Regulatory | E&P | NGI All News Access

OK Quakes Trending Down After State Cuts Wastewater Injections, Research Finds

The number of earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater near oil and gas disposal wells in Oklahoma should continue to decline over the next few years as a result of state regulations reducing wastewater injection volumes, according to new research from Stanford University.

In an article published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, Stanford’s Mark Zoback and Cornelius Langenbruch, professors with the university’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, predicted based on statistical modeling “that widely felt…earthquakes in the affected areas, as well as the probability of potentially damaging larger events, should significantly decrease by the end of 2016 and approach historic levels within a few years.”

Researchers have found a correlation between a recent uptick in seismic activity in Oklahoma and the disposal of salty produced water — a byproduct of oil and gas extraction — in underground injection wells targeting the Arbuckle Formation. Regulators with the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) have taken a number of steps to curtail injection volumes of wastewater in response to the earthquakes.

The OCC recently ordered 50 wastewater injection wells near Cushing to either cease or scale back their operations after a magnitude-5.0 earthquake struck near the crude storage and transportation hub.

In March, the OCC ordered more than 400 injection wells targeting the Arbuckle to cut volumes by 40% below 2014 levels.

Zoback and Langenbruch concluded that, based on data modeling the correlation between injection volumes and induced seismicity in Oklahoma, the OCC’s actions should soon start to have a positive effect in reducing the number of widely felt earthquakes in the state.

“Although the mandated injection rate after May 2016 remains almost twice as high as it was in 2009 when the induced earthquake sequence started, it is now distributed over an area twice as large as it was in 2009,” they wrote. “…The highest earthquake rates to date are observed several months after peak saltwater injection rates have been reached. After February 2016, the earthquake activity markedly decreased, and in May 2016, the combined earthquake rate in [central and western Oklahoma] is as low as in early 2014.”

“Several months after wastewater injection began decreasing in mid-2015, the earthquake rate started to decline,” Langenbruch said of the study’s findings. “There is no question that there is a significantly lower seismicity rate than there was a year ago.”

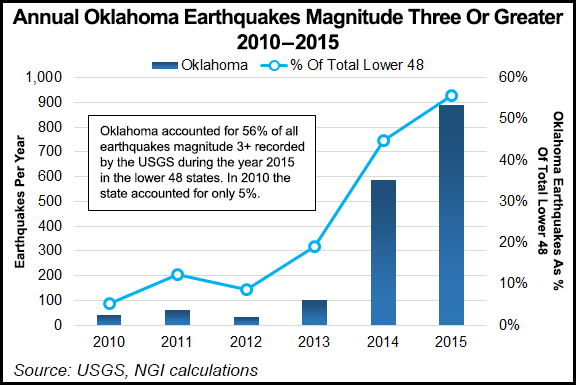

Seismic activity in the state peaked at two or more magnitude 3.0 or higher quakes per day in 2015, according to the research, compared to about one such quake per year prior to the start of the induced seismicity in 2009.

But the risk of a potentially damaging larger earthquake will remain in Oklahoma even as the overall rate of seismicity decreases, the researchers found.

The largest-ever quake recorded in the state measured magnitude 5.6 and occurred near Pawnee in September.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |