Markets | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Global LNG Demand Quietly Matching Supply as More Players Join Game, Says Shell Exec

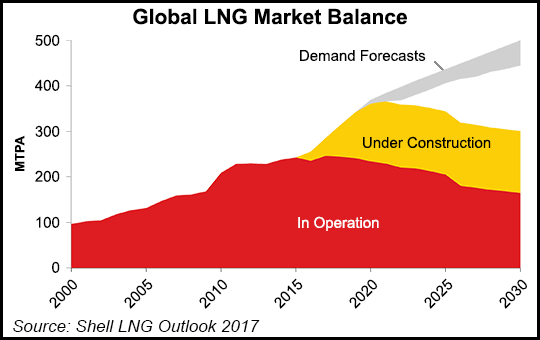

Worldwide liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply appeared to swamp demand in 2016 as new capacity came online, but big buyers snapped up more cargoes and new participants emerged, basically evening out the supply-demand picture, according to Royal Dutch Shell plc.

The supermajor, one of the world’s largest gas producers and LNG operators, recently published its first Shell Global LNG Outlook, continuing a tradition begun by BG Group plc, which Shell took over last year. Former BG executive Steve Hill, now Shell’s executive vice president for the gas and energy marketing trading arm, said LNG supply and demand is strong well into the 2020s.

“We see strong growth in LNG supply for the rest of the decade…but we also see a very positive outlook for demand, driven by a strong outlook for gas demand growth, driven by gross domestic product growth, favorable policy and gas’ role in decarbonization and being part of the solution.”

LNG Demand Twice NatGas Consumption

Global demand for LNG reached 265 million metric tons (mmt) in 2016, including an increase in net LNG imports of 17 mmt, according to Shell. What’s driving the growth in LNG is growth in demand that is twice the rate of worldwide natural gas consumption.

“We see particularly strong demand for LNG, 4-5% a year compared to 2% for gas, and that’s driven by the gas demand growth combined with LNG’s role in replacing declining domestic gas supplies in certain markets, which has been unlocked by floating regas technology,” Hill said. “We also see the introduction of new demand sectors for LNG, in the transportation sector and small-scale LNG.

Reports that LNG supply sources swamped demand last year were overblown, Hill said. In fact, there “clearly wasn’t any evidence of an oversupply.” Unlike the ballyhooed supply projects touting big investments, big construction projects and lots of press, LNG demand has grown more subtly and has quietly infiltrated more diverse markets, Hill said.

Why did so many experts highlight the oversupply in 2016?

“We think the reason for that is, supply growth is very visible,” Hill said. “Supply growth tends to come from new LNG projects, which typically cost $10 billion, their sanctions are well publicized, their construction is well publicized, they take four to five years to build. It’s very, very easy to see new supply coming to the market and easy to predict the overall LNG supply volumes five years ahead.

“Demand growth is much less visible. Demand infrastructure typically operates at a much lower utilization than supply infrastructure so when demand grows, you don’t necessarily see infrastructure investments to demonstrate that growth.” When new LNG markets are created today, “they’re mostly created using floating regas technology,” infrastructure that can be put in place in less than a year. Demand growth is under the radar and can happen “very quickly.”

Prices Point to Balanced Market

Another tell about how balanced the LNG market was in 2016 relates to pricing. Spot LNG prices worldwide over the past two years have risen during the winter when demand has been highest and declined as weather improved. If the LNG market had been oversupplied last year, “we would have expected a reduction in LNG price in relation to other commodities,” Hill said. “And that didn’t happen. We see this as a very strong sign that we have a balanced market.”

China and India were the two “fastest growing buyers last year,” a trend that should continue. The countries combined increased their imports in 2016 by a combined 11.9 mmt, boosting China to 27 mmt and India to 20 mmt.

As well, six new importing countries have joined the gas import mix since 2015: Colombia, Egypt, Jamaica, Jordan, Pakistan and Poland. Remarkably, Egypt, Jordan and Pakistan last year have become the fastest growing LNG importers in the world. The countries already have extensive gas infrastructure in place, but because of local shortages, the countries combined imported 13.9 mmt. Since 2000, the number of LNG importers has risen to 35 from about 10, and the import figure is expected to expand.

According to Hill, “two stories emerged last year” in terms of LNG demand. China and India had “very large growth, because of the overall growth in energy demand in those markets and increased gas concentration. New markets also grew rapidly, including in Egypt, Pakistan and Jordan, markets where the gas industry is established but declining domestic production is creating a hole.

“Once you tap into the market, with a floating regas unit, we are able to supply existing gas customers and existing gas demand through existing infrastructure.” These markets don’t rely on overall gas demand growth, they simply need to see replacements through LNG, he said.

Last year there was a reduction in LNG demand in some regions, including Brazil and Japan. Brazil, whose primary power source is hydroelectric, saw its gas demand decline last year because it had abundant rainfall. Japan reduced its gas demand after restarting some nuclear power plants. The UK and Belgium also reduced their LNG imports last year, “but even though the imports were lower, we see that as a sign of strength in the LNG market because the way the LNG market works at the moment, Northern Europe tends to be the balancing market.”

‘Difficult to Decarbonize’ Sector Growth

Renewables are expanding at a fast clip, but the world’s thirst for natural gas, and it’s ability to partner with renewables, has become a key issue for countries attempting to grow while addressing environmental concerns, Hill said.

“About half of the expected growth in gas demand is expected to come from the power sector…because gas is uniquely suited to complement renewables and solve the intermittency issue and provide reliable power when it’s not sunny and it’s not windy…

“But probably more interestingly, we expect that over half of the gas demand to come from other difficult to decarbonize sectors, where gas is clearly the cleanest energy source.”

Growth is coming from “a combination of industry, where there are some high temperature applications, like steel production, where gas is simply more suited than electricity.” It’s also rising in the heating sector. “It’s going to be a long time before renewables provides the solution to heat Beijing or Moscow or Seoul in the winter. And increasingly in the future, it will be in the transport sector.”

Global governments and other policymakers also recognize the environmental benefits of gas as well, which in turn has created policies that are favorable to gas demand, he said. In the shipping industry, for example, the sulfur specification for fuel oil has been reduced from 3.5% sulfur to .5% sulfur by 2020.

“That means that the current shipping brokering of choice today, fuel oil, will no longer be an option without technological changes to the shipping and the introduction of bunkers and introduction of scrubbers,” Hill said. “Therefore, to meet the new specification, ship owners will need to look at alternative fuels, such as diesel, low-sulfur fuel oil and LNG. And that clearly makes LNG more competitive in that space.

“Secondly, when we look at China, which is the market that has the biggest potential growth for LNG, we see government policies both supporting increased gas consumption and reducing the utilization of coal, both in the industrial sector and more recently in the power sector. China has suspended plans for more than 100 coal-fired power plants that were either approved or already under construction.”

LNG in the transport sector, i.e. road and marine, is a positive wildcard for demand too, Hill said. “Cars can easily be electrified,” but not so heavy transport, where “batteries simply won’t do because of the weight of the machinery, the distances to be traveled. It’s mostly trucking, it’s also mining equipment, it’s building equipment, it’s the real heavy duty land transport sector,” where gas demand is rising around the world.

In the marine transport sector, where mostly heavy fuel oil today is the power source, “we see a lot more interest in LNG in this space, initially for cruise liners but then through container ships,” Hill said. “Therefore, while the estimates for LNG demand in the transport sector are material already, there is obviously considerable potential upside from those levels.”

LNG is unlikely to become a big source of transport fuel in North America anytime soon, however. “In the U.S., we expect the LNG for transport volumes to be relatively small compared to overall size of U.S. gas demand,” Hill said.

Shell’s Thesis Supported

Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH) analysts said Friday new global data supports Shell’s bullish thesis.

“January import data (admittedly buoyed by a cold winter) would also support Shell’s thesis,” TPH analysts said. “China’s LNG imports were plus-40% year/year (y/y) at 3.4 mmt,” which continued from a record 3.7 mmt in December. Meanwhile, Japan was up 15% y/y to 8.3 mmt, or 6.7% month/month (m/m), while Indian imports, even though they were down 15% m/m at 1.2 mmt, still have risen 16% since April 2016.

TPH analysts noted that Woodside Petroleum announced it would expand its Pluto LNG facility in Australia, while Noble Energy Inc. pulled the trigger on its Leviathan gas project offshore Israel. Thailand’s PTTEP also agreed to invest “$15.5 billion to boost LNG capacity four-fold to 19 mmta by 2023, and Chile where Enagas will spend $300 million to expand its LNG import facility by 2021. Another potential boost for LNG came from the Panama Canal’s environmental initiatives for shippers to priority points for LNG-fueled ships,” TPH said.

Societe Generale in arecent report said liquefaction capacity worldwide could accelerate by 10%/year between 2016 and 2020 from 2% annual growth from 2010-2015. According to BP plc’s 2017annual energy forecast, LNG supplies should account for more than half of traded gas by 2035, with one-third of the growth over the next four years as a series of projects come onstream. ExxonMobil Corp. in its latest annual energy outlook in December also predicted strong growth for gas and gas exports, with North America the largest gas exporter by 2040.

According to Shell, LNG prices are expected to continue to be determined by” multiple factors, including oil prices, global LNG supply and demand dynamics and the costs of new LNG facilities. In addition, the growth of LNG trade has evolved into helping meet demand when domestic gas markets face supply shortages.” The trade also is evolving to meet the needs of buyers, including “shorter-term and lower-volume contracts with greater degrees of flexibility. Some emerging LNG buyers have more challenging credit ratings than traditional buyers.”

Shell has a “positive view on LNG demand,” and therefore, on long-term prices, Hill said.

Flexible Pricing Options

“There are more pricing options that are available to buyers. If a buyer wants to buy from Shell on an oil index, we will sell to them. If they want to buy at Henry Hub index, we will sell to them. If they want to buy a hybrid, we will sell to them. If they want to buy spot cargoes at a spot price, we will sell to them.”

Buyers have lots of choices today, said the Shell executive. “We’ve clearly moved away from the world where all LNG is sold into long-term contracts and they are all oil indexed. We don’t really seem to be as an industry coalescing on a new structure where everything is priced in the same way yet. We have a suite of choices of pricing constructs for buyers and I think that’s actually what buyers are asking for.”

Moody’s Investors Service, in a report published after Shell’s forecast, said it expects LNG prices to remain constrained beyond 2020 as new supply capacity comes online and demand from large importers declines. However, it also sees demand growing.

“Strong LNG demand growth from China, India and new markets will not be enough to absorb the fresh supply capacity coming online, particularly with demand falling in the largest importing countries, Japan and Korea,” said Moody’s senior credit officer Tomas O’Loughlin. “The market will not rebalance until the early years of the next decade, when global demand and LNG import infrastructure catches up with supply.”

According to Moody’s, global oversupply will peak in 2019 at about 55 mmty, and over this period, significant U.S. volumes could head to Europe. Boosted by low gas prices, as well as environmental concerns, LNG demand is expected to grow, leading to more infrastructure buildout. Until the market rebalances, “investment returns for developers of Australian projects will be weak, and U.S. LNG offtakers will find it difficult to recover all of their liquefaction costs,” O’Loughlin said.

FIDs Can Wait

The industry has been flexible in developing new gas demand, but final investment decisions (FID) have decreased. Shell and its partners last year indefinitely shelved FIDs for two North American LNG projects, one planned in Lake Charles, LA, and the other to be built in Kitimat, BC, LNG Canada.

But after 2020, “we believe the industry needs more LNG supply, and therefore, more projects to be sanctioned to meet continued growth in demand,” Hill said. “We’re big believers in this business, and we’re very excited about the position we have in this business. We have said we aren’t planning to do any FIDs this year; that’s not going to change.

“Clearly, the market will need new LNG supply sometime after the turn of the decade, and therefore, clearly new investments will be required. And Shell would expect to be one of the companies that are making those investments.”

The company “is fortunate to have several projects that we believe will be competitive projects in our portfolio that we would be able to sanction at some stage. I think the industry is really taking advantage in the current hiatus for FIDs to really focus on making sure we really optimize the cost structure of new LNG projects. For any FID Shell makes, we will absolutely want to be sure we are at the low end of the cost curve to make sure we have competitive projects going forward. As to which projects we do next and when we do it…we have a lot of excitement talking about it, but we haven’t come to a conclusion yet.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |