Regulatory | NGI All News Access

California Bill Would Eliminate Fossil Fuels for Power by 2045

In a state already wielding some of the most aggressive climate change measures anywhere, California lawmakers are considering a measure (SB 100) that would phase out the use of natural gas for electric generation by 2045.

With the state legislature headed toward adjournment Sept. 15 and no committee hearings in the final two weeks of the session, it is unclear whether the measure, supported by the Senate leadership, will get to Gov. Jerry Brown’s desk this year. Two years ago he signed into a law a measure setting a 50% renewable goal for the state’s power supplies by 2030.

SB 100 passed out of the California Senate in May and is awaiting action in the lower house Assembly. One veteran energy lobbyist in Sacramento told NGI that there is always a chance of eleventh-hour passage, but “there are a lot of pieces very much up in the air.”

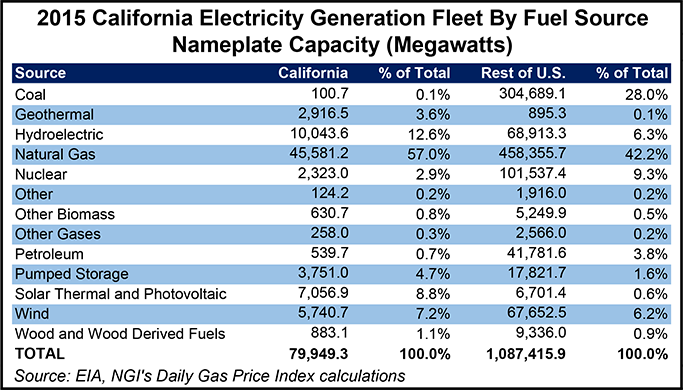

With gas providing more than a third of the state’s power supplies last year and representing more than half the 70,000 MW of generation capacity available to the state grid operator, proponents maintain it will continue to have role, particularly in providing a backup to intermittent renewable sources such as solar and wind. Houston-based Calpine Corp., which operates 20 gas-fired generation plants in the state, maintains that gas use for power will stick around.

Last year 29% of California’s power came from renewables, with natural gas providing about 40%. Under SB 100 that would shift to 60% renewables and 40% from nonfossil fuels, including energy efficiency, battery storage and other passive programs).

Some energy think tank analysts in the state have confirmed the push for 100% renewables is technically do-able, but they caution that it is still unprecedented and an “ongoing experiment.” Others worry about the implications for grid reliability and the need to coordinate more closely with adjacent states and power jurisdictions.

Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (PG&E) has a pending proposal to phase out the state’s last major nuclear generating plant at Diablo Canyon along the central California coast by 2025 and deemphasize gas-fired generation, depending more on its massive hydroelectric system and other sources.

In mid-2016, the giant combination utility unveiled plans to eventually close the 2,200 MW nuclear plant, the state’s last, and it subsequently told the California Public Utilities Commission that it would increase the utility’s future investment in energy efficiency, renewables and storage beyond current state mandates in those areas.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |