E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S., Canada Shale Development Still Leaving Global Competitors In Dust, Says Raymond James

The United States and Canada may hold less than one-fifth of the world’s shale resources, but combined they produce nearly all of the shale natural gas and oil, and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon, Raymond James & Associates Inc. said Monday.

Other countries outside of the United States and Canada began testing their unconventional formations once the North American revolution got underway, but the results remain mixed at best, said analysts Pavel Molchanov and Jean-Pierre Dmirdjian.

“There is no doubt that shale resources are present in massive quantities worldwide, but the tricky aspect of the emerging plays will be how to achieve cost-effective scale-up, bearing in mind the hurdles in technical know-how, regulatory barriers and other issues,” they said in a note. “Shale outside North America may become relevant vis-a-vis global oil and gas supply (and thus prices) beyond 2020, but over the next three to four years it will emphatically not be needle-moving.”

Only China and Argentina now have commercial-scale shale production outside the United States and Canada, according to Raymond James. Since the U.S./Canada surge, Argentina has been the only “clear-cut success encompassing both oil and gas,” while China has shown promise in scaling up its natural gas volumes. Meanwhile, the shale takeover in Poland and Europe in general “has turned out very badly.”

While Mexico and Russia have significant “theoretical” shale potential, it will take time to tell whether development proves worthwhile.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) in 2013reported that Argentina may have the most prospective shale oil and gas outside North America.China was identified by EIA in 2011 as having more shale gas resources than the United States. But other shale-rich regions haven’t fared as well. Outside of the United States and Canada, shale development even in themost favorable spots is still years away.

According to the EIA, combined U.S. and Canadian resource totals 286 billion boe of technically recoverable shale resource, which is 19% of the global total. The “global” total is defined as the 46 countries assessed by EIA, which includes nearly all of the major producers that are not members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), as well as a few OPEC members. In aggregate, China was in first place, with 218 billion boe, followed by the United States (182), Argentina (161), Algeria (124), Russia (122), and Canada and Mexico (tied at 104).

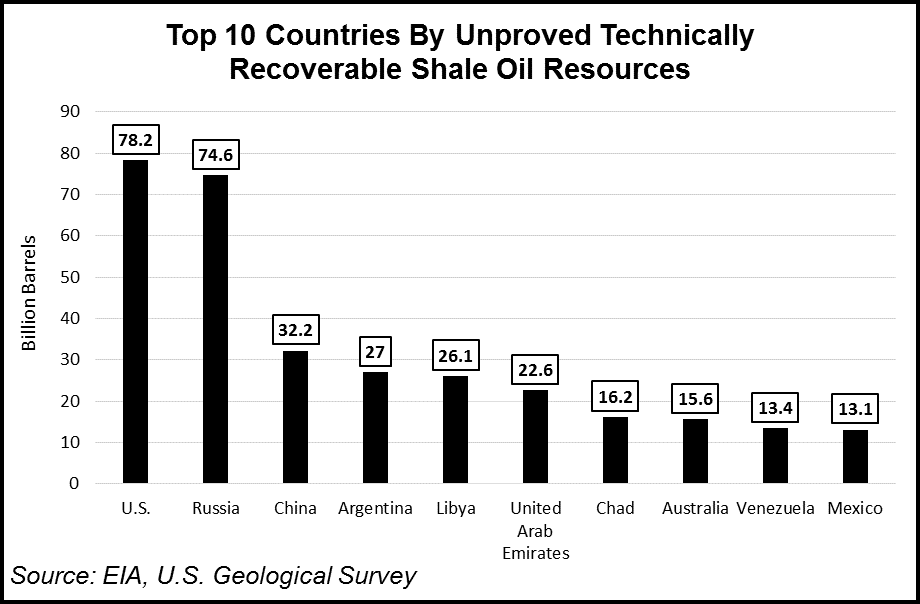

“Zeroing in on shale gas, China is well out in front, followed by Argentina, Algeria and the U.S.,” said Molchanov and Dmirdjian. “When it comes to shale oil, the U.S. is first, with Russia narrowly behind, and China and Argentina further behind.” But countries with substantial shale resource in place are found on every continent, they noted.

China “offers boundless running room,” with strong government support and a drive to reduce carbon emissions. However, the national oil companies have limited expertise and are slow-moving organizations, with water scarcity also an obstacle. Even so, shale gas output in 2016 reached around 1.0 Bcf/d, doubling from 2015 levels, which in turn had tripled from 2014,” Most of the development is underway in the Sichuan Basin, with horizontal well costs estimated at $11-13 million and falling.

“The government’s official target for 2020 is 3 Bcf/d, which we think looks realistic given the visible growth spurt over the past two years,” said the Raymond James analysts. BP plc likely has the most leverage to Chinese shale after signing a second production sharing contract to work in the Sichuan Basin with state-owned PetroChina Co. Ltd. in 2016.

Argentina is developing shale oil along with shale gas, mostly in the Neuquen Basin, which is estimated to hold “about as much shale resource as every other South American country combined,” with similar characteristics as the Eagle Ford Shale, according to Raymond James. Chevron Corp., working with partners, has been a leader in developing the Vaca Muerta formation.

While some countries, like Poland, have, for now, proved to be shale exploration flops, other countries, including Mexico, are too early to judge.

“Foreign investment in conventional onshore and deepwater resources is starting to pick up, but shale has been notably absent,” said analysts. “Northern Mexico’s shale optionality provides an intriguing long-term resource development opportunity, albeit with poor visibility.” The Burro-Picachos Basin near the Texas border, is the southern flank of the Upper Cretaceous Eagle Ford Shale, where as of mid-2016 Petroleos Mexicanos had drilled less than 30 shale wells.

“The fact that production metrics were markedly lower than in the Eagle Ford is probably a function of inadequate stimulation rather than inferior geology, and therefore can be remedied with more operational learnings,” said analysts.

Also of interest down Mexico way is the Upper Jurassic Pimienta formation, “a source rock that correlates with the Cotton Valley-Bossier-Haynesville of East Texas. This formation is found in the Burgos and Tampico-Misantla basins.” An inaugural shale auction had been set for 2015, but citing low commodity prices, the government postponed it, and it’s still unclear when it will be revived.

Russian shale also is too soon to judge. Horizontal drilling in the country is “well established” and accounted for about 25% of drilling footage during 2014-2016, according to Raymond James. “However, production of actual shale is de minimis.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |