No Immunity in Appalachia; Oil and Gas Jobs Falling Off

While steep job cuts in the oilfields of Texas and North Dakota have been hard to miss in recent months, the Appalachian Basin has not escaped the trend, with the region’s workforce being trimmed and a less visible retrenchment still evident.

Pennsylvania, where operators in the Marcellus Shale produced a record 4.4 Tcf of natural gas last year, could be seen as a bellwether for how the basin is faring amid the fall in oil and gas prices (see Shale Daily, Feb. 17). But in a region that has become accustom to stubbornly low natural gas prices, prolific production and low finding and development costs, the downturn’s effects have been harder to gauge, especially after discrepancies in the state’s employment data emerged this month.

“There is some noise in the company-reported G&A data with severance and other one-time items,” Topeka Capital Markets financial analyst Gabriele Sorbara told NGI’s Shale Daily, referring to companies’ general and administrative expenses, which include labor costs. “Some operators in Appalachia are not pure-plays. Some have closed offices in different parts of the country, then there are the earlier stage companies that are ramping activity.

“Also, large well positioned companies like Cabot Oil and Gas Corp. are maintaining more activity than peers in the region, as they don’t want to lose their organizational momentum,” he added. “It’s going to be tricky to say how many jobs have been cut in the region. Although with rigs in the region down roughly 37% from the peaks last year, G&A should witness a nice drop in the coming quarters.”

A ”Firestorm’

Complicating matters was a decision made jointly by the Pennsylvania Department of Labor & Industry and Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s administration earlier this month to change the way the state tracks employment in its Marcellus Shale industry. Practically overnight, a seismic shift seemed to appear in the jobs data, going from more than 200,000 jobs in core and ancillary industries to just 89,314 in 3Q2014.

“The administration worked with Labor & Industry to develop methodology that presents a more realistic look at Marcellus Shale numbers in Pennsylvania,” said state labor department spokeswoman Sara Goulet. “This decision was in response to inaccurate reporting of the numbers in the past that told an incomplete story on the shale industry.”

The move rankled industry representatives in what they said was the latest move by Gov. Wolf to fulfill his agenda, particularly his proposal to raise more revenue with a 5% oil and natural gas production tax that’s currently being debated in the general assembly (see Shale Daily, Feb. 11; Jan. 16). The state labor department also said that data would now be reported quarterly, rather than monthly.

Essentially, the state discounted many of the 29 ancillary industries that had been counted in Marcellus employment data under former Republican Gov. Tom Corbett, who was voted out of office last year. Instead, the department will now track employment in six core industry classifications and four related sectors with a widely-used economic model. The roughly 160,000 jobs that seemed to disappear overnight didn’t, sources agreed.

“This is probably right; 250,000 jobs seemed to be a bit of an overstatement, 90,000 seems right,” said Matthew Rousu, an economics professor at Susquehanna University in northeast Pennsylvania who tracks industry employment trends. “It’s still a huge number of jobs created — that’s nearly 1.5% of all workers in the state.

“Under the old definition, the state was sort of overstating things quite a bit, counting something like every trucking job; that’s just not right,” Rousu said. “But a lot of jobs created by drilling have an effect on the broader economy, with workers passing those earnings on to restaurants, hotels and creating additional jobs.”

Responding to the industry’s claims, Wolf spokesman Jeffrey Sheridan referred questions to Goulet. She said “the new methodology was not done in any way to fulfill the governor’s agenda on a severance tax.”

But industry representatives pointed out that Marcellus employment data has always been tracked independently of the governor’s office, with one industry onlooker calling the disagreement a “firestorm.” Tracking began in 2009 under former Democratic Gov. Ed Rendell and the process was tweaked by Corbett’s administration.

“This administration’s words continue to be detached from its actions as it relates to policy matters and enhancing Pennsylvania’s energy leadership,” said Marcellus Shale Coalition President David Spigelmyer. “Why put this important economic analysis in the hands of the governor’s political team rather than relying on career state policy analysts and break from the good government precedent set by both Govs. Rendell and Corbett?”

One source, who wished not to be named discussing a sensitive issue, said the new methodology mischaracterizes how the employment data was previously presented, saying ancillary industries were never characterized as “gas jobs,” but showed how the core industry “directly supported” or made other jobs more secure in the state.

Realignment Plans

In any event, raw state and federal employment data shows that an oil and gas industry retrenchment has occurred in Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia over the last six months following oil’s steep decline. Several producers have also made public their plans to evaluate workforces, cut jobs and gain more operational efficiencies.

In an April analysis, the U.S. Department of Labor said that Oklahoma, North Dakota, Texas and Wyoming have reported consistent job losses in the mining and logging sector, which includes oil and gas extraction (see Shale Daily, May 27). Texas lost a six-year high of 8,300 jobs in the mining sector that month. The DOL said 11 states reported higher unemployment rates in April compared to March, including energy producing states such as West Virginia, Alaska and North Dakota, which reported the sharpest increase.

That trend has persisted through the first six months of the year. In the Appalachian Basin, Consol Energy Inc., Chevron Appalachia LLC and Noble Energy Inc. have publicly announced 352 job cuts since the beginning of the year in response to commodity prices (see Shale Daily, April 10; April 9; Jan 23).

Range Resources Corp. — a top producer in Pennsylvania — announced earlier this year that it would cut 8% of its workforce in the Midcontinent and the company has since closed its Oklahoma City office (see Shale Daily, Feb. 25). Magnum Hunter Resources Corp., which is transitioning to an Appalachian pure-play, has also relocated its corporate headquarters from Houston to Dallas (see Shale Daily, Aug. 11, 2014).

On Thursday, Consol Energy went further, saying they would speed-up a plan first announced last year to stop paying health benefits for more than 4,000 retirees.

“Given the sharp decline in the commodity price environment, we are taking steps to ensure that we keep the company lean and competitive during this challenging period,” said Consol spokesman Brian Aiello. “This and other recent decisions across every facet of the organization are difficult, but necessary as we adapt to challenges currently facing us in the marketplace, and in order to more closely align our business model with that of our peers.”

Several of the Appalachian Basin’s leading producers did not respond to inquiries about whether they plan to cut more jobs later in the year, with some saying only that their previously announced realignment plans have been completed.

Declines

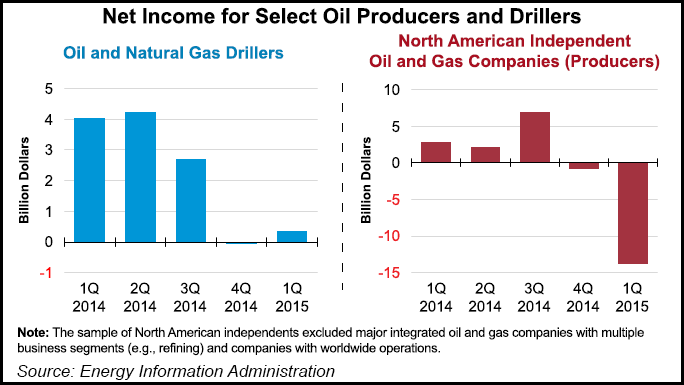

On Thursday, the Energy Information Administration said 57 North American independent oil and gas producers represented in the Nasdaq’s Oil Service Sector Index experienced a collective year-over-year decline in first quarter net income of 574%, going from a profit of $2.9 billion last year to a loss of $13.9 billion this year.

According to state jobs data released Friday, on a seasonally adjusted basis, Pennsylvania’s mining and logging sector lost 1,400 jobs between November 2014 and May, even as the state’s civilian labor force grew considerably to more than 6.4 million during that time. The mining and logging category includes the oil and gas extraction sector, but not related activities such as pipeline construction or natural gas distribution, among others, Goulet said.

West Virginia also lost more than 1,000 jobs in its mining sector between November 2014 and April, while Ohio lost 800 jobs in the sector during the same period, according to seasonally adjusted federal data.

Rousu, the Susquehanna University economics professor, pointed to the change in Pennsylvania’s unemployment rate between April 2014 and May, which went from 6% to 5.4%. During that time, however, unemployment hit a seven-year low of 5% in December, just before companies in the Marcellus began to scale-back sharply in response to the commodity downturn.

“That very well could be from job losses in the natural gas industry,” he said of the slight increase from December to May. “It could be a part of that bump, it would coincide with the slide in oil and gas prices.”

Although December is a historically low month for unemployment with additional seasonal jobs, Rousu compared New Jersey’s current 6.5% unemployment rate with Pennsylvania’s to demonstrate the corollary between natural gas development and job growth over the last decade in the Keystone state.

“Pennsylvania’s [unemployment] rate has always been similar to New Jersey’s, if you look at historical side-by-side graphs, you’d see that,” he said. “But when natural gas development really started to take-off around 2009, the rate was a percent, a percent and a half lower than New Jersey’s and it’s been that way for the last seven years or so.

“Can we say for sure that all of that is because of the Marcellus — no — but most of it makes sense.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |