E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Appalachia Selling Supply Diversity, Petrochem Benefits in Wake of Gulf Coast Storms

As another tropical storm formed in the Caribbean Sea on Thursday and with the effects of Hurricane Harvey still being felt throughout the energy value chain, those working to attract more petrochemical operations to the Appalachian Basin are raising their voices about supply diversity and the region’s other benefits.

“I think we have in the Northeast a window of opportunity right now to get our message out and let people know what our advantages are — the cheapest natural gas prices in the industrialized world, abundant water, closeness to markets, we’ve got a world-class workforce,” said Shale Crescent USA Marketing Director Greg Kozera. Shale Crescent was formed last year by a group of business leaders in the Appalachian Basin to attract global attention and top energy-consuming businesses to the Mid-Ohio Valley, a region near the Ohio River that includes parts of Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania.

“That area is prone to hurricanes. That’s what happens down there,” Kozera said of the vast petrochemical and refining complex along the Gulf Coast. “What Harvey did is remind people that if you’re going to build something on the Gulf Coast, there’s a risk you need to be thinking about. It’s opened up some doors for us to at least get people thinking more about whether they want all their eggs in one basket.”

Kozera and his organization are not alone in their thinking. Sources working in the Appalachian region mourned the disaster and stressed they weren’t being opportunistic. But they also said petrochemical and refined product supply diversity is a topic that has repeatedly come up in the weeks since Harvey made landfall, swamping the Greater Houston area with rainfall and damaging energy infrastructure.

IHS Markit estimated that the damage from Harvey is projected to be between $60-100 billion, which would make it the second most destructive storm on record after Hurricane Katrina. At a damage estimate of $30 billion, Hurricane Irma is expected to rank sixth.

“The area recognizes that we do have a lack of redundancies in the United States,” said NAI Spring’s Bryce Custer, a petrochemical and energy services broker at the commercial real estate firm in Canton, OH. Custer has been working to attract more petrochemical operations to a portion of the Ohio River Corridor that stretches from western Pennsylvania to northern West Virginia.

“For the last year or two, most everybody I’ve been talking to, the common theme is redundancy. Specifically, site redundancy for things like power, product materials and the supplies that are crucial to keep things up and running,” he said.

Slightly more than half of all U.S. refinery capacity is on the Gulf Coast, according to the Energy Information Administration. The region also provides about two-thirds of the nation’s petrochemicals for use in plastics and other manufacturing.

Texas chemical plants declared force majeures, evacuated personnel and endured explosions in the wake of Harvey. But those operations came roaring back to life, with most plants back online within days or weeks of the disaster. They’ve grown increasingly resilient over the years after the lessons learned from past weather events.

“The big difference this time was the amount of water associated with this event,” said Jim Cooper, senior petrochemical adviser at the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers association. Cooper said Gulf Coast petrochemical and refining facilities made extraordinarily quick turnarounds after the hurricane, and he said they’ll likely make further upgrades and buttress preparation processes as a result.

With minimal asset damage, the chemical production sector has been able to recover quickly. But the supply chain is long and inter-dependent. The bottlenecks caused by Harvey are likely to persist into the first quarter of 2018 for propylene and polyethylene supplies that were already tight, according to IHS. That’s likely to push prices up for some chemical products.

While supply diversity isn’t necessarily a critical factor in siting new petrochemical projects, Cooper said, things like feedstock, energy and shipping costs are. Appalachia currently has all those benefits, Custer said, but redundancy has at least made the area and recent discussions “much more interesting. I don’t want to say attractive yet, but it makes it much more interesting.”

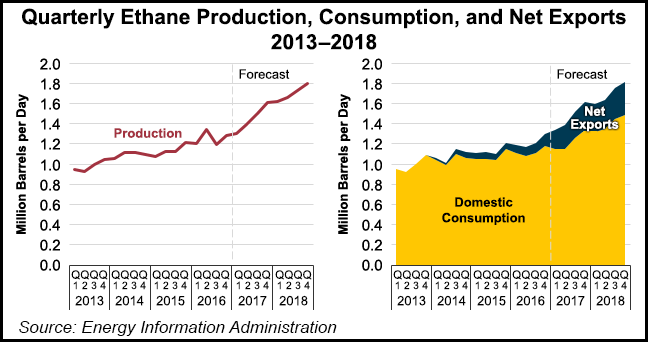

A unit of Royal Dutch Shell plc is currently constructing a multi-billion dollar ethane cracker that would consume about 100,000 b/d in western Pennsylvania to make ethylene and polyethylene. Four other similar facilities have been proposed for the region as well.

Shell has said it decided to build in the region because of the abundant feedstock, market proximity and local support. PTT Global Chemical pcl (PTTGC) spokesman Dan Williamson said the same, adding that the Thailand-based company likes the area for its “low natural disaster risk.” PTTGC is expected to make a final investment decision later this year on a 65,000 b/d ethane cracker it’s proposed for southeast Ohio.

“There’s this dichotomy right now if you look at a map of where all the plastics manufacturers are, they’re all in the Northeast and in population centers around the country,” said Pittsburgh Regional Alliance (PRA) President David Ruppersberger during a panel discussion at the Shale Insight conference last month. The PRA has played a key role to help develop the downstream opportunities the region hopes for with Shell’s cracker and others like that it could be built there.

“If you look at where all the polyethylene pellets are currently produced, it’s literally almost all on the Gulf Coast,” he added. “There’s absolutely an advantage to having a source of polyethylene close to those manufacturers. Recent events in the Gulf have reinforced how critical it is to have alternative sources.”

About 70% of the North American marketplace for polyethylene is within a 700-mile radius of Shell’s site along the Ohio River. The Appalachian region is already home to some of the world’s largest plastics companies, but more plastics converters are expected to come to the area by the time Shell’s cracker enters service in the early 2020s.

Since Shell announced last year that it would move forward with the cracker, local, state and federal officials have stepped up their efforts to overcome a variety of challenges they see standing in the way of petrochemical growth in the region. Good land for large manufacturing operations must be identified, a workforce developed and a storage hub for natural gas liquids is seen as one of the most important factors to any sustained development.

“An Appalachian storage hub would certainly help expand and strengthen the domestic market and improve America’s export capacity,” said Tyler Hernandez, a spokesman for Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV). Capito has introduced legislation that would require federal agencies to study the feasibility of an underground storage hub in Appalachia. Her colleague, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), has also introduced a bill that would make such a hub eligible for funding through the Department of Energy’s loan guarantee program.

Kozera, who travels the country to get the Mid-Ohio Valley’s “open for business” message out, said he sometimes senses hostility from those working on the Gulf Coast about Appalachia’s plan for more petrochemicals. He said it’s as if the message he sometimes receives is “we have the infrastructure, you send us the raw material.”

Kozera doesn’t view it that way. He tries to explain that the regions can complement one another, with Appalachia supporting additional domestic production and the Gulf Coast focusing more on exports to serve a growing global plastics market. He also acknowledges the massive petrochemical expansion that is continuing along the Gulf Coast, with several facilities in various stages of development in Texas and Louisiana.

“We’re not going to overtake the Gulf Coast, it’s just not going to happen,” he said. “All we want are the crumbs to fall off the table. We don’t need 10 or 11 crackers, just build two or three and we’ll be happy as a clam.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |