Regulatory | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Incoming Mexico Hydrocarbons Undersecretary No Fan of 2013 Energy Reform

Mexico has a “historical imperative to reverse” President Enrique Peña Nieto’s landmark 2013 constitutional energy reform, according to the country’s likely next hydrocarbons undersecretary, Alberto Montoya.

Montoya has been tapped for the position by Peña Nieto’s successor, President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the leftist Morena party, who is to take office Dec. 1.

The reform, which allows private sector firms to partner with and compete against national oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) in the formerly state-dominated hydrocarbons sector, amounts to “a betrayal of our country” and the conversion of Mexico into an “economic colony” of the United States, Montoya said in an April presentation at Mexico’s Escuela de Formación PolÃtica Carlos Ometochtzin.

Asked by an audience member whether he thought Mexico could realistically undo the reforms, Montoya replied, “We not only can, but we must,” adding, “this is not an option.”

Now that López Obrador’s coalition has won the presidency and decisive legislative majorities at the national and state levels, reversal of the reform is within the realm of possibility, and efforts to slow down and/or modify its implementation appear imminent.

Following his landslide July 1 victory less than three months after Montoya’s presentation, López Obrador announced his intention to appoint congresswoman and former longtime Pemex engineer RocÃo Nahle as energy secretary and to install Montoya, who holds a doctorate in public policy from Stanford University, as undersecretary.

Nahle and Montoya each have repeatedly expressed the view that Mexico must free itself from dependence on refined products imported from the U.S., and that reversing a rapid decline in Mexican crude output is a job for Pemex, rather than foreign oil companies.

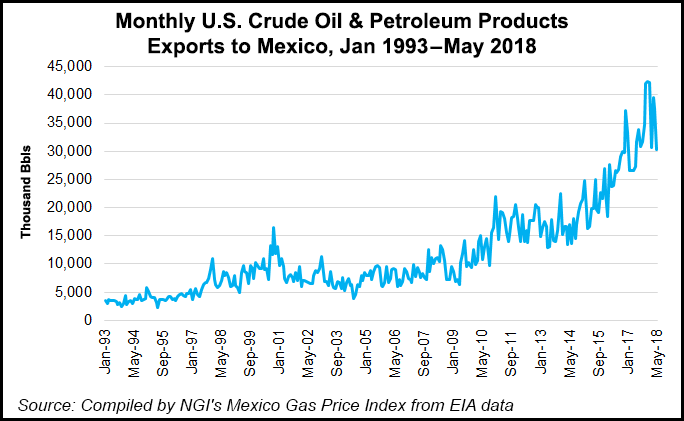

The reform, Montoya told his audience, is designed to stimulate increased flows of crude from Mexico to the United States, and of much more expensive refined products from the United States to Mexico. This dynamic, Montoya said, serves the dual purpose of strengthening U.S. energy security while enriching U.S. refiners and marketers.

“For this reason [the reform] is a betrayal,” Montoya said.

President-Elect’s Platform Reflects Montoya’s View

Although López Obrador has adopted a more conciliatory tone toward the business community since the election, his energy platform nonetheless aligns directly with the views expressed by Nahle and Montoya.

For this reason, “I think that in the end, the more nationalistic side of the team is going to persevere and is going to be the one that dictates energy policy in the country,” Eurasia Group’s Carlos Petersen, Latin America political risk expert, told NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index recently.

Upon announcing his picks for the top energy sector posts, López Obrador, popularly known by his initials AMLO, said his government would earmark 209 billion pesos ($11.1 billion) to rejuvenate the country’s six existing oil refineries and to build one in his home state of Tabasco. He also said he plans to increase Pemex’s annual exploration and production (E&P) budget, with the goal of raising oil output by 600,000 b/d. The latter promise is a departure from the Peña Nieto government, which has sought to increase production by courting private investment in upstream projects.

Montoya has expressed vociferous opposition to the reform’s main privatization tools, which include bid rounds for new acreage, farm-outs of operating stakes in Pemex-controlled E&P licenses, and the migration of pre-reform oilfield services contracts — one of the few ways in which the private sector could participate in Mexico’s upstream segment before the reform — to more lucrative production sharing agreements.

Montoya has said all of these mechanisms offer exceedingly generous fiscal terms to foreign companies while saddling Pemex with a disproportionate tax and investment burden.

In line with this viewpoint, Nahle confirmed recently that López Obrador’s transition team has begun the process of reviewing for “irregularities” all 105 contracts awarded to date through the post-reform bid rounds.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (CNH) recently postponed two onshore bid rounds and a tender for farm-out stakes in Pemex acreage from September to February.

Nahle has said publicly that the continuation of the bid rounds would depend on the findings of the contract review. She also has advocated for increased local content requirements in the bid round contracts, a change that CNH President Juan Carlos Zepeda said may occur in the next tenders.

Analysts Sound the Alarm

Analysts have warned that any delays or business-unfriendly tweaks to the rounds could derail Mexico’s quest to reverse its declining oil output.

Petersen cited that the first post-reform bid round was a flop because the contract terms were not sufficiently attractive for the industry. “And this was a government that really wanted private participation in the country…I cannot imagine a new government that really is not that keen on having private companies operating in the sector [adopting] terms that are going to be that attractive to private companies.”

As evidence that the reform is designed to benefit the United States, Montoya cited a 2012 report prepared by the staff of former U.S. Sen. Richard Lugar (R-IN), who at the time chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The report, titled “Oil, Mexico, and the Transboundary Agreement,” argued that, “Mexico…is important for U.S. energy security, providing a nearby and politically reliable source for oil imports.”

However, the report warned that “falling Mexican oil production and rising demand led to increases in U.S. imports from the Middle East, and maintaining the current levels of Mexican oil production, let alone achieving rapid growth in production, have a dubious future without reforms.”

At the time, Mexico was producing around 2.6 million b/d, a number that has since fallen to below 1.9 million b/d. The report cautioned, “If Mexico does not reform its domestic energy production situation, the U.S. cannot rely on current levels of imports.”

One fact on which Montoya and proponents of the reform agree is that Pemex’s financial and operational performance has been abysmal in recent years. However, Montoya alleges that Peña Nieto’s government deliberately sabotaged Pemex by slashing its budget and diverting crude to the global market instead of to Pemex refineries.

“From day one, Peña took charge of destroying Pemex’s refining capacity,” Montoya said in the presentation.

Through his energy sector “rescue plan,” López Obrador has said he would bring Pemex’s refinery utilization rate to 100%. Pemex’s refineries ran at 37% capacity during the first quarter and produced only 27% of local gasoline and diesel demand, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

Contrary to Montoya’s declarations, major credit rating agencies have warned that delaying bid rounds and diverting resources to the downstream segment could prove calamitous for Pemex, which already is the most indebted oil major in the world.

Montoya did not respond to repeated emails from NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index seeking comment.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |