Markets | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Global Natural Gas Output, Demand Stall in 2016 on Weak Growth, Price Challenges, Says BP

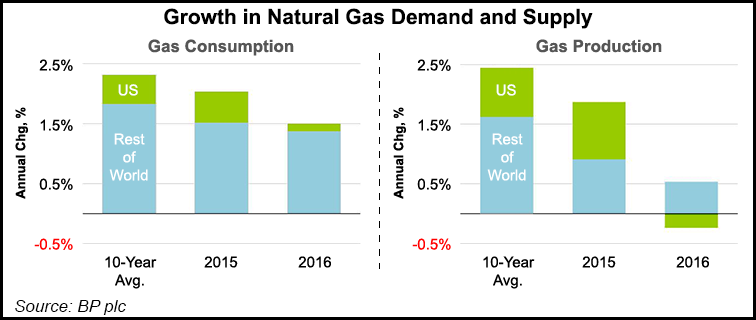

Natural gas demand worldwide rose by only 1.5% last year, slower than the 10-year average, while production climbed a mere 0.3%, the weakest growth in almost 34 years, with U.S. output falling for the first time since the shale revolution, BP plc said Tuesday.

The 2017 edition of the benchmark “BP Statistical Review of World Energy,” the oil major’s 66th annual edition, found a long-term transition underway as the world’s operators also adapt to nearer-term oil and gas price challenges. The data “clearly” demonstrates market transitions underway, with a shift to slower growth in global energy demand, demand sharply moving toward the developing economies of Asia, and a marked shift toward lower carbon fuels as renewables grow and coal use plunges.

The “longer-term trends we can see in this data are changing the patterns of demand and the mix of supply as the world works to meet the challenge of supplying the energy it needs while also reducing carbon emissions,” said BP Group CEO Bob Dudley, who introduced the report. “At the same time, markets are responding to shorter-run run factors, most notably the oversupply that has weighed on oil prices for the past three years.”

Overall, global energy demand was up only 1% from 2015, a rate similar to the previous two years but below the 10-year average of 1.8%, Chief Economist Spencer Dale said during a press briefing from London.

“This is a third year where we’ve seen weak growth in world energy demand,” he said. “The new normal is that all of this growth is coming from developing economies,” mostly China and India.

Specifically for global gas, consumption was slower than than 10-year average rate of 2.3%, with production essentially flat (0.3%) year/year, the weakest growth in more than three decades, other than in the immediate aftermath of the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

‘Lackluster’ U.S. Supply Performance

“This sub-par growth went hand-in-hand with falling gas prices,” Dale said. “Henry Hub prices were 5% lower than in 2015, European and Asian gas markers were down 20-30% as prices continued to adjust” to increased liquefied natural gas (LNG) supplies.

“Much of the lackluster performance can be traced back to the U.S., particularly on the supply side, where falls in gas and oil prices caused U.S. gas production to fall for the first time since the U.S. shale gas revolution started in earnest in the mid-2000s.”

U.S. gas production fell by an estimated 2.5% from 2015, down 17 billion cubic meters (bcm), he said.

Beyond the United States on the demand side, gas consumption in Europe rose strongly, up 6%, or 28 bcm, helped by both the increasing competitiveness of gas relative to coal and weakness in European nuclear and renewable energy. The Middle East (3.5%, 19 bcm) and China (7.7%, 16 bcm) recorded strong increases, aided by improving infrastructure and availability of gas. The largest declines year/year were in Russia (down 3.2%, 12 bcm) and Brazil (down 12.5%, 5 bcm), both of which benefited from gains in hydropower.

On the gas supply side, Australian production, rising 25.2% or 19 bcm, “was the standout performer as several new LNG facilities came onstream,” Dale said.

“Looking at the growing market for LNG, although China continued to provide the main source of growth, it’s striking that the increasing availability of supplies has prompted a number of new countries, including Egypt, Pakistan and Poland, to enter the market in the last year or two. These new entrants were helped by the increased flexibility afforded by plentiful supplies of floating storage and regasification units,” aka FSRUs.

Last year was the first to see the “growth spurt we expect to see in LNG, with global supplies set to increase by around a further 30% by 2020,” Dale said. “That is equivalent to a new LNG train coming onstream every two-to-three months for the next four years — quite astonishing growth.”

LNG Trade Becoming More Flexible

As LNG trade grows, the global gas markets likely will evolve “quite materially,” a view held by BP economists for several years.

“Alongside increasing market integration, we are likely to see a shift toward a more flexible style of trading, supported by a deeper, more competitive market structure,” Dale said. “Indeed, this shift is already apparent, with a move toward smaller and shorter contracts and an increase in the proportion of LNG trade, which is not contracted and is freely traded.”

Europe’s thirst for LNG is a prime example, according to Dale.

“On the one hand, Europe’s large and increasing need for imported gas, combined with its relatively central location amongst several major LNG suppliers, means Europe is often highlighted as a natural growth market for LNG. On the other hand, Europe’s access to plentiful supplies of pipeline gas, particularly from Russia, means LNG imports are likely to face stiff competition.

“In terms of this battle of competing supplies, Round 1 went to pipeline gas. Europe’s gas imports increased markedly last year, reflecting the strong increase in demand, together with weakness in the domestic production of natural gas. But virtually the entire rise in European imports was met by pipeline gas, from a combination of Algerian and Russian supplies, with imports of LNG barely increasing.”

Said Dale, “The economic incentives in this battle of competing supplies are clear.” Similar to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) response to surging U.S. tight oil supply, “Russia has a strong incentive to compete to maintain its market share in the face of growing competition from LNG supplies.”

However, the competition is complicated by concerns that Europe could become overly dependent on a single source of supply, giving rise to energy security issues.

“The interesting question is whether the growth of global LNG trade, by fostering a more globally integrated gas market, with the optionality of being able to turn to LNG should the need arise, might mitigate those concerns,” Dale said. “Europe doesn’t need to consume large amounts of LNG imports in ‘normal’ times, but it has the option of doing so if the need arises.”

Oil demand grew at the fastest annual rate among fossil fuels in 2016, up 1.6%, as low crude prices boosted consumption. However, oil production was up by only .5%, or around 400,000 b/d, the lowest increase since 2009, as producers slashed spending.

U.S. Tight Oil ‘Like a Weeble’

U.S. tight oil output was down dramatically from 2015, but it has rebounded in recent months, a factor that the market should acknowledge, Dale said.

“U.S. tight oil is like a Weeble,” he said, referring to the roly-poly toys originated by Hasbro’s Playskool line. “It falls off, but then it bounces back up again. Any sense of trying to kill tight oil makes no sense,” he said, in reference to OPEC efforts to crush domestic supply by raising cartel output as prices began to fall in late 2014. OPEC since has retrenched, with plans to reduce overall output through next March.

Renewables were again the fastest growing of all energy sources, rising by 12% year/year. Although still providing only 4% of total primary energy, renewables growth represented almost a third of the total growth in energy demand in 2016. In contrast, use of coal, the most carbon-intensive of the fossil fuels, fell steeply for a second year, down by 1.7%, primarily because of declining demand from the United States and China.

The combination of weak energy demand growth and the shifting fuel mix meant that global carbon emissions are estimated to have grown by only 0.1% — making 2016 the third consecutive year of flat or falling emissions. Last year also marked the lowest three-year average for emissions growth since 1981-1983.

“While welcome, it is not yet clear how much of this break from the past is structural and will persist,” Dudley said about the decline in carbon emissions. “We need to keep up our focus and efforts on reducing carbon emissions.”

As Dudley has stressed before, he said BP “supports the aims” set by the Paris agreement, reached in late 2015 by more than 190 countries. BP “is committed to playing our part to help achieve them.” The Trump administration recently announced it intends to withdraw the United States from the voluntary global pact.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |