Markets | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

LNG Buyers Not Homogenous, but Shorter, Flexible Contracts a Draw

Liquefied natural gas exporters have a smorgasbord of options to offer buyers as the global market expands, but one thing is clear: it’s no longer only for long-term buyers.

During a lively discussion Thursday at the World Gas Conference (WGC) in Washington, DC, some of the top global gas sellers and buyers shared their wisdom about what’s ahead for the evolving marketplace.

Moderator Susan Sakmar, a visiting assistant professor at the University of Houston Law Center, noted that by the end of this decade, there are expected to be six U.S. export facilities online that could add about 70 million metric tons/year (mmty) of capacity to the market. A dozen or so U.S. projects also are on the drawing board awaiting sanctioning, with another in British Columbia and one expected in Alaska.

She laid out the parameters, then gave way to some industry heavyweights who offered their take on what they think will make or break the projects.

Cheniere Energy Inc. Chief Commercial Officer Anatol Feygin was joined by Pavilion Energy Group CEO Frederic Barnaud, Tellurian Inc. Vice Chairman Martin Houston, Petronet LNG Ltd. CEO Prabhat Singh and Venture Global LNG Co-CEO Michael Sabel.

Cheniere Sets The Table

Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG facility was, until a few months ago, the only Lower 48 project exporting to overseas destinations. Dominion Cove Point in Maryland has since begun commercial operations. But there’s no doubt, and the panel agreed, that Cheniere has set a high bar in how to secure and maintain customers.

Feygin gave credit to former Cheniere chief Charif Souki, who was ousted in 2015 shortly before Sabine Pass began exporting. Souki and Houston, who was a former LNG expert for BG plc, then formed Tellurian Inc.

“Few have had as big an impact on the evolution of the business model and where we are today,” than Souki, Feygin said. In essence, he said the Cheniere model gave the U.S. LNG business legitimacy on the world stage and helped “democratize” the system by offering customers “a variety of models…”

Cheniere has set the pace for U.S. exports, and while many other North American projects remain in pre-sanctioning mode, the company has two more Gulf Coast projects in the queue: Freeport LNG and Corpus Christi LNG, which together would give the Houston-based operator a total of eight LNG trains.

“We continue to move forward with the business model to let the world partake in the bounty that is U.S. natural gas,” Feygin said. “We pass that through to our customers and try to do that as efficiently as possible and as economically as possible. Obviously, it competes effectively globally…”

Cheniere today moves most of its gas volumes into Asia, with contracts underpinning the planned Corpus Christi project through state-owned China National Petroleum Corp.

“We continue to advance those rapidly growing markets that have the appetite for the business model and for the transparency of pricing that it offers,” Feygin said.

Pavilion Believes In Basics

Barnaud said LNG trading “goes back to the basics, you know…to match supply and demand.” Pavilion, a Temasek subsidiary, is a pure-play global gas/LNG integrated player based in Singapore, and it supplies about one-third of all the gas consumed by Singapore industries. Subsidiary Pavilion Gas in April received its first LNG cargo, supplied by Qatargas, under a spot contract for delivery to downstream customers.

“I think the way the energy market has evolved has forced an evolution…a matchmaking process,” about which Barnaud is optimistic. “We are probably much more confident about LNG supply this year; the terms are acceptable, and the prices will bring some visibility for the next decade, or so,” in large part to growth from U.S., Australia and Canada production.

However, Barnaud said the “other side” of the LNG equation, i.e. demand, remains a concern.

“The way this evolution and matchmaking…is going to be reshaped is an interesting concern to us,” He said. “It’s very much about a few buzzwords…One of them is and will remain ’affordability’ so that it remains visible for some time, so that demand effectively can be created.”

For example, stable supply is “very much needed” in India and smaller countries that need the assurance for the citizens that the transition from oil and coal will be seamless.

“It’s important that there is liquidity in the market, that there is liquidity on the physical side, and again, U.S. projects will continue to contribute for a long time,” Barnaud said. Most projects today have flexible destinations and few trade restrictions.

Suppliers also need “price visibility and a market price for LNG,” which is not yet in place.

“How do we achieve a price marker for LNG that will simplify trade and defuse the very high risk?” Barnaud asked. It’s not only balancing the risk and liability, “because contract prices diverge so much from the market price that it creates bias in the relationship…

“So this new fact is something we need to work on.” There is “comfort from the supply side, but the demand side is equally important to ensure it will work.”

Tellurian Turns Tables

Tellurian, whose proposed Driftwood LNG export project would be sited on the Gulf Coast, has a unique model for potential LNG buyers that is unlike anything else working today in North America.

Tellurian today is producing gas from the Haynesville Shale, and wants to build out a three-legged pipeline system to transport gas from the Haynesville and Permian Basin to feed the exports. It’s an expensive proposition, one in which it is attempting to line up investors to underpin the infrastructure build and long-term viability.

French major Total SA has a near quarter stake, and GE Oil & Gas also is a major investor. However, the Driftwood project has yet to be sanctioned as it scour for more partners to underpin its projects. Houston made the case that it is “the moment” for the United States to take advantage of its vast gas stores.

“Infrastructure needs to be get built…but it will get built,” he told the audience. “What matters going forward for me is cost…We talk a lot about it,” but everyone should consider what that actually means. Cost “should be the only thing that matters…New LNG must be low cost at all costs.”

Making a commitment to build also means making a commitment to supply, he said.

Tellurian is “truly a cost-plus producer,” with everything needed basically under one roof. “Now, we’re asking the customer to invest only because we think most of our customers have a lower cost of capital than we do…”

To further compress the costs, Tellurian is integrating the upstream into the business model, giving the proposed Driftwood LNG facility a ready supply of gas.

He admitted that the model may confuse some people because it’s not like other LNG export/import models.

“In very simple terms, what it does is buy the efficiency of buying resources today, which are relatively cheap, and in a number of years they will not be. And by building our pipeline network north, south, west and east, accessing a large number of geographically dispersed basins, we’re able to compress the hub price…”

For example, at a gas price of around $3.00/Mcf, if Tellurian were able to access the hydrocarbons at lower than the Henry Hub price, “once that’s locked in to our infrastructure and to our reservoirs of natural gas, we can maintain that and therefore take another $1.50 outside the traditional chain.”

”Stealth Mode’ at Venture

Meanwhile, Venture Global has been working in “stealth mode” on two Gulf Coast LNG export projects, Calcasieu Pass and Plaquemines LNG. The WGC is “one of the very few public discussions we’ve ever participated in,” Sabel noted.

Initially, Venture pursued an LNG business in Southeast Asia and quickly discovered that the “competitive advantage in most transactions” evolved around cost and flexibility. The company pivoted in 2010, as burgeoning U.S. unconventional gas supplies made it more likely the country would one day export, rather than import, gas.

Venture’s strategy was to take advantage of being “permanently parked” next to U.S. pipeline gas on the Gulf Coast to make its supply attractive to potential customers.

“At the very beginning of this effort, we were certainly building on the foundation of the success of Cheniere,” Sabel said. Venture has modeled flexibility in its contract terms, but it’s not likely to compete against “a Cheniere,” Sabel said. However, “there’s demand for all of the projects in a growing market,” and he expects most projects will succeed in a variety of models.

Sakmar posed the question of whether contracts for 20 years or longer are even needed anymore.

Sometimes a long-term contract is what a customer wants, said panelists. There’s “huge participation” in the LNG marketplace, as it’s part of “one gigantic energy market,” Sabel said. Buyers have different needs and the market is not homogeneous.

“The vast majority of LNG is for electricity production,” he said, and those buyers need to have a “stable supply of fuel at stable price” long term.

The long-term contract option is almost always a part of an LNG supplier’s portfolio, Sabel said. While there has been been a reduction in long-term contracting in the past few years, “it’s still a big portion of the market.”

Suppliers are innovating and creating flexibility for different types of customers.

Industry ”Moving Short’

“This industry is all things to all people,” said Houston. “It’s not homogeneous at all…”

In India, for example, Singh’s goal is to serve local markets with local pricing. But India is “different perhaps than long-term markets…Indexation is valid” versus using a hub index.

Petronet’s Singh said what an LNG buyer wants is affordability and sustainability of supply. Supply doesn’t have to be the cheapest, but it has to have an affordable price.

The Indian-based LNG operator has two LNG receiving and regasification terminals, and is in the process of building a third. Gaz de France is a strategic partner, and it has sales and purchase agreements with Ras Laffan LNG Co. Ltd. and Qatar.

“The industry is moving short,” Houston said. “There is no need for long-term contracting anymore. Now I don’t mean to say that it’s going to be easily financible…We need a new business model in this industry and through slow evolution, we’re getting there…”

The emerging models for contracting or selling spot LNG “creates tremendous opportunities for buyers and bespoke solutions,” Feygin said. Cheniere plans to continue to evolve and “push as much as we can…

“What got us here…were 20-year contracts,” he said. “Now some are flexible,” but Cheniere still pursues 20- and 25-year contracts. “But we can tailor solutions and commercial offerings…”

There also is “burgeoning liquidity in global LNG but nothing compares to Henry Hub,” Feygin said. He noted that last year Henry Hub volumes were 50 times larger than the Japan Korean Marker, or JKM.

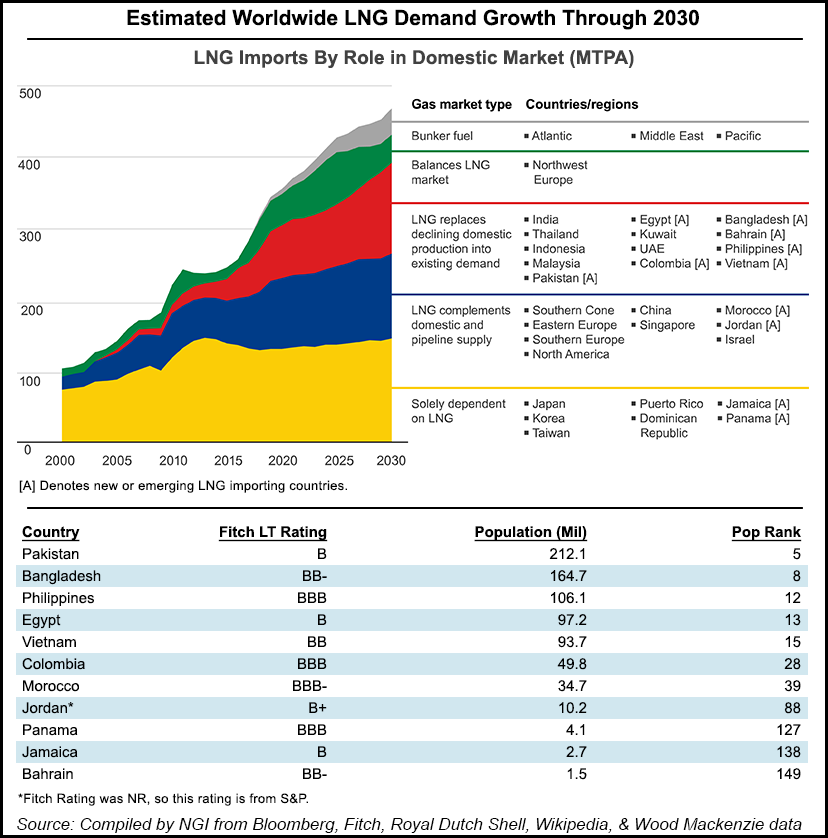

“We’re going to continue to evolve and find different business models, as this industry grows from 300 mmty to 500 mmty in the next 10 years,” Feygin said.

Contrarian View

Barnaud is unsure the Tellurian model to have buyers underpin supply is a good one. He agreed to disagree that buyers would want to buy reserves and pay for an export project.

“U.S. projects, I love them, but if you expect buyers to underwrite them, essentially with $1, $2, $3 billion…investments, it’s not going to happen,” Barnaud said. “Let’s get real…The contracts are mostly free destination…free to trade, but the contracts are not that good. They are very complex to the operator…so this is not an improvement on trade…

“I think we also need in the U.S. to step back and improve the way the next LNG is going to be traded. The first few contracts there was a diversification strategy…Now we need more flexibility, but LNG is too complex to trade. It’s easy to buy coal. It’s easy to buy oil…

“It’s not that easy to trade LNG because the contracts are outdated, whether they are long-term or short-term, master agreement, it’s outdated.”

The beauty of LNG, Barnaud said, is that it doesn’t have quality issues and cargoes can go nearly everywhere.

Promoting more flexibility and more market pricing, whether it’s through some trading platform, whether it’s indexation “is absolutely critical,” he said. There may be one-year take-or-pay contracts, but but not 20-year take-or-pay. “This is absolutely ridiculous…” The project has to be affordable for buyers in the long run.

Tellurian’s Houston said “a lot has changed in the fabric” of the LNG business even in three year’s time when the last WGC was convened. Today, “the barriers to entry are almost nonexistent. The development of markets has been almost unprecedented.”

Not too long ago, “there were so few players…and now there so many new buyers and all the activity and fragmentation of the industry is huge,” he said. “That’s the great opportunity…and there are open price signals to make this a truly commoditized market.”

There have been “enormous” developments on the supply side, Houston noted. “We’ve seen the troika of Qatar, Australia and now the United States, really they’ve put themselves firmly on the map as a three-legged stool…But on the horizon, keep your eye on Russia. It won’t be long before Russia is the fourth leg of the stool…It won’t be long before the three-legged stool is a four-legged table.”

Big technological strides have been made in the LNG industry, Houston said. “But the thermodynamic principles of LNG, compression, steel to make stuff, wherever it comes from…it’s a true commodity. Its principles have not changed…The mechanics are still the same as they were in 1969…”

The political landscape has changed and dramatically in some ways, but “at the end of the day, even in ”tweetspeak,’ it hasn’t changed that much…Tariffs come and go, spats come and go, sanctions come and go…

“I’m prepared to say the path is clear for future developments,” said Houston. What’s not changed is that the United States has become “the supplier of choice. This is the place to be. This is where future development should be.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |