NGI Archives | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Mexico Unconventional Development Continues to Stall; Auction Round 2.5 Shelved

Mexico’s first auction for shale and other non-conventional sources has been postponed for a second time, reliable sources have told NGI’s Shale Daily.

The auction, Round 2.5, is required to provide a jumpstart for the nation’s production of crude oil and, in particular, natural gas, analysts said. In August, Mexico produced 5.035 Bcf/d, a year/year decline of more than 11%.

The government’s decision to postpone the auction a second time is “on account of electoral considerations,” sources said.

Mexico is due to hold presidential elections next July, and the winner is to take office on Dec. 1, 2018. The Mexican Constitution bars presidents from re-election, so Enrique Pena Nieto, architect of the country’s energy reform, will not be on the ballot.

Already, debate over the prospects for the vote has been heated, and temperatures have been further raised by the recent earthquakes in central and southern Mexico amid squabbles over the reconstruction effort and allegations that corruption helped to facilitate construction permits for buildings that collapsed. So far the death toll from the quakes is at least 363.

The decision to postpone the non-conventionals auction is unfortunate but understandable “in view of the current political noise,” said David Shields, publisher of Energia a Debate. The importance of the auction must not be underestimated, he said. “Mexico’s conventional sources of oil and gas have been going down and they are likely to fall further.

“The only production that’s going up in all of North America is the non-conventional. And if Mexico is to concentrate only on conventional sources, it could be betting on the wrong horse,” Shields said.

However, that’s not likely to be the case in the long run, he added. While time may be running out for the administration, “officials are trying hard to move as fast as possible with the things that they have to do in the limited time left. They are putting all the mechanisms in place for future shale auctions.

“What is most important to the government is not the results in themselves but the mechanisms left in place for future administrations.”

Shale and tight oil and gas production is more quickly turned around using horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing versus conventional drilling. The non-conventional resources could provide a speedy response to the production declines that have beset Mexico in recent years, said Luis Miguel Labardini, a partner in the Mexico City-based consultancy Marcos y Asociados.

“Mexico’s shale resources are the world’s sixth largest,” he said. However, Mexico has a lot of hard work to do before it can realize that potential. “Drilling for shale in Mexico is probably going to be about three times as costly as it is in the United States. We simply don’t have an efficient industry that services wells right now.”

In addition, land rights are different between Mexico and the United States. “In the U.S., royalties are paid directly to the landowners. Here, the royalties go to the state, and the owners receive a very small percentage.” Companies likely are going to opt to buy up big tracts of land when they want to drill for shale/tight resources to achieve economies of scale, he said.

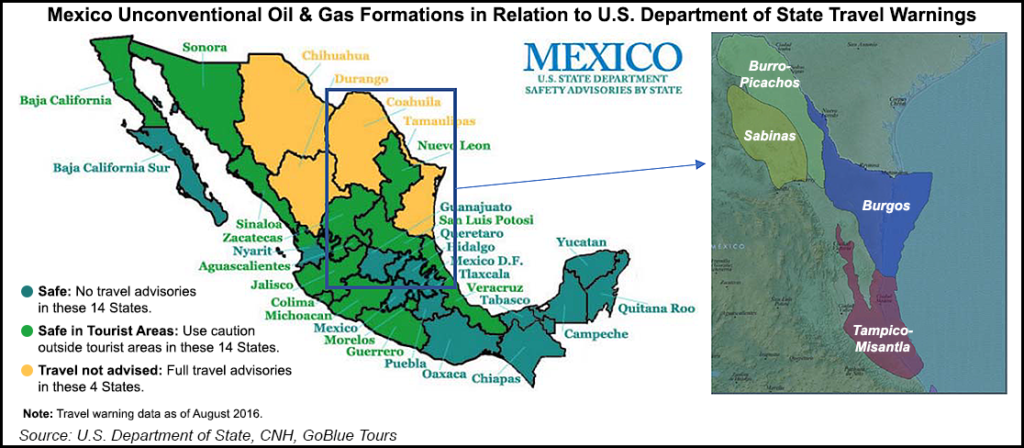

Other problems could be on the horizon. “The Mexican basin with the highest potential for shale is Tampico-Misantla,” Labardini said. “And it’s in a zone where there are social conflicts and high crime rates. Security costs that can’t be underestimated. It’s all very complicated.”

Tampico-Misantla, on the Gulf Coast, extends across the states of Veracruz and Tamaulipas, both of which are beset by narco-violence. The basin, which extends into the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico, may be one of 24 global onshore “super basins,” much like the Permian Basin with its myriad reservoirs and multiple source rocks, according to IHS Markit.

The growing volume of natural gas imports from the United States is giving cause for concern for officials such as Energy Secretary Pedro Joaquin Coldwell and Juan Carlos Zepeda, president of the National Hydrocarbons Commission.

“But the only way we can stem the flow of the imports is by producing shale gas in large volumes and with prices that are competitive,” Labardini said.

An auction of shale and other non-conventional sources was originally slated in the Round One series of upstream tenders, the first in Mexico since the 2013-2014 energy reform that ended the state monopoly founded in 1938. It was postponed in Round One because the regulatory framework for drilling techniques such as fracturing was not yet ready, and because of low commodity prices.

The new regulations, including legislation on the use of water, were ready for the recently concluded Round Two. However, last week the first announcements for Round Three began with no mention of the non-conventionals auction for Round Two.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |