Markets | Mexico | NGI All News Access | NGI Mexico GPI | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Regulatory

Analysts Fear Lopez Obrador’s Impact on U.S. Refiners, Pemex

The energy platform of Mexico’s next government could negatively impact U.S. refiners and midstream companies, as well as the financial health of Mexico’s national oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), according to analysts.

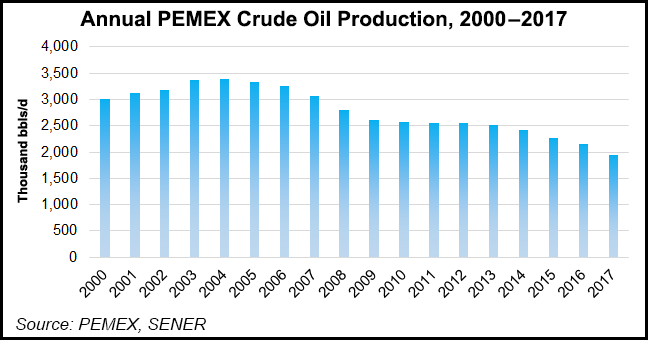

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who is to assume the presidency on Dec. 1, announced at the end of July that his administration would allocate $4 billion to help Pemex boost Mexico’s crude oil output to 2.5 million b/d, up from the current 1.9 million b/d, as well as $2.6 billion over three years to upgrade Pemex’s six existing refineries and $8.6 billion over three years to build a refinery at the Dos Bocas port in Tabasco state.

López Obrador, known by his initials AMLO, also announced his picks for several top energy sector posts, including energy secretary and undersecretary, and the CEO positions at Pemex and state power utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad. All of the proposed appointees have criticized the country’s 2013 constitutional energy reform, which liberalized the formerly state-dominated sector.

The prioritization of the refining segment, and the view that Pemex and CFE should remain the primary actors in the energy industry, amount to a radical departure from the policies of the current government, which has sought to attract private sector investment through auctions and partnerships with the two state-owned behemoths.

“If the new government slams the brakes on outside investment and instead pumps more money into Pemex refineries to boost domestic production, we see two consequences for U.S. refiners and midstream companies,” Morningstar Research’s Sandy Fielden said in a note published Monday. He directs oil and products research.

“The first is a slowdown in U.S. investments in port infrastructure, pipelines, terminals, and storage facilities [in Mexico] associated with opening the distribution system,” said Fielden. “The second is a longer-term slowdown in refined product exports to Mexico as the domestic refineries increase the country’s self-sufficiency.”

Pemex purchased nearly 100% of its diesel imports and 81% of its gasoline imports from the United States in 2017, Fielden said, citing figures from Mexico’s energy ministry. Mexico purchased 54% of total U.S. gasoline exports, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Fielden said that the 2013 reform has unlocked investment opportunities for private sector firms to build fuel storage and distribution infrastructure in Mexico amid steadily growing demand for refined products and declining refinery utilization rates in the country.

He said under the reform, “instead of selling bulk cargoes of transport fuels to Pemex under tender agreements, [marketers of U.S. refined products] can now bypass the state monopoly to deliver product directly into the distribution system, all the way down to retail gas stations.”

However, Fielden said these opportunities could start to dry up if López Obrador follows through on his pledges to boost utilization rates and add new refining capacity.

Policies Could Backfire On Pemex

Although López Obrador’s energy platform aims to restore Pemex to its former glory, his proposals, which also include freezing consumer gasoline prices, could backfire spectacularly on the state energy giant, according to BBVA Research economists Arnulfo Rodriguez and Carlos Serranoh.

Pemex’s refining business lost more than 100 billion pesos ($5.4 billion) annually from 2010 to 2015, Rodriguez and Serrano said in a research note earlier this month, citing figures from Mexico’s Federal Commission on Economic Competition (Cofece), or 0.6% of gross domestic product on average during the period.

“We are convinced that, before investing in the reconfiguration of refineries and, above all, before building a new one, it would be desirable to resolve the company’s efficiency problems,” the economists said. “From an economic standpoint, it does not seem like a good idea to invest 49 billion pesos in an activity that is losing more than 100 billion pesos a year, particularly when we consider that gasoline could be imported at lower prices.”

The comments echo a recent warning from Moody’s Investors Service that López Obrador’s focus on fuel self-sufficiency could threaten Pemex, which posted a net loss of nearly $9 billion in the second quarter, on multiple fronts.

It is also imperative, the BBVA analysts said, for López Obrador to fulfill his pledge to reduce the budgetary allocation for Pemex’s powerful union.

“In our opinion, the burden of Pemex’s union payroll, fuel theft and corruption problems have been the main sources of financial losses in the company during these last few years of higher oil prices,” the analysts said.

The Pemex union has filed, and won, a series of lawsuits preventing the disclosure by Pemex of the salaries it pays to union workers and to union leader Carlos Romero Deschamps, according to Mexican newspaper Excelsior.

Forbes Magazine named Romero Deschamps, who is also a senator and political ally of current President Enrique Peña Nieto, as one of “The 10 Most Corrupt Mexicans of 2013.”

Rodriguez and Serrano added that López Obrador’s promise to increase oil output by 600,000 b/d “does not strike us as realistic, even if it is done by means of public-private partnerships. Boosting oil output in the coming years will also require continuity in the auction rounds of hydrocarbon reservoirs. This factor will be crucial for reversing the decline in oil production and possibly boosting it at a faster rate over the next few years.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |