays. These long-time operators understand “that some plays fail and that despite best efforts, their acreage might not be in the sweet spot of well quality,” researchers noted. “Diversification among the various plays hedged those risks.”

Big Oil majors, including BP plc, Chevron Corp. and ExxonMobil Corp., also are becoming more specialized despite their integration and are in fact redirecting significant capital to the U.S. onshore, particularly the Permian Basin, IHS Markit noted.

Integration Adds Endurance

“Like decathletes, major companies possessed a breathtaking range of skills and endurance, but as more specialists dig down on particular technologies and geographies, the decathletes are finding it hard to compete,” LeBlanc said. “This has been particularly evident in the majors’ struggle to compete with shale specialists at their own game.”

However, specialization narrows the long-term horizons for an operator, IHS Markit said.

“Building an operation around developing a single or narrow portfolio of assets, even one as prolific as the Permian, may determine a company’s lifespan.”

Researchers noted that the narrow focus “already been witnessed with companies focusing on older gas plays,” such as the Barnett Shale and Pinedale Anticline, and it has begun to creep into more mature plays like the Bakken Shale, “where investors have grown concerned about the dwindling inventory of core drilling opportunities.”

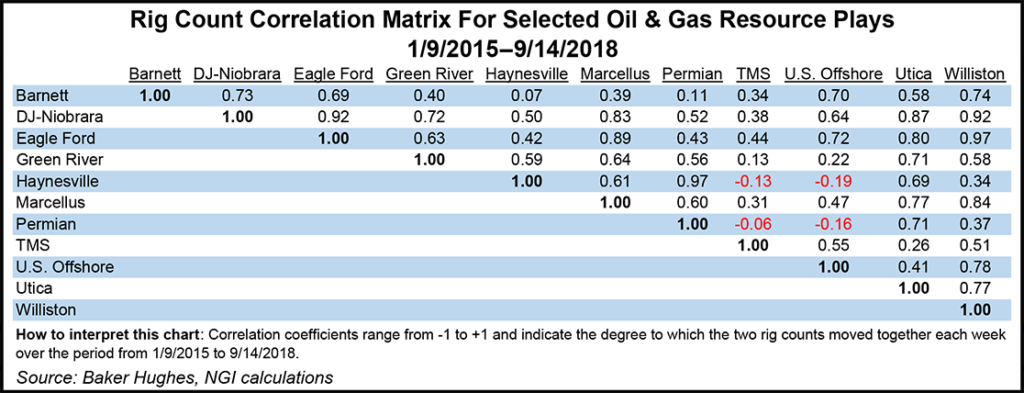

In addition, only a few companies develop within both major unconventional gas and unconventional oil plays.

“There are no major producers with significant positions in both the Marcellus/Utica, the top gas play in the U.S., and the Permian Basin, the top oil play,” LeBlanc said.

Increasingly, companies have evolved into pure-plays to work within one basin or even subsections of a single basin. For example, Pioneer is selling its Eagle Ford Shale portfolio to center development in the Permian.

“The question becomes what happens to those single-play specialists when their play is no longer competitive with other shale basins,” LeBlanc said. Specialization risks sapping an E&P’s ability to explore new frontiers.

“In today’s environment, new ventures investments are a costly distraction from near- and medium-term objectives,” LeBlanc said. “The problem will become apparent over time if the company fails to successfully migrate from its core asset.”

The biggest risk of specialization may be environmental volatility, the report said. Operators with a single focus may be “fragile” and unable to anticipate changes, the kind that corporate giants were built to withstand.

For instance, a sudden public turn against unconventional drilling, similar to the ongoing struggle in Colorado, or a potential ban on deepwater drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, which occurred following the Macondo tragedy, “could spell disaster for a company with no other options in their portfolio outside of their area of specialization.”

In addition, alternative energy supplies may undermine the economics of a single asset. A breakthrough in alternative/renewables technology, or stringent government policy to reduce carbon emissions, “could sap value” from a portfolio if a company were unable to adapt and compete. Investors could abandon an operator that misses a market shift.

Diverging exposures “creates a gaping wedge between management and shareholders in an era of specialists,” according to LeBlanc.

“In the past, investors wanted asset diversification to protect the company’s long-term viability as an investment,” he said. “Today, investors seek diversification through their own investment in many different companies, so are more focused on a company’s short-term financial performance, rather than its long-term viability. That works for the investors, but it may run counter to the company’s long-term best interests…”

The specialization is delivering financial results and it should continue. However, the commodity price downturn that began in mid-2014 and lasted about two years proved that the integrated business model is solid, LeBlanc said.

“As falling prices undercut the profitability of upstream operations, the integrated companies saw their downstream operations pick up the slack, while the more diversified portfolios gave them more options to find attractive investment opportunities,” LeBlanc said.

Every play in the U.S. onshore is in the process of downspacing, according to IHS Markit said. That means that every asset, particularly in small core areas in which some operators specialize, “is finite and will deplete. In the long-term, companies will need to transition to a new asset,” researchers said.

“In addition to exhaustion concerns, specialization in the development phase, which is where most companies are at this point in unconventionals, also makes it difficult for companies to add significant shareholder value,” LeBlanc said. “We see oil and gas companies typically creating the most shareholder wealth by taking chances on unproven rocks and delivering big new reserves in the proving and optimization stages of a play.”

Companies that are using the manufacturing mode to develop onshore wells at the mid-life stage “must invest the bulk of the lifetime capital,” but they have “relatively little value-add from low-risk capital deployment. Opportunities for value creation are especially thin for later entrants that paid an entry premium for premier plays like the Permian,” he said.

Specialization works “until it doesn’t. The industry’s rush to focus is exposing companies to systemic and company-level risks that ”diversification’ previously reduced. Specialists would be wise to consider these hidden risks and develop options to mitigate them.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |