E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexican Energy Secretary Cautions Oil, Natural Gas Industry Success to Take Time

Halting the decline of Mexican oil production won’t produce instant success, said Energy Secretary Pedro Joaquin Coldwell on Tuesday.

“Oil is a long-term business,” he said at a convention in Mexico City. “Exploration takes time. For example, returns are not expected in deep waters within at least seven or eight years.”

Joaquin Coldwell was speaking at the convention of Amexhi, which is the Mexican association of oil and natural gas companies, except for the country’s largest, state-owned Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

The secretary was addressing a wider audience than the select industry forum. His remarks were presumably meant to generate enthusiasm for President Enrique Pena Nieto’s energy reform during the current campaign for the election of his successor.

Pablo Medina, of the Welligence consultancy, said he was dismayed by the lack of debate on energy issues among the three leading candidates and two independents for the July 1 election. Others who attended the event were of the same opinion.

One of the reasons is undoubtedly that Pena Nieto’s rating in opinion polls is the lowest ever recorded in Mexico since the first light of a democratic era began to dawn in the final years of last century. And energy reform has been the standard-bearer of Pena Nieto’s presidency.

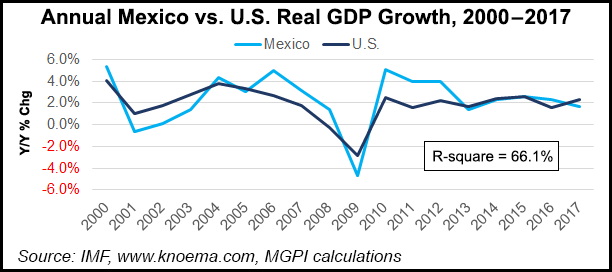

In addition, the Mexican economy, though stable, is undoubtedly stuck. Except for Cuba and Venezuela, Mexico’s growth in per capita income is the lowest of any Latin American country over the last 25 years. So too — stable but stuck, at least for the moment — is the nation’s oil and gas industry.

This year, Pemex is expected to produce a shade more than the 1.948 million b/d of crude it turned out in 2017, Joaquin Coldwell said. This year’s first quarter results point to a further decline. Crude oil production fell to 1.837 million b/d in March, a 9 % decline compared with 2.018 million b/d a year earlier. Natural gas output fell by 14.7%.

By the end of next year, Joaquin Coldwell said the first fruits of the reform are likely to emerge in the first production of crude from the first two auctions in shallow waters in Round One of the reform.

With an eye on the audience beyond the confines of the convention, Joaquin Coldwell warned that any attempt to cancel the existing contracts “would be a threat to the rule of law and the interests of the nation.”

He did not mention the name of any candidate in the current election who might present such a threat, but Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador has aroused suspicions by saying that he aims, if he becomes president, to review all the contracts in order to check for any possible inconsistencies or impropriety.

Not one suspicion, however, has been voiced by any of those concerned in what has universally been rated as a process of immaculate transparency.

The Amexhi convention was the formal presentation in book form of the association’s “Agenda 2040,” which proposes $1 trillion of investments in the Mexican energy industry, including $640 billion in oil and gas, as a product of about 15 more rounds of upstream auctions through 2040.

Amexhi President Alberto de la Fuente, who heads Royal Dutch Shell plc’s Mexico unit, pointed out that association members have already invested about $161 billion in upstream auctions and Pemex farm-outs.

Senior Amexhi official Enrique Hidalgo, who is CEO of ExxonMobil Corp.’s Mexico upstream unit, said it was vital for the energy sector to keep in step with the open economy. A return to the past, he said, in what appeared to be a pointed reference to some of Lopez Obrador’s proposals, “would mean two very different scenarios for Mexico in 2040.”

Nor is the issue one of ideology, said De la Fuente, who added that “by 2040 the production of the fields currently in production will have dropped by 85%.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |