Utica Shale | E&P | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Some Utica Operators Revert to Wider Well Spacing to Cut Costs; Others Testing Limits

In an effort to save money wherever possible, some operators in the Appalachian Basin are reverting back to wider interlateral well spacing, choosing, for now, to lose drilling locations and gain back capital as they search for more ways to weather the commodities downturn.

It’s too early to say definitively whether the moves by Gulfport Energy Corp. and Rice Energy Inc. to shift from 750-foot spacing back to 1,000-foot spacing in the Utica Shale are the makings of a trend. But at the least, the decisions have revived a debate about reservoir management and optimal drainage in the Northeast amid a challenging price environment.

Only in recent years have operators focused sharply on squeezing more wells onto their shale acreage, boosting reserves, returns and in some cases production. They set out to more effectively drain their reservoirs without the old problem of interference. After mixed pilot tests, some companies began developing their acreage on tighter spacing.

Producers in Appalachia and across the country have turned to oilfield services, labor, production strategies and reviewed each line-item on their balance sheets to drive down costs, spacing is yet another tool, among many, that they have in their box to save capital.

Gulfport and Rice’s step back toward wider spacing comes as more operators are retreating exclusively to their dry natural gas acreage, where low breakeven prices and prolific wells are being used to defend against the downturn (see Shale Daily, April 7). A debate over spacing has also been revived by nascent development in the deep, dry Utica of Pennsylvania and West Virginia, where operators are still learning how best to develop the horizon.

In February, Gulfport said it would shift its development program back to 1,000-foot interlateral spacing in the dry Utica from the 750-foot spacing it started employing across much of its Ohio acreage last year (see Shale Daily, Feb. 18). It plans to keep running 600-foot spacing in its Utica condensate windows, but it has highlighted a strategy for this year that finds it focusing almost entirely on dry gas production. Wider spacing, CEO Michael Moore said, would increase the company’s acreage held-by-production and minimize leasehold costs, saving about $30 million this year on land renewals.

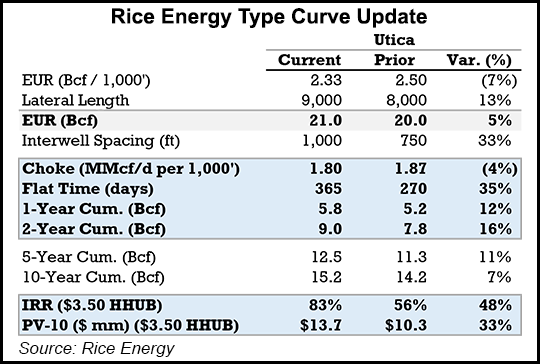

Days later, Rice Energy announced a similar move in the Utica, but for different reasons. The company said it had observed interference between wells spaced at 750-feet (see Shale Daily, Feb. 25). The Utica wells, management said, were also showing steeper decline curves than expected, but they added that longer laterals would make up for wider spacing and actually boost absolute Estimated Ultimate Recoveries (EUR) in the Utica from 20 to 21 Bcf. Rice’s decision, however, was partly underscored by lower commodity prices, as well.

“The widened Utica spacing is a function of two primary factors: lower gas prices and increased well productivity,” said CEO Daniel J. Rice. “From a returns and present value perspective, in this commodity price environment, well economics make more sense at spacing wider than 750 feet in order to maximize PV-10 field-wide.”

The moves highlight the variety of completion methods in the play, too. Gulfport made a purely economic decision. It puts less energy into completing its wells. Rice typically completes with more frack stages, tighter frack clusters and more proppant. In any event, Topeka Capital Markets analyst Gabriele Sorbara said wider spacing for both companies is a prudent move in the current environment.

“You know it probably is going to be a trend. You’re seeing that not just across the Utica, but across all these plays in the United States, the companies are electing to not have tighter spacing, or back-off tighter spacing, because commodity prices are lower,” Sorbara said. “Naturally, you would go tighter — and you do want [well communication] at the end of the day — 10-15% communication is fine as long as you have higher commodity prices and you can make up the erosion in EUR with higher commodity prices.

“You’re going to lose locations [with wider spacing] at Gulfport, you’re going to lose locations with Rice. But I think it’s temporary. Two or three years down the road, as commodity prices improve, companies could revert back to tighter spacing.”

The shale era has been defined by efficiency. Spacing identifies the location and number of wells that can be drilled to drain a reservoir. With wider spacing, fewer wells can be drilled on a unit. With tighter spacing, more wells can be drilled on a unit. The technique affects land costs and returns.

“What you’re really trying to do is optimally develop the resource. So you’re trying to balance your investment with the production you get in return for it,” said Consol Energy Inc.’s Craig Neal, vice president of gas operations. “I think almost always that you get more reserves per square mile by drilling tighter, but there’s a point of diminishing returns.

“That’s what we’re all trying to do, is come up with that optimum spacing, and that can certainly change with product pricing. Once your product becomes over-valuable, it may be worse trying to go in there and drill a little more closely to optimize shareholder return. The interlateral spacing won’t necessarily stay the same if there are significant swings in product pricing.”

The Utica has evolved over the last year or two, with operators striking out to develop the formation in Southwest Pennsylvania and West Virginia (see Shale Daily, Aug. 25, 2015; March 26, 2014). Consol, Range Resources Corp. and EQT Corp. have all tested Utica wells between 59-72.9 MMcf/d (see Shale Daily, July 29, 2015; July 23, 2015; Dec. 15, 2014) in Pennsylvania. Those wells are deeper, with higher pressures that require different equipment. Each operator is focused on driving well costs down and figuring how best to drill and complete the formation.

Neal said Consol is “very pleased” with its Gaut 4IH deep Utica well in Westmoreland County, PA, which tested last year at more than 61 MMcf/d, saying “we still have some high quality Marcellus assets that will compete, but we see these [Utica wells] to be equal or in many cases better.”

Neal said the Gaut utilized a modified isochronal test — a multi-rate flow test designed to gauge well deliverability — that was partly used to help determine optimal spacing. The Switz pad in Monroe County, OH, has three wells spaced at 1,100 feet that is also helping Consol learn more about spacing in the play.

“If that allows us to save on land costs, that will be fine, but we’re really going to be driven by the proper development of the resource,” Neal said of the 1,100-foot spacing on the Switz pad. “Those two well pads right there are going to be very important to determine the appropriate interlateral spacing in each of those areas. The extended testing that we’re doing on Gaut is really going to allow us to do that on one well. We’re doing some modeling on that and coming to conclusions so when we go to a development mode there, we’ll drill those at the appropriate spacing without having to try and learn it by seeing interference ourselves.”

Since 2014, Eclipse Resources Corp., Gulfport, Rex Energy Corp. and Antero Resources Corp. have all announced tighter spacing (see Shale Daily, June 3, 2015; Feb. 27, 2015; Sept. 16, 2014). Other operators, such as EQT Corp., hinted at how spacing is regularly in flux. For some, wider spacing might not be an issue this year when it comes to saving on land costs.

“Most of our leases contain shallow wells, which continue to produce,” EQT spokeswoman Linda Robertson said. “That production holds our lease until production ceases. We are drilling at whatever spacing we have determined is the most economical in each area.”

When asked in February by JPMorgan Chase analyst Arun Jayaram to discuss the debate “that’s kind of been brewing in earnings season regarding the appropriate well spacing in the Utica to get the optimal drainage,” Antero CEO Paul Rady said the company is continuing to assess its spacing in some areas.

While Antero runs 750-foot spacing on most of its acreage, the company’s drilling inventory is based on 1,000-foot spacing. Most of the company’s drilling, however, has taken place on its wet gas acreage and it has yet to determine what the best range is for dry gas in Ohio.

“We certainly run our economics and our returns, and 750-foot works well for us,” Rady said. “And there are trade-offs, but that’s what we see as the best answer at this point. We haven’t gone as far down-dip in Ohio as many of the other operators, so whether 750 or 1,000 is appropriate as you go farther east — not sure — we’ll have to judge for ourselves.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |