Regulatory | NGI All News Access

USGS: Ground Shook Less in Oklahoma Last Year, But Hazards Remain

Seismic activity thought to be caused by human actions — mainly drilling wastewater injection — declined in Oklahoma last year, possibly because of limits placed on disposal wells, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) said Wednesday.

Between 1980 and 2000, Oklahoma averaged about two earthquakes greater than or equal to magnitude 2.7 per year, according to USGS. However, the number jumped to about 2,500 in 2014 and 4,000 in 2015.

But then it dropped to 2,500 in 2016.

“The decline in 2016 may be due in part to injection restrictions implemented by the state officials,” USGS said. “Of the earthquakes last year, 21 were greater than magnitude 4.0 and three were greater than magnitude 5.0.”

USGS considers a magnitude 2.7 earthquake to be the level at which ground shaking can be felt. An earthquake of magnitude 4.0 or greater can cause minor or more significant damage.

The forecasted chance of damaging ground shaking in central Oklahoma is similar to that of natural earthquakes in high-hazard areas of California.

“Most of the damage we forecast will be cracking of plaster or unreinforced masonry. However, stronger ground shaking could also occur in some areas, which could cause more significant damage,” said Mark Petersen, chief of the USGS National Seismic Hazard Mapping Project.

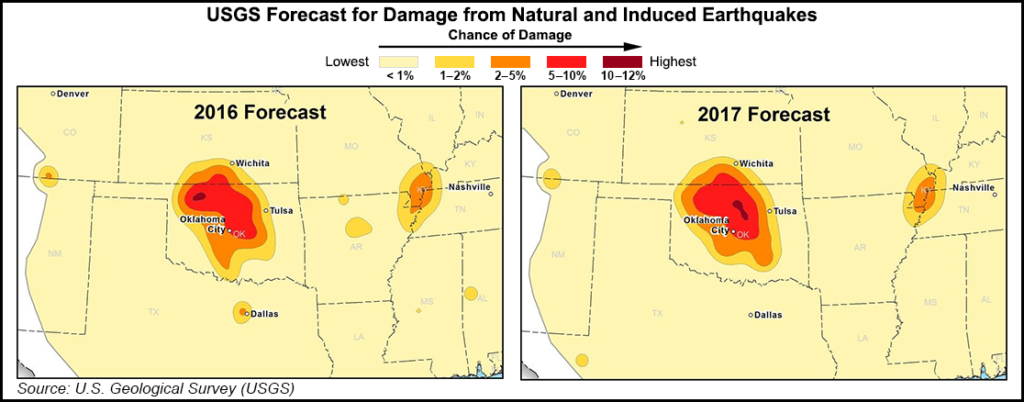

USGS on Wednesday released new maps identifying potential ground-shaking hazards in 2017 from both human-induced and natural earthquakes in the central and eastern United States (CEUS). This is the second consecutive year both types of hazards were forecasted. The research was published in Seismological Research Letters.

About 3.5 million people live and work in areas of the CEUS with significant potential for damaging shaking from induced seismicity in 2017. The majority of this population is in Oklahoma and southern Kansas, USGS said.

Another 500,000 people in the CEUS face a significant chance of damage from natural earthquakes in 2017, which brings the total number of people at high risk from both natural and human-induced earthquakes to about 4 million, USGS said.

“The good news is that the overall seismic hazard for this year is lower than in the 2016 forecast, but despite this decrease, there is still a significant likelihood for damaging ground shaking in the CEUS in the year ahead,” Petersen said.

The 2017 forecast decreased compared to last year because fewer felt earthquakes occurred in 2016 than in 2015. This may be due to a decrease in wastewater injection resulting from regulatory actions and/or from a decrease in oil and natural gas production because of lower commodity prices, USGS said.

Despite the decrease in the overall number of earthquakes last year, Oklahoma experienced thelargest earthquake ever recorded in the state as well as the greatest number of large earthquakes compared to any prior year. Furthermore, the chance of damage from induced earthquakes will continue to fluctuate depending on policy and energy industry decisions, Petersen said.

“The forecast for induced and natural earthquakes in 2017 is hundreds of times higher than before induced seismicity rates rapidly increased around 2008,” Petersen said. “Millions still face a significant chance of experiencing damaging earthquakes, and this could increase or decrease with industry practices, which are difficult to anticipate.”

The USGS maps indicate an especially high ground-shaking hazard in five areas of the CEUS in 2017. These same areas were identified in the 2016 forecast. Induced seismicity poses the highest hazard in two areas: Oklahoma/southern Kansas and the Colorado/New Mexico area known as the Raton Basin.

Enhanced hazard from induced seismicity was also found in Texas and north Arkansas, but the levels are significantly lower in these regions than those forecasted for 2016. While earthquakes are still a concern, scientists did not observe significant activity in the past year, so the forecasted hazard is lower in 2017, USGS said.

“The 2016 forecast was quite accurate in assessing hazardous areas, especially in Oklahoma,” Petersen said. “Significant damage was experienced in Oklahoma during the past year as was forecasted in the 2016 model. However, the significantly decreased number of earthquakes in North Texas and Arkansas was not expected, and this was likely due to a decline in injection activity.”

The Oklahoma Corporation Commission Oil and Gas Conservation Division (OGCD), which regulates oil and gas activity; and the Oklahoma Geological Survey said the USGS findings validate the work done to address induced seismicity in the state.

“To date, directives issued by the OGCD have reduced oil and gas wastewater disposal into the Arbuckle formation in the 15,000-square-mile earthquake area of interest in Oklahoma by more than 800,000 barrels a day and removed the potential for about two million barrels a day in future disposal,” they said.

To determine whether particular clusters of earthquakes were natural or induced, the USGS relied on published literature and discussions with state officials and the scientific and earthquake engineering community. Scientists looked at factors such as whether an earthquake occurred near a wastewater disposal well and whether the well was active during the time the earthquakes occurred. If so, it was classified as an induced event.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |