E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Macquarie Strategist Sees Volatile Natural Gas Prices, With $1.50-$6.50/MMBtu Range Possible

Low oil prices could bolster a dry gas strategy, keeping liquids prices low and cutting into associated gas production, just as a raft of new petrochemical, methanol and other manufacturing projects that would increase gas demand are nearing operation.

Given the number of factors playing on the natural gas market, volatility is a given over the next several years. But, “probably the most important thing as far as gas prices go, is oil,” said Vikas Dwivedi, global oil and gas strategist for the Sydney, Australia-based Macquarie Group, pointing to a bullish slant for gas if oil prices stay low. Dwivedi shared his insight in a keynote address during the 16th Annual LDC Gas Forum Southeast in Atlanta on Tuesday.

“Because if oil prices don’t rally, let’s say we get stuck in the $40-$50/bbl range, and there’s a lot of people that view it that way. We don’t. It’s not a crazy outcome if oil stays low. What happens right? Associated gas production doesn’t go up. Wet gas that’s driven by [natural gas liquids] economics suffers…Altogether, the higher oil prices go, the more bearish it is for gas.”

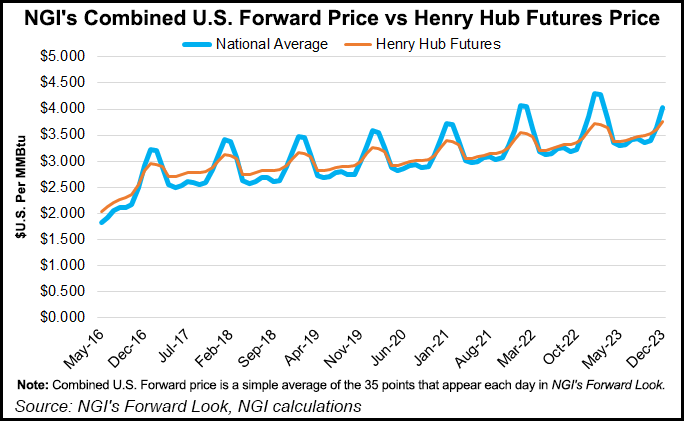

Of all the commodities Macquarie studies, gas is expected to be “the highest volatility commodity or security. The range is massive: $1.50-$6.50/MMBtu,” Dwivedi said, with weather a big input. But the infrastructure issues are going to be more pronounced as well.

To get to a price of $6/MMBtu, he said it would likely take a combination of “weather, infrastructure constraints and low oil prices. All of which as single items, are very possible. Could you get all three at once? Absolutely.”

He added, “If oil stays below $50/bbl for the next three years, you’re going to have legitimate scenarios of going back to $6/MMBtu, and I know, sitting here at $1.95, it seems impossible, but that’s exactly what makes it such a volatile market.”

Over the last five years, U.S. crude oil production has increased by about 5 million b/d, resulting in about 12-13 Bcf/d of associated gas, he said.

“It’s hard for any industry to overcome when you’re getting that much effectively free supply,” Dwivedi said.

While associated gas production from oil wells isn’t falling as fast as the bulls would like, it has stopped growing, suggesting the gas price outlook is “not all dire despite the fact that we’ve been below $2/MMBtu for a while.”

Gas production, in large part driven by the “monster” Marcellus and Utica shales, has “still been resilient. It is starting to plateau and then fade a little bit. We could still see it staying in the 71 Bcf/d range, maybe going below 70 Bcf/d. That’s still very positive for prices, because previously, in the past several years, we’ve had gas production grow 5-6 Bcf/d…while prices were falling,” Dwivedi said.

“Effectively, gas production became an independent variable. It didn’t care about much at all. It was just going to grow. And that’s a great recipe to have low prices. We may finally be seeing a little bit of a slowdown in that.”

Meanwhile, demand growth is “accelerating” on pipeline exports to Mexico, liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports overseas and for industrial facilities.

“When you start adding it up…ammonia, methanol, petrochemicals, steam cracking…primary metals manufacturing, there’s a lot of good stuff linked to cheap gas,” Dwivedi said. “If you look back over the last several years…[we] just really haven’t had that much real industrial demand growth, because these things take a long time. They’re close right now, sort of at the doorstep.”

In the last seven to eight years of unconventional production growth, “the only demand growth we’ve had is from coal-to-gas switching and some power plant retirements. Significant demand growth from industrial and things like LNG are just now coming. It’s important to keep that in mind.”

When thinking about volatility, it’s also important to keep in mind the 1 Tcf of demand destroyed by an outlier winter in terms of temperatures, said Macquarie’s strategist.

“That says a lot about next winter. If we just get back to normal degree days, you’ve got a lot of built in demand growth. We think that it is pretty easy to forget about right now. We were so full of storage when we entered March,” he said. The demand destroyed during winter 2015/2016 roughly matches the additional demand created during the extreme cold of 2013/2014.

“But if you think about it, a mild winter should never destroy as much demand as a really cold winter should generate, and that tells you really how mild this [winter] was. It actually stretches that question of ”how mild can mild get?’ If you think about it in standard deviations, this last winter was over three standard deviations milder than normal, and the polar vortex was only two standard deviations colder than normal, so this was a freakishly warm winter.”

Adjusting demand for average temperatures next winter, the result “could catch the market napping and surprise to the upside” in terms of gas prices.

Dwivedi posed a hypothetical.

“What happens when you’ve got a lot of inventory and the day-to-day cash market is tight? Do you get a rally, or is the high inventory the bigger driver? Or vice versa? What if it’s [like it was] after the polar vortex winter? We ended with 830 Bcf, which was the lowest ever adjusted for the size of the market, and then the day-to-day got really soft. We were oversupplied, production grew 6 Bcf/d that year following the winter. Even with very low inventory, prices fell really hard.

“We think there’s a lot of risk here that there’s a lot of comfort and even complacency to finish March at such a high inventory level, but if these demand numbers prove right and supply doesn’t grow, then the day-to-day could be a lot tighter than people think. This massive amount of inventory may not do a lot to keep prices from surging.”

Another factor that could contribute to volatility is the lack of growth in storage because of poor economics for such projects, Dwivedi said. The market could have 20-25 Bcf/d of additional demand in five years while operating with the same storage capacity it had three years ago.

There’s also the uncertainty about whether enough takeaway capacity is available to move production to market, as projects face regulatory delays and as liquidity stress among exploration and production companies creates additional risk for pipeline operators needing firm commitments to move forward (see Daily GPI, March 9; March 8; Feb. 23).

“The effective tearing up of capacity contracts, firm commitment contracts, that’s going to put a little chill on new investment,” Dwivedi said. “If you can’t count on your anchor tenant as your pipe developer to be there, you have to be a lot more careful in investing.”

While production growth in the Marcellus and Utica has “been [like] clockwork” in corresponding with new takeaway capacity, “now it’s changing a little bit. We’re seeing a lot more delays, and things are a little riskier in terms of what’s going to come on.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |