NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | LNG | Markets | NGI All News Access

Global NatGas Pricing to Revolve Around U.S. LNG, Henry Hub, Goldman Analyst Says

The rapid growth of liquefied natural gas (LNG) supply coming online over the next few years will lead to a global convergence of natural gas pricing “centered around the U.S. market and Henry Hub,” according to Goldman, Sachs & Co. Senior Commodities Analyst Christian Lelong.

Lelong provided his firm’s outlook on global LNG markets and the emergence of the United States as a major gas exporter as part of a keynote speech at last week’s LDC Gas Forum in Chicago.

Between investments in LNG and pipeline exports to Mexico, the United States is on track to export 9-10% of its total natural gas production by the end of the decade, Lelong said.

“We could almost think about Mexican exports as baseload, going to be a pretty predictable, steady flow, not a lot of risk there, but LNG exports will be a bit more like peak load,” he said, adding that he expects “many years of positive demand growth” in Mexico as more power plants, factories and households convert to using natural gas.

(Lots of eyes will be on Mexico in the coming years. Two years since the formation of Cenagas, Mexico’s natural gas pipeline system operator, Director General David Madero sat down with political scientist and NGI correspondent Dwight Dyer to talk about what’s ahead for infrastructure as the country’s natural gas market evolution unfolds. The result is an exclusive three-part NGI special report that begins on Wednesday in Daily GPI.)

LNG will likely be “somewhat intermittent,” Lelong added. “If the price arbitrage to Europe is open, they should be running flat out, but if Europe has a mild winter, or if Gazprom cuts their prices and the LNG market is a little bit slow to respond, you may see that [opportunity] closing for a period of time, and that means that LNG exports could drop from 100% utilization to 50% or 35% utilization.”

“Over time, these swings in demand from these LNG facilities will be noticeable, and how that affects Henry Hub, how that affects demand for storage, how that affects regional price points in the U.S. I think is going to be an interesting dynamic to watch…We think we’re headed towards that kind of market probably two years from now.”

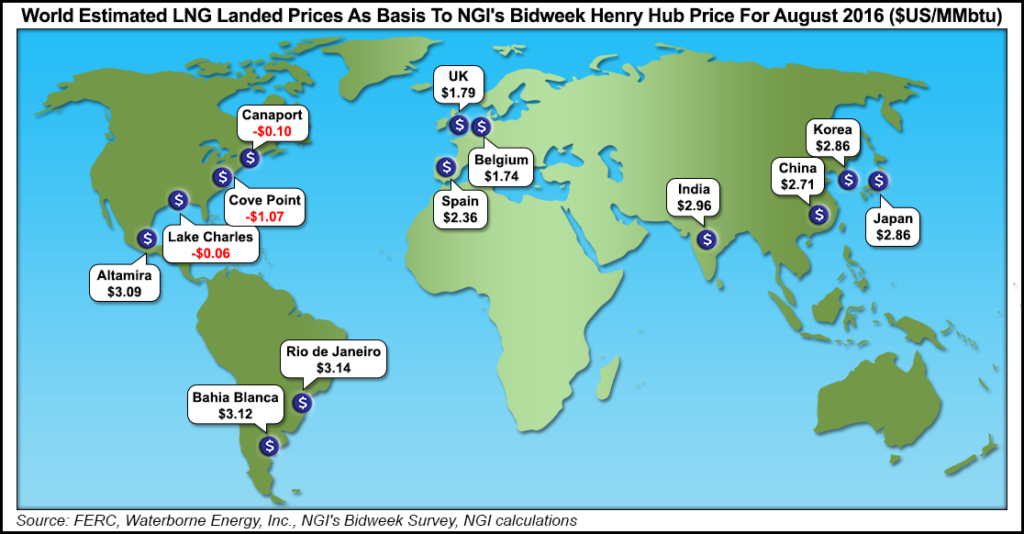

Variability in the actual LNG export volumes will likely turn the United States into a global natural gas swing producer and make U.S. pricing around Henry Hub more important as a benchmark for LNG prices around the world, according to Lelong. He pointed to the shrinking differential between Henry Hub and global LNG prices over the last few years.

“We think this is a trend that will continue, and given the size of the U.S. market, being the biggest in the world, and given the role of the U.S. as a swing exporter, unlike pretty much every other exporter, we think that will continue to drive this convergence towards Henry Hub, and the convergence is having an impact. It’s having an impact on demand,” Lelong said.

“…As Europe gets cheaper gas, markets like the UK [United Kingdom] start to see the same coal-to-gas switching story we’ve seen in the U.S. in the last five years. It’s now happening in the UK, and now gas is well ahead of coal in the fuel mix, all because of access to cheaper gas.”

The UK is an interesting example, Lelong said, pointing to the deregulation of its gas market. “Same story happened here 30 years ago. It’s happened in the UK, and we think it’s going to happen in other markets as well. It’s the beginning of global gas becoming a normal commodity that doesn’t price off the fundamentals of oil.”

In 1H2017, Lelong said he expects “a partial reversal of coal-to-gas switching” as Henry Hub prices rally to around $3.15/MMBtu in the first quarter and $3.30/MMBtu in the second quarter. “That’s the type of price that we think is necessary to bring more rigs into legacy shale plays like the Haynesville. And with a higher gas price, we would expect to see a response in the power sector.”

But this move back to coal is likely to be short-lived, he said. The volume of new LNG supply entering the market after exporters “overbuilt” the last few years will create a global gas glut. “The way we think this gets balanced is by low prices and substitution for coal with gas.”

Describing the expansion of U.S. LNG export capacity over the last few years as “staggering,” Lelong said that “the bottom line is the U.S. is adding enough capacity to fully satisfy European LNG demand, even accounting for Europe doubling its ability to import LNG as prices drop. So it’s a big shock in terms of new LNG supply, and we do see Europe as being one of the key markets.”

In the medium- to long-term Henry Hub will likely settle in around $3/MMBtu, driving “European gas prices at $4/MMBtu give or take a few cents. We think at that level you do start to get a decent amount of coal-to-gas switching. Regulators can also try to reinforce this trend, potentially by raising carbon prices.” Geopolitical dynamics could also factor in, as Russian gas competes with LNG in Europe, Lelong said.

Meanwhile, China, looking to curb coal pollution, is also increasing its investments in gas infrastructure. And the ability to lease floating storage and regasification units has opened up LNG to a number of other countries with “very seasonal demand,” such as Brazil and Argentina, Lelong said.

But while global gas demand is “good” at the moment, it’s far from the kind of market many LNG exporters envisioned when they invested in building their capacity, he said.

“In global gas, we see a lot of people are counting on the early 2020s” for a price response in the $7-10/MMBtu range to stimulate new infrastructure investment, Lelong said. “We think that’s maybe a little too much. We think this glut is probably going to last until the late 2020s instead, because not only is energy demand growing a little bit more slowly than before, you also have competition…other markets outside the U.S. are also getting into renewable energy…and there’s also the fact that a lot of this demand that I’ve been describing is price sensitive.

“You cannot expect European imports and Chinese imports and Pakistani imports to stay flat if you want gas prices to go from $4/MMBtu back to $8/MMBtu. So we think most likely for the next 10 years we’re going to have global gas prices that are in line with” production and export costs without increasing “all the way to inducement pricing. But that time will come.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |