Markets | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Waha, Other Points Weak Through 2019, But Henry Hub Gains on Exports, Power Demand, BTU Says

Insufficient infrastructure will continue to limit access for growing natural gas supply to connect with new demand outlets along the Gulf Coast, leading to ongoing and sometimes exacerbated price weakness in those supply basins for at least the next couple of years, according to BTU Analytics (BTU).

Dubbed by BTU as the “arc of pain,” the theoretical, fluid boundary line encompasses all the pipeline constraints out of the various domestic supply basins, including Appalachia, the Permian and Oklahoma’s myriad reservoirs that in general are the South Central Oklahoma Oil Province (SCOOP) and the Sooner Trend of the Anadarko Basin in Canadian and Kingfisher Counties (STACK). All of them are areas that don’t see a lot of demand. Below that arc is where demand is growing, largely along the Gulf Coast.

Already, BTU analysts are starting to see some pipeline constraints from the Permian, and physical pipeline capacity could be exhausted later this year, with shut-ins becoming a risk in the early 2019 timeframe.

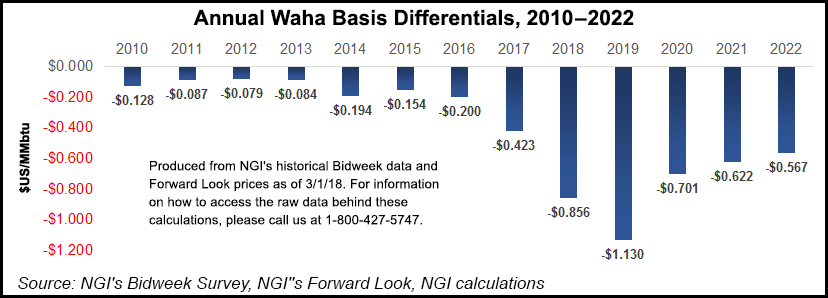

“We’ve started to test these boundaries, and that has translated to a weakening Waha basis,” BTU senior energy analyst Jason Slingsby said at a recent conference in Houston.

Waha gas averaged 10-15 cents below the benchmark Henry Hub in 2016; that discount blew out to around 25 cents in 2017. In fact, Waha fell nearly 50 cents below Henry on a handful of occasions during the year and only on the last two trading days of 2017 did Waha trade at a premium to the Henry as a winter blast, strong demand and freeze-offs hit the region, according to NGI historical data.

“That’s important as we think about moving forward, as we have more production coming online, and those problems are really only expected to get worse,” Slingsby said.

The lion’s share of new dry gas production above that arc of pain line is coming from the Permian and Appalachia, with 6.2 Bcf/d of incremental production coming online in 2018. Production is forecast to reach 12.4 Bcf/d above 2017 levels by 2021 and 14.3 Bcf/d above 2017 levels by 2023, according to BTU.

“So where we’ve already started to test some of these constraints, we expect them to get even worse going forward,” Slingsby said. In fact, BTU expects Waha to trade as much as $2 below Henry Hub on occasion going forward. “It won’t be sustained, but it may be enough to incentivize some shut-ins.”

But the price pain isn’t limited to the Permian and Appalachia. Rockies and Midcontinent prices have also suffered amid increased pipeline flows out of the Permian, which runs through West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. Permian flows on the Transwestern and El Paso Natural Gas systems have resulted in Rockies gas being displaced. And a growth in northbound flows out of the Permian has filled up capacity on Northern Natural Gas.

A look at historical data shows that Northern Natural Gas-Ventura (NNG-Ventura) averaged about 7 cents below Henry Hub in 2016. In 2017, NNG-Ventura averaged at an 11-cent premium, but that’s only because of a one-day spike in prices in the mid-$60 range that skewed the yearly average to the upside. Take away the one-day blip, and NNG-Ventura averaged nearly 15 cents below Henry Hub for 2017, NGI data show.

“All this competition is centering around the middle of the country where we don’t have a lot of demand. You have a lot of cheap gas fighting for this market,” Slingsby said.

Meanwhile, the bulk of demand that is on the horizon is coming from the Gulf of Mexico, where about nearly 4.5 Bcf/d of incremental growth is expected between 2018 and 2021, according to BTU. Exports to Mexico and liquefied natural gas exports are expected to account for more than 70% of that demand growth through 2022.

Infrastructure relief is on its way beginning this year, but it won’t solve everything. In the Northeast, the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline project, an expansion of the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line (Transco) system, is expected to come online in mid-2018, according to project developer Williams. The $3 billion expansion includes 197.7 miles of pipeline and associated compressor stations, equipment and facilities.

Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) and Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) are scheduled to come online by the end of 2019. Each are designed to deliver Marcellus and Utica shale gas into Southeast markets. Each greenfield pipeline is to start in West Virginia before crossing into Virginia to interconnect with Transco. ACP would also extend south into North Carolina.

“If Atlantic Sunrise comes online as expected, this would be a huge relief valve. But it’s not enough to relieve the problem long term. We still need Atlantic Coast and Mountain Valley,” Slingby said.

Out of Oklahoma, Cheniere Energy Inc.’s 1.4 Bcf/d Midcontinent Supply Header Interstate Pipeline (MIDSHIP) is scheduled to enter service in April 2019. MIDSHIP would carry 1.4 Bcf/d of natural gas to connect production out of the SCOOP/STACK to markets in the Gulf Coast.

“In the outyears, as we think about supply continuing to grow, we might see relief in the Northeast, in Appalachia, but we still have a problem that might persist in the Permian because we’re still growing there,” Slingsby said.

Export growth out of Waha isn’t likely until projects just south of the border come to fruition. BTU expects Waha to serve about 25% of the 7.5 Bcf/d in power plant demand coming from Mexico in the next five years.

The most notable among those is the Aguascalientes-Villa de Reyes-Guadalajara pipeline, which is expected to bring online 886 MMcf/d of takeaway capacity. Mexico City-based Fermaca Services SA de CV is building the pipeline, which runs east to west across central Mexico, across the states of Aguascalientes, San Luis Potosi and Jalisco.

Like several pipeline projects in Mexico, the Aquascalientes pipeline has faced delays. The 290-kilometer (181-mile) pipeline was scheduled to be operational early this year, but the latest information is that it won’t come on stream until the first quarter. BTU expects a delay until mid-year.

In fact, some of the Permian exports to Mexico could eventually come online at the same time as other projects on the U.S. side. Kinder Morgan Texas Pipeline LLC, a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan Inc., is moving forward with its Gulf Coast Express Pipeline, a 1.92 Bcf/d, 42-inch pipeline running from near Waha to Agua Dulce in South Texas near Corpus Christi. The project is one of several being proposed to relieve some of the gas takeaway constraints in the Permian, but in-service dates are also projected to be in 2019 at the earliest.

And if pipeline constraints weren’t enough of an issue, more efficient power plants are also expected to hamper demand growth in supply basins outside the Gulf Coast. Even as around 23 GW of natural gas plants are scheduled to come online in 2018, including 9.2 GW in the Northeast, “new plants are at a 10-15% advantage, and that’s demand destruction” from older plants that have a 7.8 heat rate.

“Over the next couple of years, that’s to the tune of over 1 Bcf/d of demand loss. This is hurting that same area above the arc of pain,” Slingsby said.

Increased power generation from renewables also stands to limit demand growth north of the arc of pain. Over the next few years, BTU sees 4-5 Bcf/d of renewable growth being filled by wind and solar in areas like the Southwest. “This is why we see that need to really cross through the Gulf of Mexico,” Slingsby said, to get to the liquefied natural gas plants.

Until then, the market can expect prices in the supply basins outside of the Gulf Coast to remain weak. On the flip side, Henry Hub would find support from not only growing exports, but also from power demand. With New York Mercantile Exchange futures reflecting sub-$3 throughout the curve, power demand is set to increase.

“A $1 price move from $3.50 to $2.50 results in a cumulative 4 Bcf/d swing in power demand,” Slingsby said.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |