Canol Shale: Big, Enigmatic, Awaiting Exploration

A colossal natural endowment of northern shale oil — 191 billion bbl — awaits Canadian industry expansion into the central valley of the Mackenzie River, according to government earth scientists.

The mammoth estimate emerged from a review of two geological layers beneath the Northwest Territories. The Canol Shale is estimated to contain 145 billion bbl. The Bluefish Shale is rated at 46 billion bbl.

But the numbers only describe oil in place and no attempt has been made to forecast recoverable volumes or eventual production levels, said a review by the Northwest Territories Geological Survey (NTGS) and the National Energy Board (NEB).

Territorial Industry Minister David Ramsay said, “This study confirms what we have known all along: that there is significant petroleum potential in the Sahtu” central Mackenzie Valley region.

Ramsay also refrained from guessing when the potential might start turning into active exploration and production.

The minister said, “Scientific research in the NWT provides critical data for decision-making about land and resource management. This new research complements the ongoing science to monitor permafrost, seismic activity and water in the region.”

The Canol and Bluefish layers are about 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) north of the border between western Canada and the United States, in a severe climate far beyond all but rudimentary and high-cost access to mainstream North American energy activity.

Industry has acquired 14 exploration licenses in the region since 2010, in exchange for commitments to conduct C$627.5 million (US$500 million) in work on the properties eventually.

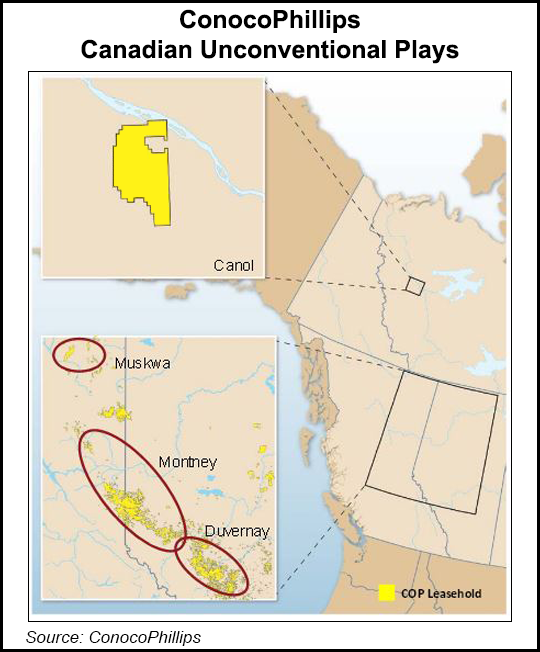

Seven new exploration wells were drilled in 2012-2014. The work culminated in a field trial by ConocoPhillips Canada of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing at a Canol site near the country’s northernmost oilfield at Norman Wells.

Results of the fracking trial, along with the rest of the exploration wells, remain strictly confidential. But no further drilling has been attempted since the experiment during the winter work season of 2013-2014.

The Canol district has a long history of periodically attracting Canadian and U.S. industry interest.

The shale layer is named after a pipeline built from Norman Wells west to the Yukon as an American and Canadian defense collaboration during the Second World War.

Production halted after VJ Day, then resumed in the mid-1980s at a rate of up to about 35,000 b/d, pumped up by artificial islands built in the Mackenzie River and delivered through a new pipeline that Enbridge Inc. installed to northwestern Alberta.

Output from the old wells has fallen off. The pipeline is only about two-thirds full.

Calgary geology, engineering and production firms have predicted that shale development could eventually refill the pipeline — and require construction of another one in its right-of-way — by producing 100,000 b/d or more. But the industry predictions, like the government earth-sciences review, do not set dates or guess oil and gas prices that would be needed to revive northern expansion.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |