Shale Daily | E&P | NGI All News Access

Data Indicates Fewer Small Earthquakes in Oklahoma in Second Half of 2015

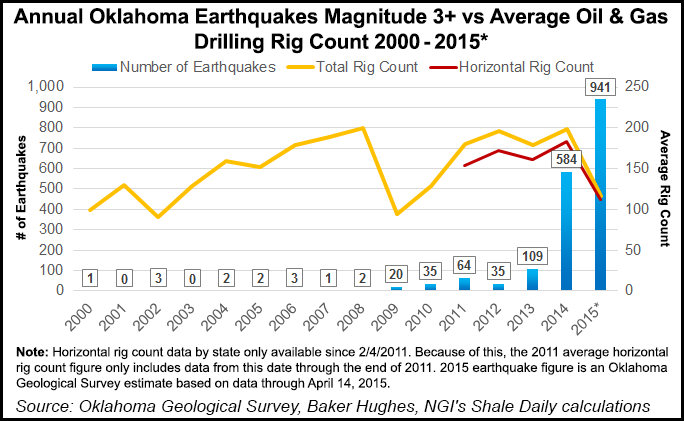

Actions taken by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) to mitigate earthquakes, coupled with a possible decline in the state’s oil and gas production for 2015, may have contributed to a slight decline in the number of small temblors to hit Oklahoma during the second half of the year, according to the Oklahoma Geological Survey (OGS).

Meanwhile, the OCC’s Oil and Gas Conservation Division (OGCD) issued a new directive Monday in response to a series of earthquakes that hit the state around the holidays, including a 4.3-magnitude temblor that struck near Edmond last week (see Shale Daily, Dec. 29, 2015).

OGS Director Jeremy Boak told NGI’s Shale Daily that the state hasn’t seen a decline in the number of large earthquakes — measuring 4.0 on the Richter scale or higher — but the number of temblors measuring 3.0 magnitude or greater appears to have declined, from about 480 in the first half of 2015, to around 400-420 during the second half.

Boak said the agency’s staff had yet to compile data on earthquakes that struck the state around the holiday season, but if the 400-420 figure holds true it would be the first six-month period since 2012 that there has been a reduction in the number of earthquakes.

“It’s just a slight decrease,” Boak said Monday. “It’s not enough to make a difference in terms of satisfying anybody that we’re past the [danger], but it may be indicating that there’s some effect from the actions of the OCC, and the effect of the [commodity] price drop on total production.”

For the past several months, the OGCD has been taking action to reduce the number and intensity of earthquakes in the state, ordering some disposal wells to shut down operations and others to reduce the volume of wastewater they accept. The watershed moment came in April, when the OGCD issued new rules for injection well operators working in “areas of interest” that inject into the Arbuckle Formation (see Shale Daily, April 2, 2015).

“It’s a pretty small reduction — not enough to solve the problem, but it’s at least saying something is going on that might suggest the OCC is being effective in what it’s doing,” Boak said. “There’s always a possibility that it’s a lull. Earthquakes are very sporadic.”

According to Boak, earthquakes from injection wells in Oklahoma are not being triggered by water used to perform hydraulic fracturing (fracking), which is mostly freshwater. Rather, they are being triggered by extremely salty water that is a byproduct of oil and gas production. Oil and gas drilling in Oklahoma also targets limestone formations — like the Mississippian Lime and the Hunton Formation — which contain more water.

“The water that we’re producing from these formations is ancient seawater that’s been interacting for tens of millions of years with the rock around it, and in many cases it’s as saline — or more saline — than the Dead Sea or the Great Salt Lake,” Boak said. “This formation water has been down there in rocks that were busy generating oil and gas, and so there may well be organic compounds dissolved in it.”

Boak also cited a June 2015 report by Stanford University researchers F. Rall Walsh III and Mark Zoback, which showed increases in seismicity in Oklahoma followed five- to 10-fold increases in the rates of saltwater disposal (see Shale Daily, June 19, 2015).

Oklahoma’s injection well operators are disposing the ancient seawater “in a horizon that sits right down on the basement, because it was as far as you could get from groundwater,” Boak said. “It’s a very permeable formation, slightly under-pressured. You could basically pour it down the well, more or less; you didn’t need to inject it under any pressure. It was quite happy to take your water.

“It appears that part of the reason [the earthquakes are occurring] is that it was spreading it around into, and connecting to a network of fractures that lead deeper into the basement, and there’s pressure communication along that pathway down to deep faults.”

That, in turn, has created something resembling a lake in the Arbuckle Formation, the last formation before the crystalline basement, Boak said. “It’s applying just enough water pressure underneath through this connection pathway, where these faults that are relatively close to their critical stress,” he said. “You’re adding a little bit of water pressure in that fault, and that is reducing the stress that’s holding it closed.”

Boak said the average depth of the earthquakes being felt in Oklahoma is five kilometers, well below the sedimentary rock from which oil and gas is produced.

New Directive by OGCD

On Monday, the OGCD ordered Pedestal Oil Co. Inc. to enact a 50% reduction in intake volume at its C.J. Judy 1 injection well. The division set a deadline of Jan. 18 for Pedestal to complete the first 25% reduction, followed by a Feb. 1 deadline for the remaining 25%. The Judy well is located about 3.5 miles from the epicenter of the earthquake near Edmond, which struck at 5:39 a.m. CST on Dec. 29, 2015.

The OGCD also ordered operators of four more injection wells, all located within 10 miles of the Edmond quake, to reduce intake volumes by 25%, again by Jan. 18 (13%) and Feb. 1 (12%). The wells — Harvey 1-11 SWD, McGrew 1-A, Wishon SWD 1-25 SWD and Dahl SWD Facility 1 — are operated by Devon Energy Production Co. LP, Grayhorse Operating Inc., New Dominion LLC and Taylor RC Operating Co. LLC, respectively.

Operators of 11 disposal wells within 15 miles of the Edmond quake were also ordered to conduct reservoir pressure testing.

“We are working with researchers on the entire area of the state involved in the latest seismic activity to plot out where we should go from here,” said OGCD Director Tim Baker. “We are looking not only at the Edmond area, but the surrounding area as well, including the new seismic activity that has occurred in the Stillwater area.”

The OGCD added that Pedestal and Devon “have agreed to suspend operations” at their Judy and Harvey injection wells to “aid in the research effort.”

Few Alternatives

Although Gov. Mary Fallin created a fact-finding work group in late November to find ways for produced water to be recycled or reused, rather than injecting it into underground disposal wells (see Shale Daily, Dec. 2, 2015), Boak said there were few alternatives, which in turn leads to questions about the viability of plays like the Mississippian Lime.

“One option is to inject into different horizons that are less well-connected to the basement, but I have a feeling there will be a lot of wariness of that approach,” Boak said. “Some of the faults go through, and you might find some that are still managing to communicate. You would have to have strong confidence that you really have a good barrier to prevent this water from communicating downward.

“This is already being used in a few cases; instead of going for a permit in the Arbuckle — which was the easiest and the most friendly for taking water — the operators are coming up to different horizons and using those for injection.”

But Boak said operators will never be able to get away from the ancient seawater entirely.

“It’s a sludge that going to be relatively unpleasant to dispose of. You can probably reuse some of that water, but it’s an interesting question, in a time when [commodity] prices are so low. Is this play going to remain viable simply because of the need to dispose of the water?

“The Mississippian Lime has always been a tough sell simply because it produced so much water; it may just have become a lot tougher.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |