Regulatory | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

IEA Hails Mexico Energy Reform as World’s ‘Most Successful’

The International Energy Agency (IEA) praised Mexico’s 2013 energy reform as a model for the world to follow in a new report.

“Mexico is the most successful example of the importance of reform as a catalyst for boosting investment, having embarked [on] a comprehensive shake-up of its oil, gas and power sectors in 2013,” IEA said in its World Energy Investment 2018 report published Tuesday.

“The combination of the opening up of its oil and gas sector to national and foreign companies by eliminating the monopoly of Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), attractive fiscal and regulatory terms and very encouraging hydrocarbons discoveries have stimulated significant enthusiasm with most of the major international operators now present in the country,” researchers said.

The report comes as investors seek to decipher the energy priorities of Mexico’s president-elect, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), who has criticized the reforms in the past as being a giveaway to foreign oil companies.

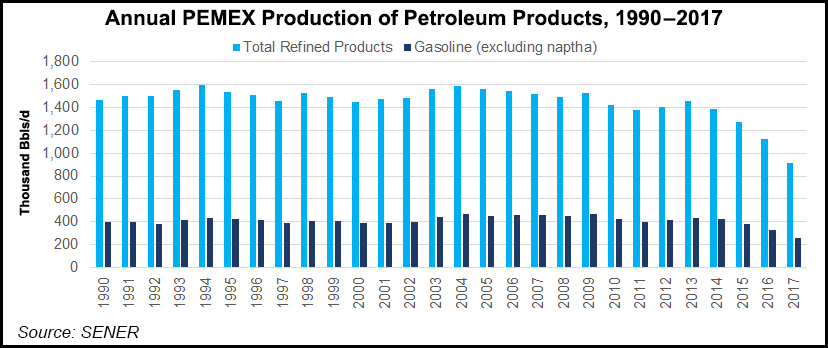

While the outgoing administration of President Enrique Peña Nieto has prioritized upstream bid rounds in order to reverse declining output and replace dwindling reserves, AMLO and his would-be energy minister, RocÃo Nahle, have said they will focus initially on shoring up Mexico’s refining capacity in order to reduce dependence on gasoline imports from the United States.

IEA’s researchers corroborated some of those concerns. “In Mexico and South America, underinvestment in refinery maintenance has forced refiners to cut operating rates and resort to product imports,” they said. “Mexico, Venezuela and Brazil have reduced their refining throughput by a combined 1.6 million b/d since 2015, explaining the 2.3 million b/d increase in U.S. refined products exports into this region.”

AMLO will assume the presidency on Dec. 1, with the national hydrocarbons commission (CNH) scheduled to conduct two previously scheduled upstream bid rounds in the interim. Pemex has also scheduled a farmout tender for operating interests in seven onshore blocks for Oct. 27. AMLO and his team have signaled that bid rounds could be temporarily halted once he takes office.

“When I look at the platform that’s out there, it [appears] very sentiment-driven and not very specifics-driven,” said Sarah Ladislaw of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in an interview with NGI’s Mexico Gas Price Index. “To me, that looks like an opportunity to influence how the [AMLO] administration thinks.”

CNH President Juan Carlos Zepeda, a proponent of the reform who was appointed to a second five-year term in April 2014, has said that Pemex, which posted a $17.8 billion net loss for 2017, should consider an initial public offering (IPO) for a minority stake to improve its performance and transparency.

In a July 9 note published by the Pulso Energético think tank, Zepeda argued that a logical first step would be to create a listed Pemex subsidiary, emulating what China’s 100% state-owned China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC) did when it created subsidiary PetroChina. By following the “Chinese model,” Pemex could conceivably launch an IPO in under two years, Zepeda said.

“Of the 73 [oil and gas] companies that operate today in our country, Pemex is the only one that can’t raise capital on the stock market, in addition to being subject to budgetary control and heavy fiscal terms,” Zepeda said.

Since energy reform was implemented, CNH has carried out 14 bidding processes, resulting in the awarding of 107 contracts to 73 firms, with “very favorable” conditions” for the Mexican government, he said. Zepeda estimated that from 2018-2021, an average of 26 offshore exploration wells a year will be drilled in Mexican waters, more than at any point in the last 30 years.

Although offshore final investment decisions are expected to remain sluggish in 2018, IEA said 2017 “appears to have been a turning point for the offshore sector,” and that deepwater resources sanctioned in 2017 had reached their highest point since 2013.

“The main contributor was Brazil, where the combination of tremendous potential in its pre-salt basins and upstream policy and regulatory reforms, including a new bidding process, eased local content requirements and the abolition of Petrobras’ [Petróleo Brasileiro] exclusive rights to manage the pre-salt area, have created conditions for several international companies to invest in the country.”

Whether Pemex follows the model of national oil companies such as Petrobras, whose shares trade on the New York Stock Exchange, and Saudi Arabia’s Saudi Aramco, which is considering whether to launch what could be the world’s biggest IPO between now and 2019, could play an important role in determining the fate of Mexico’s oil and gas sector, according to Zepeda and other experts.

“I think for most of us in the industry that’s the conventional way from here to there,” said Ladislaw, who cautioned that she is nonetheless skeptical of the prospects for a Pemex IPO under AMLO. “I genuinely don’t know what he’ll ultimately want to do there, but I think that there are a number of voices in the oil and gas sector in Mexico that understand the trajectory that’s necessary.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |