Haynesville Shale | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

U.S. E&Ps Using Slowdown to Build Better Onshore Oil, NatGas Wells

Anadarko Petroleum Corp. plans to drill 70 wells in Colorado this year versus 35 in 2014 using only one rig. Comstock Resources Inc. upended completion designs in the Haynesville Shale and is flowing more natural gas than ever. The names change but the story hasn’t — producers are lifting more oil and gas out of the ground and better costs than ever before, and it’s going to be repeatable year after year, according to a new analysis.

Listen to any recent second quarter conference call by any exploration and production (E&P) company and it’s clear that most are expecting low commodity prices to continue. Keep listening and another theme is constant. More production is flowing at much lower costs.

Wood Mackenzie’s Robert Clarke, research director of global unconventional oil and gas, said the better results have become the norm, borne out in the data.

“I think producers are extremely committed to maintaining as much margin on their projects as they can as revenue has dropped as quickly as it has,” he told NGI’s Shale Daily. E&Ps have “two options to help manage that. One is to reduce their costs. And the other is to increase their capital efficiency.”

Expected ultimate recoveries (EUR) have grown by more than 10% a year through better drilling technology, robust basin modeling and experienced asset teams, he said. Those higher EURs are coming despite the sharp decline in the U.S. rig count from 2014 levels. Researchers wanted to test the idea that a less aggressive pace of activity, combined with a sharper operator focus, could improve future EURs even more.

They already had a good test case. When BP plc’s Macondo well blew out in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico five years ago, federal regulators imposed a drilling moratorium that lasted about six months. The players had to sit on their hands before they could begin drilling again, so they stopped running on a “leasing treadmill” and worked on basin science. Once exploration and development ramped back up, the post-Macondo discovery data was better than before the explosion. Average discovery sizes in the GOM after the moratorium grew by 30%, even as the discovery count fell by about half.

Producers were able to capitalize on the slow pace, leveraging the downtime to vet prospects and design better wells, according to Wood Mackenzie.

The slowdown in the onshore today is market-driven and not regulatory based, but the post-price slowdown improvements appear to be tracking the post-Macondo findings — better science makes better wells.

Wood Mackenzie’s researchers used the firm’s proprietary North American Well Analysis Tool to review data in the Fort Berthold formation of North Dakota’s Bakken Shale and sub-plays within the Eagle Ford Shale in Texas. EURs were reviewed for newer onshore wells in each play before and after the 2014 oil price collapse was noticeable. They found that in the Eagle Ford, initial production (IP) rates for newer wells drilled after July 2014 declined. However, the EURs jumped as more focus was put on better reservoir management. EURs across both regions rose after the oil price collapse by around 25%.

“What we’re seeing is that the producers are doing a fantastic job of using technology” to reduce costs and improve capital efficiencies, Clarke said. Wells are being drilled faster, drilling and completion/fracturing (fracking) times are lower and less costly, and E&Ps have improved their understanding of the formations.

“They’re saving costs doing detailed wells, microseismic work and effective frack jobs so they can be more targeted with where they perforate the well and how much sand they use,” Clarke said. “Fundamentally, they’re using a lot of data collection techniques, a lot of heavy, heavy data analytics to understand how to design better wells.”

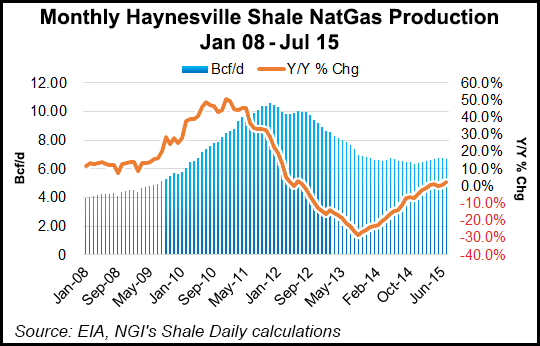

Onshore operator Comstock’s work in the Haynesville is a good example. The huge play has seen its output fall as E&Ps abandoned it for Appalachia. But producers are returning, and they are using basin science to improve IP rates by refracking older wells and drilling better, lower-cost horizontals, said COO Mack Good.

“We significantly changed the previous completion design strategy that we and everybody else had commonly used in the past on the shorter lateral length Haynesville wells,” Good said. “We did this so we could better place more profit per foot at lateral length, better stimulate the reservoir and improve gas recovery rates and EURs.” Results from the first two wells drilled early this year “confirmed that we were on to something.” The result: five horizontals drilled using the new design each delivered 20 MMcf/d-plus in IPs.

“Our current total drilling and completion costs for our extended lateral Haynesville wells is around $10 million, and we believe that we are going to be able to lower this to $9.5 million in the very near future,” Good said.

Anadarko earlier this year had estimated it would take a capital expenditure (capex) plan of around $3 billion to keep production levels flat this year. During 2Q2015, that figure fell to around $2.7 billion, and management sees room for more gains (see Shale Daily, July 29). Apache Corp. has raised its guidance for North American production but it’s cutting its capex (see Shale Daily, Aug. 6). Chesapeake Energy Corp. voluntarily curtailed output in the Northeast during 2Q2015, but production still jumped 13% year/year — and its 2015 guidance is higher (see Shale Daily, Aug. 5).

“What’s unique about this cycle is how service intensity has evolved since 2013,” said Halliburton Co. President Jeff Miller during the quarterly call last month (see Shale Daily, July 20). “Over the last two years, average job size has essentially doubled. And at the same time, both average pump rates and pressures are also up.”

Producers may not be drilling as many wells as they were at the start of 2014, but “they have a lot more capacity do detailed basin science,” said Clarke. “The data matches perfectly with all the comments the companies are making during earnings calls. The message is, ‘we’re going a little bit slower but we’ve got time to think more.’ The metrics are showing that.”

The once average wells “are just getting better and better and better.” At the same time, E&Ps are managing their costs and vendor relationships.

“They’re coming at it from both angles,” Clarke said. E&Ps are spending less to drill/complete the wells, less to manage the entire project, “but getting larger volumes for that…despite companies spending a lot less. The price of oil is down, and earnings are down, but you get this consistent messaging on the earnings calls. ‘Production is up X%,’ and it’s 5%, 10% and becoming better and better.”

No company has money to burn these days, neither the majors or the independents, Clarke said. What’s setting some E&Ps apart are the ones using “predictive analytics, companies that are heavily embedded with big data projects. They should see more in all of the information that they’re gathering. They have shown that it’s better to move slower.”

The “super quick operators used to using a ‘pump and pray’ mentality’ may not have that culture of very experienced technical teams that are looking at the situation and saying, ‘we better move slower, let’s not under invest in technology, let’s not under-invest in all of our internal systems. Let’s really, really view this as an opportunity…” The ones with the “technology culture” are likely to do well.

Wood Mackenzie’s research points to the overall savings taking shape over a few years, with the slowdown in the oilfields resulting in a more positive long-term outlook for the tight shale plays. In that time frame, there could be a “step change in EURs,” along with a steadily improving price environment, which could allow tight oil metrics to surprise on the upside.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |