NGI Archives | NGI All News Access

NatGas Fracking Assessment to Shape Michigan Policy

A three-year comprehensive assessment of hydraulic fracturing at natural gas wells, completed by the University of Michigan (U-M) on Wednesday, is designed to give policymakers more insight to shape future drilling rules.

The two-part, 200-page integrated assessment focuses on high-volume hydraulic fracturing (HVHF), a fracturing (fracking) practice that today is limited but should see growth in the coming years. HVHF is defined by the state as activity that is intended to use more than 100,000 gallons of fracturing fluid.

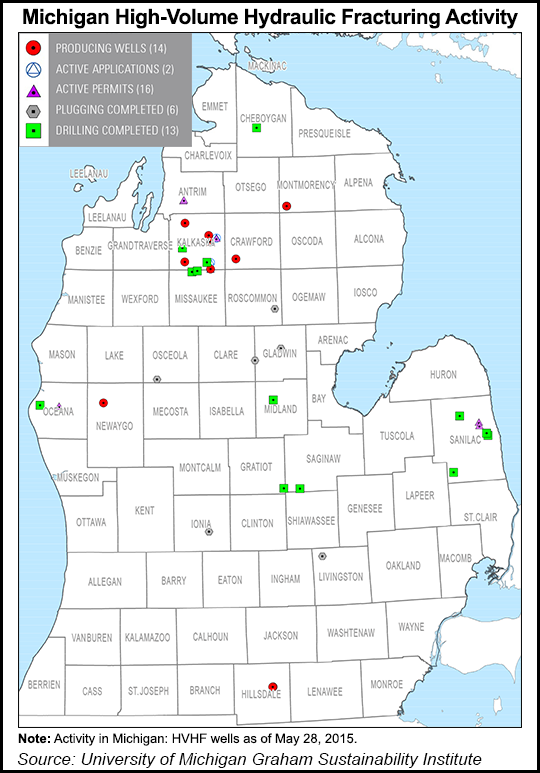

Only 14 such wells currently produce natural gas in Michigan, but the authors took into account the possibility that HVHF could become more widespread as gas prices rise, which in turn would create jobs and boost economic growth.

The first phase of the project, published two years ago, featured seven detailed, peer-reviewed technical reports (see Shale Daily, Sept. 9, 2013). Gov. Rick Snyder had said the preliminary findings already helped to craft changes to state natural gas and oil drilling rules.

“As a key decision maker on this topic, it’s been important to have state engagement throughout our process, and it’s great to know that the work has already been useful,” said U-M’s John Callewaert, integrated assessment director of the Graham Sustainability Institute, which oversaw the project.

Prospective gas resources in the state include the Antrim Shale and a portion of the Utica Shale, which extends into the Collingwood formation, a shale/limestone chalk on the Lower Peninsula. The formation has attracted Encana Corp., Chesapeake Energy Corp. and Chevron Corp., among others (seeDaily GPI, Nov. 10, 2010; May 20, 2010).

The key contribution of the final report is an analysis of Michigan-specific options in the areas of public participation, water resources and chemical use related to fracking.

“This report does not advocate for recommended courses of action,” Callewaert said. “Rather, it presents information about the likely strengths, weaknesses and outcomes of various courses of action to support informed decisionmaking.”

The state previously treated fracturing as another development activity, but “the public has had few opportunities to weigh in on whether and where” it occurs, the authors noted. The report suggests giving stakeholders more notice on places targeted for drilling leases. It also suggests allowing those people affected by permitting new wells to seek public hearings.

In response to more than 150 public comments and feedback from an expert review panel and advisory committee, the authors made hundreds of revisions to improve and clarify content. For instance, HVHF revisions finalized earlier this year by the state’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) were incorporated (see Shale Daily, Oct. 23, 2013).

The state now requires more preparatory work and water level monitoring of HVHF projects. In addition, notifications are required at least 48 hours before such operations begin. The pressures/volumes used have to be reported, and well operators are required to post information about their use of chemical additives to the online FracFocus Chemical Disclosure Registry.

U-M’s report has “helped us see an opportunity to strengthen our protection of water and give the public more information,” Snyder said.

Grenetta Thomassey, who directs the Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, was a member of the project’s advisory committee. She said the U-M team took care with every phase of the project. “We hope that decisionmakers find the final document useful and important enough to take additional actions to improve oversight of fracking activities in our state.”

The report, which cost roughly $600,000, was funded by U-M and written by faculty researchers with support from students and Graham Sustainability Institute staff.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |