Infrastructure | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexican Natural Gas Marketers See Emerging Need for Commercial Storage

Participants in the Mexican natural gas sector see a budding need for commercial storage capacity, but they also say the market and its infrastructure still have some ways to go before demand materializes.

“I think the question we are all asking is: Can commercial storage pay for itself in Mexico?” Tenaska Marketing Ventures Inc.’s Geoff Street, director of marketing, told NGI’s Mexico GPI.

“Without significant seasonal demand volatility and with power and gas markets that are still developing, this is a very difficult question to answer. We would like to see less state participation in the price formations for these commodities, which might give the market a clearer signal if and how much storage is necessary.”

The Energy Ministry (Sener) published earlier this year a public policy that calls for constructing 45 Bcf in strategic natural gas inventories by 2026. The government expects these inventories, which would be reserved for supply emergencies, to pave the way for a commercial storage market.

Developing the inventories falls to the Centro Nacional de Control del Gas Natural (Cenagas), the state-owned operator of Sistrangas, Mexico’s main gas transmission network.

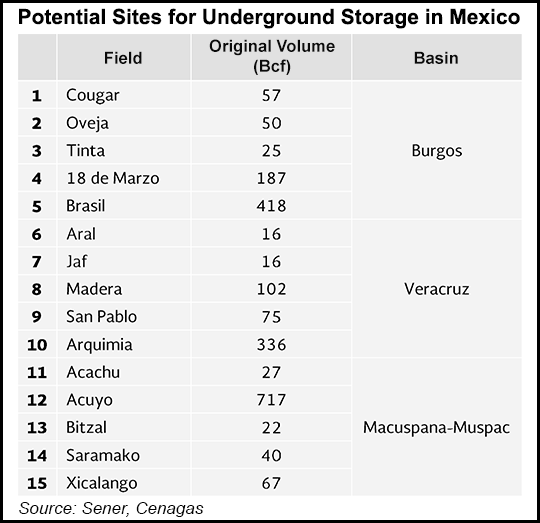

For its first storage tender, expected to launch later this year, Cenagas is currently soliciting industry feedback on four candidate sites — all of them depleted oil and gas reservoirs. The tender is expected to contract at least 10 Bcf of the 45 Bcf target.

As part of the tender, Cenagas is required to organize an open season to identify demand for commercial storage capacity, which could then be incorporated into the bidding process. The eventual winner may also hold an open season for additional commercial demand.

A survey of Mexican shippers taken last September to October determined there was commercial demand for storage capacity of 3.68 Bcf, just under half of daily national gas consumption and less than one day of pipeline imports from the United States.

“Is there is a commercial need for natural gas storage? I think the answer is yes, although location is critical,” CEO Santiago Garcia of Santa Fe Gas LLC told NGI’s Mexico GPI. Santa Fe is the marketing affiliate of Mexican pipeline company Fermaca.

For example, northern Mexico, which includes the industrialized northeast region, has a greater need for commercial storage, he noted. However, Mexican facilities in that area would also have to compete with storage providers in the United States. The U.S. South-Central storage region, which includes Texas, has a combined design capacity of 1,558 Bcf working gas.

The four candidate sites proposed by Cenagas run north to south, along the eastern side of Mexico. Only one would be selected for the the first tender.

The south part of Mexico has less gas demand than the central and northern regions, although the Yucatan Peninsula on the southeastern tip of Mexico suffers from persistent supply shortages and may benefit from access to the strategic gas inventories.

Garcia also noted a potential need for commercial storage services among oil and gas operators in the south, where some of Mexico’s most active exploration and production basins are located.

“In Mexico, we tend to see everything from the demand side,” Garcia said. “But keep in mind that in the Gulf of Mexico area, with all these new developments both onshore and offshore, it’s not out of the question that we might need some storage capacity for those producers.”

Energy Security

Sener’s target of 45 Bcf working gas, equivalent to an expected five days of demand in 2029, is intended to shore up Mexico’s energy security and would only be withdrawn during shortfalls in the gas supply, which is increasingly dependent on “continental” imports from pipelines on the U.S. border.

Mexico lacks underground gas storage facilities, relying instead on liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals for short-term system balancing. Until the strategic reserves are in place, Cenagas plans to hold operational inventories at the two active LNG import terminals — Manzanillo on the Pacific Coast and Altamira on the Gulf Coast.

The Energy Ministry expects to publish later this year a natural gas emergency plan that would regulate the specific uses of the 45 Bcf. The strategic inventories are to provide system-wide coverage on both the Sistrangas and the major private pipeline systems being developed outside of the main transmission network.

However, an industry source critical of the Sener policy noted that it does not include regional storage targets that account for transport restrictions on the various pipeline networks within Mexico.

“One can get storage in a certain location, but it will fail to really reach its objective on a regional basis, due to the fact that some regions of the country are not interconnected to the main gas pipeline system (Baja, for example), or that there are transport bottlenecks between regions,” the source told NGI’s Mexico GPI. “Therefore its impact on a potential shortfall will be limited at best.

“It’s much more desirable to resolve the operational storage first since there is infrastructure already available, such as underutilized gas pipelines (when all remaining pipes come online) and LNG tanks, which will be of no use anymore when continental gas reaches its maximum.”

The policy states that Cenagas must promote the development of pipeline and interconnection infrastructure necessary to ensure that the strategic inventories can provide national coverage.

The industry source was also critical of the policy’s rationale for determining that Mexico needs strategic storage. The source argued that the conclusions did not fully consider gas from the Permian Basin, namely, the Comanche Trail and Trans-Pecos pipelines in West Texas, which both ramped up last year. On the Mexico side of the border, Comanche Trail injects gas at San Isidro and Trans-Pecos at Ojinaga, both in the northwest state of Chihuahua.

Delays to downstream pipelines have constrained flows at both Comanche and Trans-Pecos, although most of the outstanding projects are expected to start up by the end of this year.

“Each one of these pipelines will be able to move 1.25 Bcf/d into Mexico,” the source said. “Roughly 1.1 Bcf/d of this gas will flow to the Pacific Northwest of Mexico and over 1 Bcf/d to the states of Durango, Aguascalientes and Jalisco, and even be able to move east perhaps to the Gulf of Mexico. This source of gas should definitely be taken into account for analysis of the rationale behind the document.”

However, a Sener official said the policy document centered on demand areas, rather than supply. David Rosales, director general of natural gas and petrochemicals, explained to NGI’s Mexico GPI that this focus was due to the ministry’s guiding concerns of energy security and emergency planning.

The model used in the document, he added, did consider supply sources from current and expected pipeline systems, including future imports from the Waha Hub in the Permian Basin, as well as from Agua Dulce in South Texas and from Tucson, AZ.

“It’s true that flows from Waha are the least clear, but this is because most of the volumes on the system that receives gas at Ojinaga and San Isidro won’t reach Sistrangas,” Rosales said. “There is demand expected on the system from Waha up to Guadalajara, where it will connect with Sistrangas.

“The volumes that will flow on that route to Guadalajara aren’t completely defined because the power plants that will operate along it have yet to be defined” per the rules of the wholesale electricity market. “Therefore, there is some uncertainty on that specific route preventing the model from determining exactly how much of that volume will reach the Bajio region,” past Guadalajara.

Socialized Costs

The cost of building and operating the strategic storage projects and associated infrastructure is to be “socialized” through a tariff mechanism applied to all shippers on Sistrangas and the private systems. Mexican authorities have yet to release any details on how that mechanism would work, but they have indicated the tariffs would be proportional to the volumes transported on each system.

“Considering that the strategic storage project is meant to provide natural gas security for all users and that the government will control how and when the gas is used, I don’t see any alternative to socializing the costs across all users,” Street said.

“Sharing the costs for the strategic project shouldn’t necessarily affect the natural gas market, or even the power market,” he added. “However, if the government chooses to use the gas in the strategic inventories as a pricing tool, then that could have an impact on market development.”

The tariff mechanism could require some changes to regulations for the electricity sector. Current rules do not permit generators to include storage costs in their bids into the wholesale power market.

The government’s market monitor for generators “has a manual, which basically states price caps per generator depending on the region,” the industry source said. “The manual does not recognize storage as an authorized pass-through cost. This is an absolute must if all marketers and users of gas transport capacity will incur in strategic storage costs.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |