NGI All News Access | Infrastructure

Curtain Closes on Mackenzie Gas Project as Heavyweight Joint Venture Disbands

After 17 years of planning, regulatory ordeals and frustrated rescue attempts, the dormant second incarnation of Canada’s arctic natural gas development has been formally declared dead.

Imperial Oil, Shell Canada, ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil repeated a 40-year-old chapter in foiled northern industry by disbanding their joint venture to build the CDN$16.25-billion (US$13-billion) Mackenzie Gas Project.

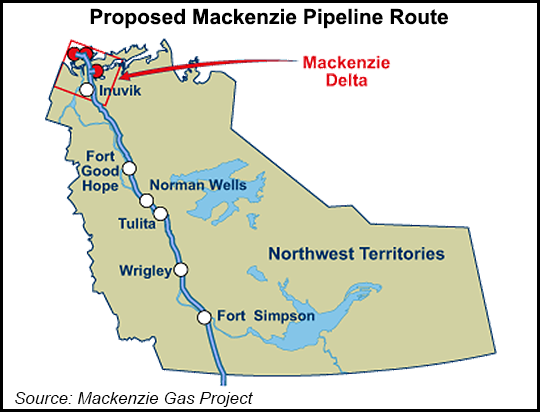

“We recognize this is a disappointing day,” Imperial vice-president Theresa Redburn said in a statement announcing the end of the plan to tap Mackenzie Delta gas and liquid byproducts for delivery via a new 1,200-kilometer (720-mile) pipeline.

“This was a difficult decision,” added ConocoPhillips Canada vice-president Darryl Hass. He thanked “the many organizations and individuals who have advocated for the development of the natural gas resource in the Mackenzie Delta.”

But like the 1977 demise of the first Arctic pipeline project, the 2017 burial was cheered by opponents of frontier industrialization such as Alternatives North, a coalition of Northwest Territories environmental and economic critics.

On both occasions prolonged northern native and southern green resistance tied up industry in a notoriously complex territorial regulatory maze for so long that energy supply and price cycles gutted the economic opportunities that inspired the projects.

In 1977 a federal government inquiry led by British Columbia jurist Thomas Berger imposed a 10-year moratorium against arctic gas development as a time-out to resolve native land claims. Agreements were made with three of the four territorial aboriginal societies, but by the mid-1980s Canada’s gas industry stalled on low prices caused by southern drilling successes that became known as “the surplus that stretched into a sausage.”

When the construction application for the arctic industry reincarnation was filed with the National Energy Board (NEB) in 2004, the 1980s and ”90s surplus was gone, prices were high and a 24-month target was set for completing regulatory approval. Gas market and value trends were projected to be strong enough to support a high cost supply that would start flowing at a rate of 1.2 billion cubic feet per day and eventually top out at 1.9 Bcf/d after pipeline compressor additions.

The NEB finished its share of the review on schedule. But a parallel “joint review panel” that represented a dozen federal, territorial and aboriginal authorities delayed the approval decision until 2011 – long after shale production across the United States and western Canada brought on the current era of abundance and low prices.

As the dissolved venture’s senior partner, Imperial did not disclose total expenditures on the foiled arctic gas project reincarnation. But just one known, minority item in the program highlighted the scale of the industry’s fruitless northern investment.

TransCanada Corp., which showed keen interest in Northwest Territories as well as Alaskan gas development, covered regulatory expenses for an Aboriginal Pipeline Group that was granted a one-third interest in the proposed Mackenzie conduit. The natives received more than CDN$140 million (US$112 million) as a loan that only had to be repaid from their share in toll revenues if the northern pipeline was built.

The second Mackenzie project died on a note of hope that arctic development may yet happen. “Imperial believes the North remains an important potential source of future energy, given the right economic and regulatory conditions,” said Redburn. But the company set no fresh target dates.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |