Bakken Shale | E&P | Eagle Ford Shale | Marcellus | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | Permian Basin

If Oil Prices Hit $60 WTI, Watch Out For Deluge From Deferred Wells, Says Genscape

Some of the biggest U.S. operators have plans to defer 800-plus onshore wells, which account for close to 400,000 b/d of oil and 528 MMcf/d of natural gas production, but as oil prices slowly have inched up, there’s a real possibility even more production could ramp up this summer, according to Genscape Inc.

The crude oil contango market in the United States created a big incentive to store oil, using the wellbores for the uncompleted wells, said Genscape’s Randall Collum, managing director of supply side analytics. He told NGI’s Shale Daily on Thursday that well deferrals were announced during 4Q2014 conference calls by a who’s who of onshore operators, including Anadarko Petroleum Corp., Apache Corp., Cabot Oil & Gas Corp., Chesapeake Energy Corp., EOG Resources Inc. and SM Energy.

Collum and Genscape’s Ben Chu, senior supply consultant, estimated that those producers’ drilled-but-uncompleted (DUC) inventory accounted for about 373,000 b/d of oil and more than 0.5 Bcf/d of gas. While traditional oil hubs in the United States are at record-high levels, there is a lot of production awaiting a place to land. It’s a combination of a lack of storage, and a lack of finances, in some cases, Collum said. Completion costs can be as much as 65-70% of the total well costs.

Exploration and production companies instead are conserving capital “by doing one thing: drilling wells but deferring completions,” he said. They are “solving for the contango in the crude curve, factoring in expectations of lower service costs because of lower oil prices and the need to meet drilling rig and lease drilling commitments, while also conserving capital.”

Other analysts estimated that in March there are about 3,000 DUCs across the country.

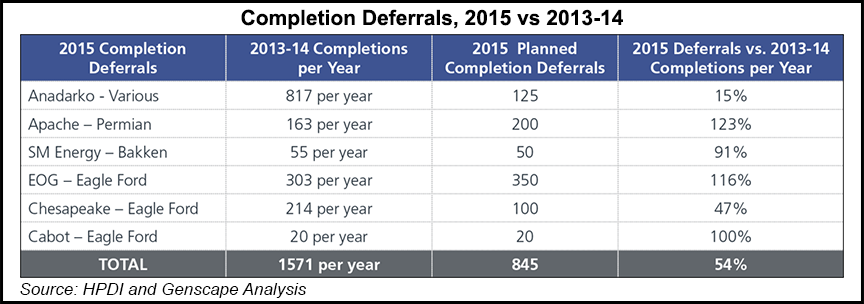

The uncompleted wells for the six independents tracked by Genscape as of last month accounted for 845 deferrals in the Eagle Ford and Bakken shales, Wattenberg field and Permian Basin. In addition, Continental Resources Inc. after the first quarter deferred 25% of its completions in the Bakken from previously planned levels of completion activity.

“The impact of these 845 deferrals, if they were to all come online in the same month, would be about 373 Mb/d of oil and 528 MMcf/d of gas,” Collum said. “Using a rough rule of thumb that the first 12 months of a new horizontal well averages approximately 50% of first full month initial production, the impact over 12 months of production would be approximately 68 million bbl of oil and 96 Bcf of gas.”

Notably, the companies with announced DUCs “are relatively big companies. They’re all in good financial shape, too. It means they’re reacting more to economics and what the economics tell them to do.” However, “the smaller guys need some kind of cash flow to keep going. I think they really can’t handle drilling some wells and spending the money and not actually completing them because that gets production coming with cash flow.” Without the cash flow, the small operators’ financial outlooks “probably decline way too quickly.”

Drilling isn’t being done to hold leases by production. “The whole theory behind it is, producers already got these rigs on term contracts. They’ve got to spend the money on rigs no matter what.” So, it’s either pay the dayrate penalty on the idled rig, “or go ahead and drill and have the wells parked and ready,” he said. When the wells are “ready economically to go complete them, they can.

“There is also the question of organizational capability. For a company whose drilling department in a particular play is now drilling very efficiently — it’s an expensive proposition to ramp that entire department down and ramp it back up later, hoping for the same efficiencies. The learning curve has already been paid for.”

Hess Corp. in the Bakken applies this thinking to its completions department as well, “so despite the numbers in the economics suggesting their wells are overall marginal in the area and would benefit from higher futures prices, we can see different players still choosing to approach it a little differently, and we track this.”

Genscape’s economic models about a month ago indicated that when the oil price declined to $45/bbl West Texas Intermediate (WTI), most of the Eagle Ford and Bakken oil plays were priced out of the market, except for the core of the cores. As an example, EOG’s Eagle Ford leasehold, which is in the core of the play, is one of the companies monitored by Genscape.

“With today’s prices, EOG’s returns are marginal given the uncertainties,” Collum said. “Payback is either 46 months with an IRR [internal rate of return] of 16%, or never and minus 2% IRR, if the $45 WTI price were to persist. Deferring completions and receiving the improved pricing in the forward curve not only saves them capital this year but would pay back the well investment slightly faster.”

However, the slight uptick in the oil price has led at least one producer, Apache, to indicate on April 1 that it would not defer completions, and because of lower service costs, all of the wells it is drilling today are being completed.

At $55.00/bbl oil, some of the DUCs “make sense to drill,” Collum said. “If we hit $60, I don’t think there will be any deferrals. I think they will all be gone…Even as the prices have risen here recently, the contango has started to narrow. Whereas a month ago we were $10.00 to $12.00 a year out, now we’re only $7.00 out. As that contango narrows, there’s less incentive to defer wells.”

If producers are becoming more confident about oil prices, expect to see a surge in production over the next few months, Collum said. Last month he said the U.S. rig count probably would bottom in August and begin to rebound from there (see Shale Daily,March 27). Gas production was expected to peak in May-June, with oil production peaking in the June timeframe.

However, “I think if prices rebound too quickly, then you might not see too much decline later this year,” Collum said. “You still have .5 Bcf/d less production from the Marcellus Shale,” with Chesapeake and Seneca Resources Corp. separately planning to shut in output through this year.

If the deferrals go away, that’s another 0.5 Bcf/d of gas. “And then there’s 400,000 b/d of oil” that would come back online once wells now waiting for completion ramp up. What would follow? “prices will go back down, right?”

Bringing on the DUCs would “just keep production propped up,” he said. “You may not get the responses needed. But production is going to respond to what the market tells it to do. That’s basically what it’s doing right now.” The producers are using their wells as storage because the contango in the market “told them that’s what they needed to do.”

Collum said earlier this month he spoke with some small Eagle Ford operators in South Texas. One “mom and pop” producer, with about 20 wells in the area, has oil output that normally was averaging 80-100 b/d of oil. Not so today.

“He said even on the small wells, they’re choking them back because of the oil price environment, the contango in the curve,” Collum said. “So those wells that normally flow 80-100 b/d they’ve had to choke back to 20-40 b/d because the prices just aren’t there. There’s nowhere to sell it because of the low prices. If they produce it and sit it on the tank, they’ve got to pay taxes on it. So they’re choking it back so they won’t have to do all that.”

IHS Inc. researchers analyzed DUCs in the Eagle Ford, which they estimated at about 1,400 total. They found that the DUCs could be converted to producing assets for about 65% of the cost of a new drill, which would lower the economics when evaluated against remaining costs.

“In this low oil price environment, operators in the Eagle Ford and other U.S. shale plays are focused on optimizing the value of their assets and managing their costs, and these drilled, but uncompleted wells enable them to do that more effectively for several reasons,” said IHS Energy’s Raoul LeBlanc, senior director of research and lead author of the DUC analysis.

“First, the drilling costs of these wells were already incurred by operators prior to 2015, and the completion costs, which comprise the majority of well costs, can be negotiated at a cheaper rate since completion crews are now both available and available at cheaper rates. Second, if completion costs are fairly consistent in the play, then it stands to reason that wells with higher production will yield better returns on capital.”

Because of the shortened lead time to convert DUCs and the lower incremental costs of generating production from a DUC well, operators likely would have incentives to work through the uncompleted well inventory, according to IHS.

To estimate the implication of these wells on 2015 production rates, IHS researchers ran different conversion scenarios to assess the outcomes of bringing onstream 50, 100 and 150 DUC wells every month. Considering the need for a steady-state inventory of about 300 DUCs at all times, the study found that roughly 1,100 should be available for conversion. If the low-case conversion rate of 50 wells per month were achieved, IHS estimated that the DUC wedge (incremental) production would be 123,000 b/d at the end of a year, while a high-case conversion rate of 150 would result in 269,000 b/d after 12 months.

“The volumes of these DUCs that are converted are meaningful because our IHS analysis indicates that the Eagle Ford DUC wedge production alone could generate an additional 180,000 b/d in the second half of 2015,” chief upstream strategist Robert Fryklund, who co-authored the DUC analysis. “That additional potential production represents approximately 14% of the play’s annual production of 1.25 million b/d. This further supports our IHS view that oil price fundamentals will face headwinds despite the collapsing rig count, and that a material price increase could lead to a supply response in late 2015 and 2016.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |