Expectations High for California Hydropower, Less Gas-Fired Generation

California power grid officials will not make it official until April, but state energy regulators and large consumers are expecting a deluge of cheap hydroelectric supplies this spring and summer, although there are still factors that could dampen the full unfolding of that scenario after five years of sub-normal water power due to the region’s prolonged drought.

While academicians and other analysts have estimated that during the 2011-2016 drought Californians paid as much as $2 billion more for electricity, and greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector increased 10%, everyone is predicting increased hydropower this year in the wake of record rain and snowpack levels.

At least for the summer peak, increased hydroelectric supplies are expected, a spokesperson for the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) said in a recent Los Angeles Times report. In 2011, hydropower accounted for 18% of in-state generation, compared with 5.9% in 2015, during the drought.

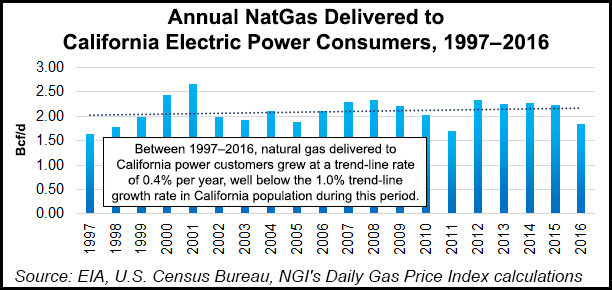

Natural gas-fired generation is expected to decline after remaining steadily at about 60% of the state’s generation for the past five years, but some of that drop relates to continued improvements in efficiency at gas-fired generation plants, a California Energy Commission (CEC) spokesperson told NGI.

“Over the 2001-15 period, California’s systemwide thermal efficiency for natural gas power plants improved by 23%,” thanks to “the successful development of technologically advanced combined-cycle plants,” the spokesperson said.

CEC officials are not making any official predictions yet about the amount of hydroelectric power they expect this year.

“A comparison of hydro to natural gas has lots of factors to consider,” the spokesperson said. “In 2012, natural gas use for generation went up while hydro and nuclear fell; [Southern California Edison Co.’s] San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station stopped producing electricity in 2012, so while hydro continued to fall in the following years, natural gas has stayed steady.”

Renewable generation, which used to trail both hydro and nuclear generation, began providing more generation than the two other sources combined in 2015.

“Because the primary purpose of the state’s series of water reservoirs is flood control, not hydroelectric generation, the amount of generation cannot be estimated until flood control releases cease,” the spokesperson said.

“However, using ‘wet’ hydroelectric years, such as 2006 and 2011, this year’s hydroelectric generation could be 40,000 to 50,000 GWh, or about 21% of in-state generation. In 2015, in-state hydro electric generation was about 13,000 GWh, or 7% of the in-state generation.”

A 2015 analysis by the CEC found that in the first 15 years of the century, California’s portfolio of non-cogeneration gas-fired power plants generated 29% more energy using the same amount of natural gas as 14 years earlier.

Underscoring this, average annual heat rates for California’s gas-fired power plants have gone down steadily, from more than 10,000 in 2001 to 7,760 in 2014, according to the CEC report.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |