E&P | NGI All News Access | Regulatory

‘Much Uncertainty’ About Limits of Alaska’s ANWR Production, Says EIA

Market dynamics, coupled with an uncertainty over how much oil and natural gas is under the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), could limit the amount of increased Alaskan production that is processed domestically, according to a study released Wednesday by the Energy Information Administration (EIA).

EIA’s Dana Van Wagener, senior operations research analyst and the study’s author, said there was “much uncertainty” surrounding the ANWR projections because oil and gas production hasn’t started yet and the only well drilled in the coastal plain, aka the 1002 Area, was completed in 1986. According to Van Wagener, the results from that test well remain confidential.

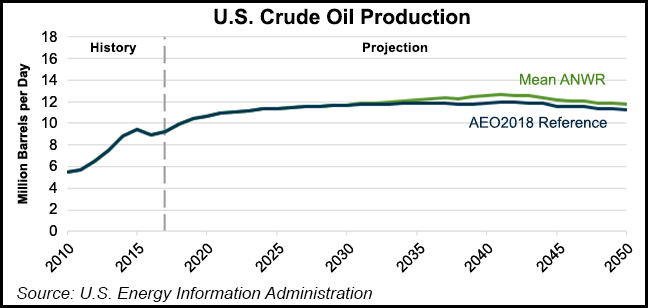

Under a middle resource, or statistical mean, scenario, cumulative U.S. crude oil production from 2031 to 2050 would increase by 3.4 billion bbl compared to the reference case contained in the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2018 (AEO2018). Production in ANWR would not start until 2031 because of the time needed to acquire leases, conduct exploration activities and develop any necessary infrastructure.

The mean ANWR scenario also projects that for every additional bbl of crude oil produced from ANWR, U.S. net imports of liquid fuels would be reduced by about one bbl.

Similarities abound between the AEO2018 reference case and the mean ANWR scenario. Under the AEO2018 case, U.S. net imports of crude oil, petroleum products and natural gas liquids (NGL) are projected to decrease between 2017 and 2035.

“The United States is projected to be a net exporter of liquid fuels on a volume basis from 2029 to 2045, with net exports peaking near 650,000 b/d in 2037,” Van Wagener said of the AEO2018 reference case. “After 2045, U.S. net imports increase, reaching almost 750,000 b/d in 2050.”

Meanwhile, under the mean ANWR scenario, a similar pattern is projected for net liquids fuels imports. According to Van Wagener, net exports of crude oil and liquid fuels would exceed 1.2 million b/d by 2040. U.S. net imports are projected to increase to about 300,000 b/d in 2050.

Van Wagener added that the reduction in U.S. imports of crude oil and petroleum products would improve the domestic balance of trade,

“In the AEO2018 reference case, cumulative U.S. expenditures on imported crude oil and petroleum products are about $4.9 trillion — in 2017 dollars — between 2031 and 2050,” Van Wagener said. “In the mean ANWR case, comparatively higher domestic crude oil production from 2031 through 2050 reduces cumulative expenditures on imported crude oil and liquid fuels by about $409 billion.”

However, she cautioned that market dynamics could throw a wrench in the projections.

“Demand for gasoline declines on the West Coast through most of the projection period, which could mean tepid demand for additional crude oil to be processed to meet end-use consumption in the traditional market for Alaskan crude oil production,” Van Wagener said. “The availability of Jones Act-compliant vessels and constraints through high-traffic waterways on the West Coast could also limit the amount Alaskan crude oil that gets processed in domestic refineries.

“Given these factors, some additional volumes of Alaskan oil production would likely be exported to Asia.”

‘Considerable Uncertainty Remains’

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the portions of the 1002 Area controlled by the federal government hold an estimated 7.7 billion bbl of technically recoverable oil. The USGS estimate climbs to 10.4 billion bbl with the inclusion of Native lands and adjacent state-controlled water areas within a three-mile offshore boundary.

Van Wagener characterized the effect of opening the 1002 Area to development as “highly uncertain” because of several factors, beginning with the fact that little is known about the underlying geology of the entire ANWR region.

“The USGS oil resource estimates are based largely on the oil productivity of geologic formations that existed in the neighboring state lands in Alaska as of 1998 and two-dimensional seismic data that had been collected by a petroleum industry consortium in 1984 and 1985,” Van Wagener said. “Consequently, considerable uncertainty remains regarding the size and quality of the oil resources that exist in ANWR.”

There are also questions about the size and quality of any underlying oilfields, as well as uncertainty over the legislative environment. Development of the 1002 Area, considered unlikely for decades, only became a serious concept after Republicans in Congress attached a controversial policy rider to a comprehensive tax reform bill signed into law last December. Nevertheless, such development is still considered to be years away.

However, ANWR production could help alleviate problems along the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), according to Van Wagener. TAPS currently carries about 500,000 b/d, down from a peak of 2 million b/d in the late 1980s. Lower flows can lead to problems with wax and/or ice accumulation, so any additional crude oil from ANWR could be instrumental.

“The exploration, discovery, and development of new oilfields in ANWR ultimately will depend on the assumed timing of development, the assumed field size distribution and production profile for each field size, and the expected profitability of development of each field size,” Van Wagener said.

The study’s methodology assumes the first lease sale would be conducted in 2021, with first production from ANWR within 10 years of the initial lease sale. It also assumes that larger oil and gas fields would be brought online first; new fields would be sequentially developed every two years after a prior field begins production; and fields would take three to four years to reach peak production.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |