Former Pemex Chief Boldly Claims ‘Corruption is Everywhere’ Within Company

Once a pillar of Mexico’s state-run energy sector, Adrian Lajous Vargas has turned a revealing “kiss and tell” spotlight on an insider’s view of what he said is the inefficiency and corruption of Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

Pemex was a state monopoly when Lajous became its director general for most of the 1994-2000 administration of Mexico President Ernesto Zedillo. Even though Lajous was a controversial figure, he later carved out a prominent career in the international energy industry. He held positions with the consultancy McKinsey & Co., the multinational oilfield services firm Schlumberger Ltd. and as a Morgan Stanley adviser, along with academic posts such as the head of the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies.

No other former Pemex chief has had such a glittering career outside of Mexico. Lajous most recently published a three-part series of articles in the Mexican daily La Jornada on the problems faced by the upstream division of Pemex, now known as Pemex Transformacion Industrial (PTI).

PTI is the most politically sensitive area of Pemex. The tentative measures to install a market in gasoline caused mayhem and pillaging amid protests against price increases early last year in what was the only physical outburst of popular discontent over the 2013-2014 energy reform.

PTI plans to update the Pemex refineries. That, said Lajous, is necessary. But it would require $25 billion and, at the very least, six years to put into practice — not to mention many more billions of dollars that would be required in areas such as transportation and storage infrastructure.

Six years is the length of a complete Mexican political administration, and there is no reelection of presidents. In other words, the next Mexican president, who is due to take office Dec. 1, would have to leave a $25 billion blank check to pass on to his successor.

Lajous, who comes from a family of Mexico’s state technocracy elite, shrinks from stating the obvious. But other prominent members of the elite, such as Jesus Reyes Heroles, who served as Pemex director-general, Energy secretary and Mexico’s U.S. ambassador, have called for an initial public offering, similar to that of Brazil’s state-owned oil company, Petroleo Brasileiro (Petrobras) that raised $70 billion in 2010.

Even a windfall of such proportions, however, would probably provide much more than a respite of the challenges that face Pemex, including the crisis in refining but also in production of both crude and natural gas as the once prolific Mexican fields decline.

Financial results have been of an order in recent years that would have persuaded the shareholders of a private-sector company to seek protection from bankruptcy legislation. Early last year, then-CFO Juan Pablo Newman hailed a 2016 net loss of $14 billion as slashing 60% from the 2015 result. “Finances are stable but can certainly be improved,” Newman said in a conference call at the time.

But the losses have continued, with Pemex racking up a $19 billion net loss in 4Q2017. Lajous said without massive investment and cutting the workforce — neither of which is feasible, at least in the short term — that the refineries will be “trapped by a perverse mechanism. The less crude they process, the less money they lose.”

By contrast, he said the more gasoline and other fuel products the country imports, “the more their losses are reduced.”

In addition, the corporate reorganization that led to the foundation of PTI has obscured transparency by lumping together the figures for natural gas and petrochemicals, then subtracted them from logistics and commercial activities.

The outcome has made it impossible to make comparisons with past years in refining, contributing to the loss of management discipline in one of the company’s principal lines of business, Lajous said. “Greater transparency is essential for the construction of competitive markets,” he added.

“The problems are many, including the way that Pemex and its subsidiaries in general are managed; huge slices of income are transferred to the government and consumers; operations are suddenly slashed by surprise — and often very severe — budget cuts…Pemex managers do not trust companies that are their contractors and vice-versa.”

Lajous gets to the nitty gritty by saying in the La Jornada articles that “corruption is everywhere in all areas and at all levels of the hierarchy…organized crime has moved into the logistical activities of Pemex.”

The organized crime accusation is particularly serious. No senior Pemex executive has ever said corruption is generalized or that organized crime is in some form of partnership within parts of the company.

Despite the controversy that surrounded Lajous, Houston-based George Baker, president of Mexican Energy Intelligence, described him as being “the most prominent intellectual figure in Mexico’s energy sector of his time.” Although he could now be considered a figure whose time has passed, given energy reform.

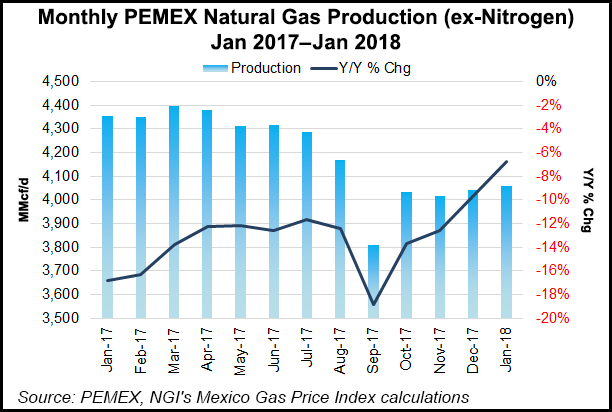

Despite predictions to the contrary made by its executives, Pemex production has been falling sharply year to date.

On Wednesday, the state company reported natural gas production (not including nitrogen) was 3.749 Bcf/d in March, a drop of 14.7 % compared with 4.397 Bcf/d in March 2017.

Crude oil production fell to 1.837 million b/d in March, a 9 % decline compared with 2.018 million b/d a year earlier. Pemex upstream director Juan Javier Hinojosa has forecast that 2018 crude production would average 1.951 million b/d.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 |