Marcellus | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Utica Shale

Cabot Working to Resuscitate Old Ohio Oilfields

With one exploratory prospect in West Texas scrapped, Cabot Oil & Gas Corp. continues to work a hunch that the old oilfields of north-central Ohio might hold promise that can be unlocked with unconventional drilling.

The company currently has three permits to drill exploratory wells in three townships in Ashland County, about 50 miles west of Canton, according to Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR) records. A Cabot representative has also told local news media that tests could be done on up to five wells in Ashland and nearby Richland County.

Each of the three sites is permitted for a vertical stratigraphic test targeting the Rome formation, but the real target appears to be formations in the Knox Group, which the company has listed on its horizontal permits. Over the years, the Knox’s three main members — the Beekmantown, Rose Run and Copper Ridge — have been widely developed by legacy oil and gas producers in the state.

The Cambrian-aged dolomite and sandstone rocks, some of the oldest in the Appalachian Basin, all sit below the Knox Unconformity, an erosional surface underneath the Trenton Limestone and the prolific Utica/Point Pleasant formations. The Knox made a name for itself in the 1960s, when more than 30 million bbl of oil and associated natural gas were produced during the Morrow County oil boom, one of the country’s last unregulated gushers that evolved in backyards, cemeteries, parks or anywhere else that leasing rights could be obtained.

In those days, eager operators essentially overproduced the formations, which are also often referred to as the Trempealeau. They moved too quickly on tight spacing and depleted the formation pressures, said Youngstown State University’s Jeffrey Dick, a geology professor who directs the Natural Gas and Water Resources Institute.

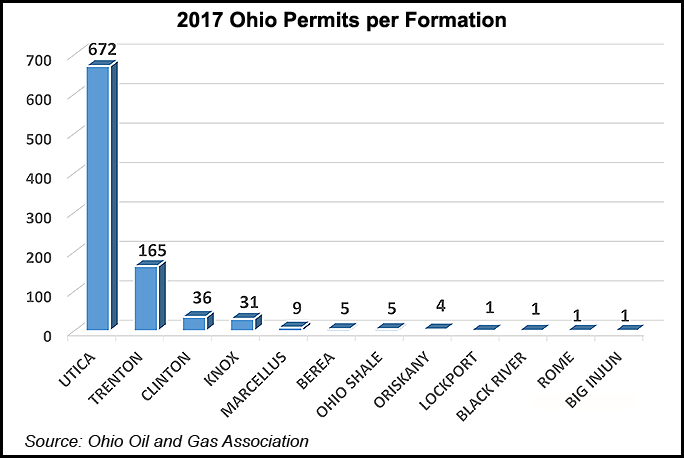

Returning to old areas, though, is nothing new in the unconventional era. In recent years, EnerVest Operating LLC returned to another of the state’s former stalwarts in the Clinton Sandstone to tap oil with horizontal wells and high-volume hydraulic fracturing. Cabot’s new position is west of EnerVest’s current assets in the East Canton oilfield, which was discovered in 1947.

It’s also not the first time an unconventional operator has moved that far west in the state. Devon Energy Corp. was an early entrant into the Utica Shale, securing some of the play’s first horizontal permits in 2011 in Ashland and Medina counties, where it drilled and plugged dry holes. The company continued to permit across a swath of land throughout the next year along the Utica’s western edge, completing unsuccessful wells in Coshocton and Wayne counties in search of black oil. It even drilled as far west as Knox County, which is more than 100 miles west of the play’s core in the southeast, before abandoning the Utica and selling its acreage.

“What Devon ran into was the Point Pleasant contained oil, but it didn’t have the natural gas and formation pressure to drive that oil out, so it’s pretty much dead oil, you can’t move it,” Dick said. “But here, we’re down below the Knox Unconformity, where it can be different. It’s shown in the Morrow County oilfield example that there’s plenty of natural gas formation pressure to drive the oil out. So, it’s significantly different from the shale play in the Point Pleasant.

“Here, you’re dealing with relatively tight formations, but they are not shales. They’re more reservoir rocks, which are openings in the rock that contain the oil. And proven production from the Knox shows that they certainly can produce it.”

In all likelihood, Dick said, the Utica/Point Pleasant is the Knox’s source rock, feeding oil and gas downward through conduits as the clay and shales are compressed.

ODNR spokesman Steve Irwin said Cabot’s early efforts in the Knox are “very, very similar to what you saw in the Utica, where operators would drill a [stratigraphic] well, a vertical well, to see where the formation is and then plug and kick it off from there on a horizontal. It’s the same method, but the permits are just slightly different. It’s a matter of how Cabot has done it.”

Cabot was drilling the vertical leg of the Kamenik well in Green Township in mid-July to the Rome formation in what Dick said is possibly an effort to “know they’ve got through the Knox formations and then they’ll back-up hole and kick out” with a horizontal into the Knox. Cabot has also secured the rights to drill underneath a Columbia Gas Transmission storage field in the area, Irwin noted.

“The operators that are drilling in the Utica have drilled so many wells that they know where the formation is and what they’re doing,” Irwin added. “Cabot’s permits do lend a little bit to the exploratory side of things.”

The Kamenik, Loder Farms and Yeater horizontal permits all list a total depth of between roughly 9,000 and 10,000 feet. Cabot management recently said they would discuss more about exploratory efforts in the region during a third quarter earnings call.

In early 2017, the company said it had identified two new areas where it was wildcatting for oil. After budgeting $75 million for exploration this year, management also said in July that it was ending tests in the Permian Basin, where it had been working in the Alpine High in a wetter area to the west of Apache Corp.’s prolific dry gas position. Management decided to stop allocating capital to the prospect after the company incurred $51.1 million of dry hole costs there during 2Q2018.

While it continues to move ahead in Ohio, challenges remain, said Williams Capital Group LP analyst Gabriele Sorbara. He estimated that Cabot has leased about 75,000 acres in each play.

“They needed a decent amount of scale, both plays have that,” Sorbara said when asked about the estimate. “To be relevant in any play that’s about what you need.” He said the company’s land grab in Ohio is also likely concluding, giving management more room to discuss the play on its next quarterly call.

To be sure, Cabot is a Marcellus juggernaut, producing nearly 2 Bcfe/d from operations in just one northeast Pennsylvania county. While that program was built from grassroots, its other exploration efforts over the years, those in the Tyler formation in Montana, the Chainman Shale in Nevada, the Pearsall Shale in Texas and the Rogersville Shale in West Virginia have generated lackluster results or little excitement.

Sorbara suspected the same might be true of its current efforts in Ohio.

“Even if a new play comes into the picture, I’m not sure how positively that will be viewed if it takes away from a play with a super high water mark,” he said, adding that it’s practically inconceivable to think that oil shows in north-central Ohio would be enough to compete with the company’s prolific Marcellus position.

But Cabot’s management also seems keenly aware of that dynamic and has for now decided to continue testing its luck on the other side of the basin.

“If a new venture did not generate competitive full-cycle rates of return, provide meaningful inventory depth and resource life, and the ability to be self-funding in a low commodity price environment, we would have no problem walking away, and that is where we find ourselves today as it relates to this exploratory area,” CEO Dan Dinges said last week of the company’s decision to pull the plug on Alpine High. He was reminding financial analysts of what management had said last year when it announced the exploratory efforts.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |