Mexico’s Independent Oil, Gas Producers Operating Under Shadow of Pemex

As Mexico’s historic energy reform approaches its five-year anniversary at the end of 2018, hydrocarbons production by companies independent from the country’s long-dominant national oil company remain in the embryonic stage.

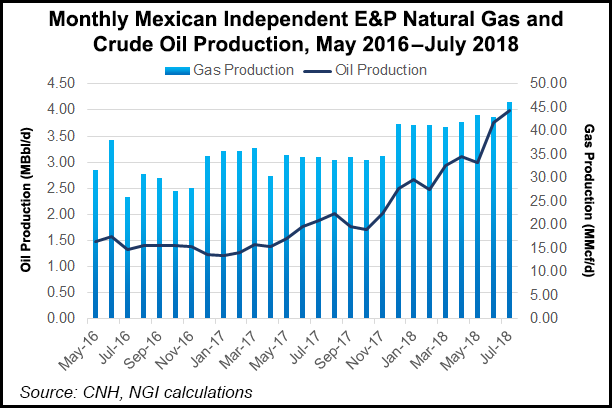

July output at fields not associated with Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) averaged 3,983 b/d of crude and 46 MMcf/d of gas, versus national totals of 1.84 million b/d and 3.63 Bcf/d (excluding nitrogen content), according to the latest figures from upstream regulator Comision Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH).

These figures do not include the international companies that have signed farmout agreements with Pemex to jointly develop blocks, or the pre-reform service contracts that the state company is migrating to the new legal regime.

Since the Mexican Congress approved the reforms in 2013, the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, who leaves office in December, has awarded more than 100 exploration and production (E&P) contracts to private and foreign operators.

Some of these contracts have already yielded discoveries, but few have reached commercial production, as the CNH data show. They also include 21 gas-rich blocks tendered last year at the jointly held 2.2 and 2.3 bidding rounds for onshore acreage.

“Really none of the areas from the gas-focused rounds have begun producing yet,” Pablo Zarate told NGI’s Mexico GPI. He is director of information at Pulso Energetico, a think tank supported by Amexhi, the Mexican private sector association of oil and gas companies. “These are processes that will take some time, although the rounds were quite successful.”

For the Mexican natural gas sector, developing an ecosystem of independent producers has several appeals. For one, it would ease the country’s dependence on imported gas, which currently supplies about 65% of the roughly 7.9 Bcf/d that Mexico consumes.

Reducing that dependence is a policy objective shared by Pena Nieto and the incoming President-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, despite their markedly different views on the energy reform.

The emergence of independent producers also could stimulate the development of Mexico’s wholesale gas market, which was itself liberalized as part of the reform. An emerging base of independent producers could, for example, encourage the formation of local price indexes to compete with U.S. benchmarks that are widely used in the market now.

They could also push the development of Mexican pipeline systems in new directions, and toward new sponsors. Most recent pipeline projects in the country are anchored by transport agreements with federal power company Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) and, to a lesser extent, Pemex, to supply Mexican power plants and industrial consumers with imported gas from basins in the United States.

Moreover, although private developers are building the pipeline infrastructure, CFE and Pemex, as state companies with the full backing of the Mexican government, offer an “implicit sovereign guarantee,” said Houston-based George Baker, editor of Mexico Energy Intelligence.

The result is that the outgrowth of Mexico’s pipeline systems has been largely underpinned by its state energy companies with demand-side considerations in mind. This contrasts with developments in the gas market to the north.

“In the United States, producers become anchor shippers on new pipelines quite frequently,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of strategy and research. “In fact, since the shale revolution really took hold in 2007, the overwhelming majority of new pipeline projects have been underwritten by producers that sign 10-year or longer contracts.

“Mexico is probably many, many moons away from that happening, especially if the country doesn’t allow fracking,” he added. “These independent producers would likely build gathering systems to get to existing pipelines, most likely the national Sistrangas system. But I really doubt we’d see a producer-underwritten pipeline until there is a critical mass of production from these independents.”

Early Gas Producers

The 46 MMcf/d produced during July came from 23 different contracts. More than half of the contracts are located in the northeastern Burgos Basin, Mexico’s largest non-associated production area.

The single largest producing contract at 9.3 MMcf/d is Block 2 in the Burgos, operated by Mexican consortium 5M del Golfo. Most of these early gas producers are local companies, along with some international junior explorers like Renaissance Oil Corp. and Pantera E&P, a

Mexican-Canadian joint venture than won various blocks at the 2017 auctions.

Only one-third of contracts from the gas-focused 2.2 and 2.3 rounds have started to report production, and their output is minimal, according to the CNH data. A majority of the current gas-producing fields were awarded at onshore bidding round 1.3, held in 2015.

The competitive bidding at 2.2 and 2.3 exceeded most analysts’ expectations and indicate there is some investor interest in developing domestic production of natural gas in Mexico, according to Zarate. Mexican gas production, as well as crude output, has been on the decline since the mid-2000s, one of the motivations for opening up the sector to private participation in 2013.

“The number of contracts signed for 2.2 and 2.3 was significant,” Zarate said. “While it’s difficult for a single bidding round to act as a game changer in terms of national production, it can lay the foundations for a recovery in domestic gas output.”

Marketing By Producers

E&Ps in Mexico intending to sell their output must apply for a marketing permit from the Comision Reguladora de Energia (CRE), the midstream and downstream energy regulator. The CRE has currently approved around 30 such permits to commercialize both oil

and gas.

Operators are required to report transactions to the CRE on a quarterly basis. So far, most appear to be offloading their production with third-party oil and gas marketers.

“Based on the information presented by the operators so far, their sales are to other marketers,” a CRE spokesperson told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “However, given the periodicity of the report and the data that has yet to be reported to the CRE, it’s possible that they are doing other types of deals that we are not aware of.”

In early August the CRE revised its open access rules for natural gas pipelines, with the aim of streamlining the open season process and facilitating the development of a secondary capacity market. The revised rules took effect on Tuesday (Aug. 28).

A transparent secondary market would also help send economic signals for pipeline expansions in new regions of Mexico whenever third-party gas production reaches a critical mass.

“We should keep our eye on that star of Venus that one day there’ll be enough gas coming out of the ground in Mexico from private contractors going into private bilateral deals that it will justify building a pipeline based on the reliability of commerce, not on Pemex or CFE as a sovereign guarantor,” Baker said.

AMLO Uncertainties

It is difficult to predict when output by non-Pemex operators will start to influence the Mexican gas market as a whole, but it will largely depend on decisions by the incoming administration, according to Zarate.

Lopez Obrador’s full plan for the energy sector is unclear and will likely remain so at least until after he takes office in December. But his energy team includes fierce critics of the reform who would likely support the continued dominance of Pemex in the upstream sector.

Regulators have already postponed two ongoing E&P rounds and a farmout tender by Pemex to allow the incoming government to review the 100 or so existing contracts, a campaign trail promise by Lopez Obrador, who also goes by the initials AMLO. It is unclear when and if the AMLO administration would hold new bidding rounds after taking office in December.

Lopez Obrador has also vowed to end hydraulic fracturing (fracking) in Mexico. The CNH has estimated that 68% of the country’s gas resource potential lies in unconventional reservoirs, and one of the postponed bidding rounds would be the first to offer up unconventional blocks for private sector development.

On the other hand, AMLO’s energy team is also reportedly evaluating holding bid rounds specifically focused on gas resources to reduce Mexico’s dependence on imports. The other stalled auction heavily features gas-rich conventional blocks.

“If there is the political will to develop Mexico’s shale, if they continue emphasizing gas in the rounds, and if they keep looking for mechanisms to incentivize the development of gas resources in Mexico, then I think we could talk about things starting to turn around in a

few years,” Zarate said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |