E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Replication of U.S. Shale Revolution in Other Countries No Easy Feat

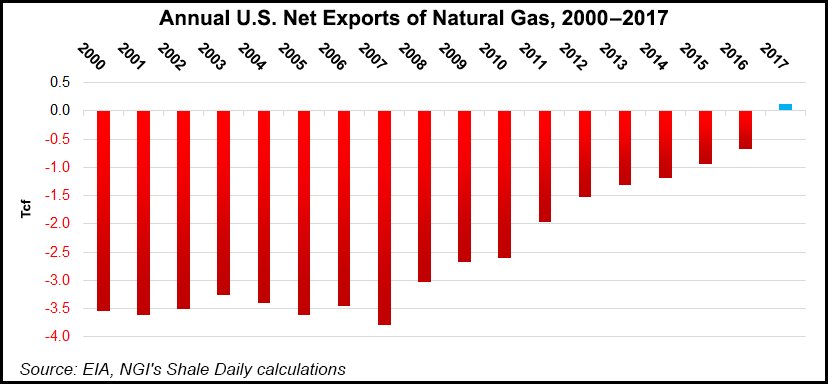

The shale gale has been the driving force enabling the United States to shift from being dependent on foreign energy to becoming a net natural gas exporter, but don’t expect similar transformations in most other shale-rich countries any time soon, a group of officials from international companies said Wednesday.

In 2005, domestic natural gas production was 47 Bcf/d; this year it will be an estimated 81.2 Bcf/d, and the United States is a net exporter of natural gas. Shale gas makes up 60% of current U.S. production, said Philippe Chariez, senior technical advisor for Total SA, during a panel discussion at the World Gas Conference (WGC) in Washington, DC.

“So the U.S. is today fully gas independent, and that should mean that it should soon be a major LNG [liquefied natural gas] supplier,” Chariez said.

The U.S. shale revolution was built on four pillars, Chariez said, including extensive knowledge of the nation’s subsurfaces, fluid and competitive markets and full political support from three successive presidential administrations. The fourth and most important pillar, he said, is the U.S. practice of subsurface ownership going to landowners, rather than to the government.

“That means that the market and the gas production is extremely flexible and reactive, compared to other countries.”

Replicating shale’s U.S. success in other countries won’t be easy, even though shale gas formations exist in nearly every region of the world, Chariez said, because those four pillars aren’t replicated elsewhere.

“This fantastic U.S. revolution cannot be necessarily replicated everywhere in the world,” he said.

A combination of factors, including large resources, favorable geology, steady advancements in technology, and existing infrastructure enable unconventional gas to become a rapidly growing, low cost source of supply in North America, according to Vello Kuuskraa, president of Advanced Resources International. But while the United States has the largest global shale gas resource at an estimated 32.9 Tcm, there are other countries also boasting large resources, including China at 31.6 Tcm. Seven countries account for 70% of the 222 Tcm (nearly 8,000 Tcf) of global shale gas, Kuuskraa said — the United States, Canada, Argentina, Algeria, Canada, Mexico and Australia.

In addition to its massive conventional resources, Russia sits on some of the world’s largest unconventional gas deposits, estimated at 48 Tcm, most in western Siberia, but has yet to fully develop them, said Tatiana Mitrova, director of the energy center at the Moscow School of Management.

“Underneath all of these enormous conventional gas reserves, there is a lot of unconventional gas, tight gas, shale gas. Why isn’t it developed? Well, the answer is quite simple: when you have such an enormous amount of conventional, cheap gas…why the hell would you go through drilling and producing shale gas,” which would cost much more. “It doesn’t make any economic sense, and therefore there is no exploration and there is no real assessment of the reserves.”

Despite having some of the world’s richest shale gas resources, Argentina is not energy self sufficient, said Philippe Dupuis, director general of Total Austral. A decade ago the country was a net exporter of natural gas, but today it imports 25% of the gas it needs, and as much as 40% in winter. The country’s previous leaders’ energy policies, which included central government control of production and prices, handicapped Argentina’s energy industry. But a new incentive package adopted by Argentina’s current administration could change that trend, Dupuis said.

“Argentina has clearly the potential to fulfill its gas demand…Argentina can start to become once again, probably not within the next few months, but the next few years, a gas exporter. Not very quickly a natgas exporter, but within a couple of years? Yes, probably.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |