Western Canada Oilsands Writedown Sinks ExxonMobil Reserves in 2016

ExxonMobil Corp. recorded a 19.3% reduction in its proved reserves in 2016, its steepest reduction ever, erasing almost 3.3 billion boe to end the year at under 20 billion boe. Only 65% of production was replaced last year, marking the second year in a row the supermajor failed to fully replace its output.

Until 2015, ExxonMobil had for more than 20 years replaced 100% of the reserves it produced. The writedown of the entire 3.5 billion bbl of proved undeveloped reserves, or PUDs, at the Kearl oilsands development in Western Canada was responsible for nearly all of last year’s reserves losses, the Irving, TX-based supermajor said Wednesday.

Domestic producers under U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules are required to use the 12-month average trailing price for oil and natural gas to book the value of reserves. The commission also mandates that PUDs be developed within five years or be deleted from the booked numbers.

“As a result of very low prices during 2016, certain quantities of liquids and natural gas no longer qualified as proved reserves under SEC guidelines,” the supermajor said in an annual Form 10-K filing with the SEC. Besides the oilsands writedown, another 800 million boe in North America oil and gas bookings did not qualify as proved, mainly because of the “acceleration of the projected economic end-of-field life.”

The revisions are not expected to “affect the operation of the underlying projects or to alter the company’s outlook for future production volumes.”

ExxonMobil had signaledin October and againin January that proved reserves revisions for 2016 were likely. For 4Q2016, the company recorded a $2 billion writedown on the value of U.S. natural gas fields.

The 19% reduction to the value of its 2016 proved reserves is the largest since ExxonMobil was formed in 1999. The writedown pushed the bookings to the lowest level since 1997, according to an analysis by Bloomberg. The previous record by ExxonMobil was a 3% reduction to proved reserves taken during the global financial downturn in 2008.

ExxonMobil added 1 billion boe of reserves last year in the United States, Kazakhstan, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Norway, but it replaced only 65% of production. During 2015, ExxonMobil also added an estimated 1 billion boe of proved reserves, but it replaced just 67% of output.

“There are two ways to grow reserves — through the drillbit, and via acquisitions,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of strategy and research. “The bigger and bigger you get, the harder it is to grow reserves by drilling, everything else being equal. It just gets harder and harder to grow from a larger base. It’s not like ExxonMobil isn’t doing anything to grow its reserves organically, but for extremely large producers, acquisitions will always be a necessary evil.”

Sometimes, though, acquisitions may end up being poorly timed or overpriced. Some analysts claimed ExxonMobil overpaid in 2009 for onshore natural gas heavyweight XTO Energy Inc.

However, the company “has the strong balance sheet and deep pockets” to absorb acquisitions that fit within its long-term strategy, Rau said. ExxonMobil holds a long-term view that natural gas will continue to gain global share.

“Moreover, their cash balance gives them a huge advantage in purchasing distressed assets,” Rau said. If the company did nothing “but manage the business to maximize cash flow during upturns and buy reserves on the cheap during downturns, it can do quite well.”

And ExxonMobil has done “quite well,” he said. “According to Bloomberg data, between 2000 and 2015, the company generated an average return on invested capital of 16%, versus an average weighted average cost of capital of just 9.2%. That is phenomenal.

“Oil and gas producers get maligned for not creating long-term, full-cycle value, but many companies over all other industries would do backflips if they earned those kind of returns.”

The company said last year it added nearly 2.5 billion boe to the resource base “by-the-bit,” or organically, through exploration discoveries, undeveloped resource additions and strategic acquisitions.

Unconventional resource additions were made in the Appalachian Basin in Pennsylvania, the Permian Basin in West Texas and Neuquen province in Argentina, ExxonMobil noted. Overall, the corporation’s resource base totaled more than 91 billion boe at year-end 2016, taking into account field revisions, production and asset sales.

Oilsands are among the most costly types of energy projects because of their remote location and because the extracted raw bitumen undergoes expensive processing to convert it into a thick synthetic crude. ExxonMobil also is not the only oilsands producer slammed by reserves reductions. Houston-based ConocoPhillips also said it would remove 1.15 billion boe of oilsands from its 2016 reserves bookings, a 21% cut that pushed reserves numbers to a 15-year low.

“Prices to date in 2017 have been higher than the average first-of-month prices in 2016,” ExxonMobil noted. “Among the factors that would result in these amounts being recognized again as proved reserves at some point in the future are a recovery in average price levels, a further decline in costs, and/or operating efficiencies.”

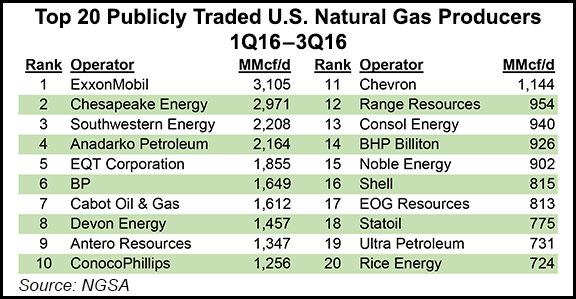

Over the past 10 years, ExxonMobil said it has added proved oil and gas reserves totaling 13 billion boe, including the impact of asset sales, and it has replaced 8% of produced volumes. Reserves life at current production rates is 13 years, with liquids accounting for 53% of proved reserves. ExxonMobil remains the top North American natural gas producer, and it also continues to make significant investments in the U.S. onshore. Last month it struck a deal valued at close to $6.6 billion with the Bass family of Fort Worth, TX, which more than doubled its Permian Basin resource base.

Meanwhile, ExxonMobil remains under scrutiny by the SEC and New York Attorney GeneralEric Schneiderman, with separate probes into how it values its proved reserves portfolio.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |