Markets | E&P | LNG | NGI All News Access | NGI Data | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Appalachia Glut Not Likely to Usurp Henry Hub, Says NGI Natural Gas Price Expert

The Appalachia Basin may be the mightiest natural gas producing area in the country today, but the chances that it will overtake Henry Hub as the national pricing point are “virtually nil,” NGI‘s director of strategy and research said Tuesday.

Some pundits have suggested that overwhelming gas production from the Marcellus/Utica shales has made Appalachia the price proxy. However, it takes more than a lot of production to set the dominant landing price, said NGI‘s Patrick Rau. He and Observ Commodities founder Wei Chien shared some observations during a 45-minute webinar, a replay of which is available on the NGI website at: /webinar.

For all the talk that Henry Hub is no longer in fashion, Rau said the data show otherwise. Appalachia in fact has not rendered Henry Hub irrelevant, he said. Henry Hub is “still a decent proxy for other producing regions,” and it “should remain the reference point for basis trading.”

Rau and his team of researchers ran some scenarios using NGI data since 2006 to determine how gas trading has evolved with the advent of Marcellus Shale and lately Utica Shale gas. Henry Hub helped to establish the New York Mercantile Exchange (Nymex) futures contract, but with unconventional drilling, a lot has changed. However, some things won’t change, Rau said.

“Appalachia is not the national pricing point” and it’s unlikely to become the landing point, Rau said. The Northeast basin may have taken a lot of Henry Hub market share, but the truth is, Appalachia remains “on the “lower end of pricing” and it still doesn’t hold the dominant share of domestic output.

“First of all, the Appalachia still only represents about 20% of total U.S. production,” he noted. “That’s certainly in the minority. But the Appalachia is also the one area that’s consistently been the lowest priced area of gas in the U.S. According to forward curves, it should continue to be on the lower end of pricing of natural gas…

“To say that the Appalachia is representative of the entire country from a production or a pricing standpoint, it certainly isn’t.”

The crux of the argument centers around the big switch in where gas is produced in the United States. Appalachian gas output grew from less than 6% of domestic production in 2006 to more than 20% in 2014. The Gulf of Mexico (GOM) in the 1990s represented around 25% of total U.S. gas production; today it’s about 5%.

That turnaround “certainly legitimizes the question,” about Appalachia market strength, said Rau. “Asked differently, has the emergence of the Appalachia decreased the relevancy of the Henry Hub?”

To get the answer, Rau and his team combined Gulf Coast gas production — all of Texas and Louisiana — with GOM gas output “because I still believe that the Henry Hub serves as a reasonable proxy for the price of production for the entire area. There is a basis differential between Northern Louisiana [and Texas] and the Henry Hub, but the emergence of…the Haynesville Shale, the Barnett Shale, the Eagle Ford and the Permian is what’s kept the Gulf Coast relevant.

“But even when you add in all those increases in unconventional sources, Appalachia still is growing and the Gulf Coast still has declined in terms of total production.” Combined Gulf Coast/GOM gas output has fallen from about 50% of gas output in 2006 to about 40% in 2014.

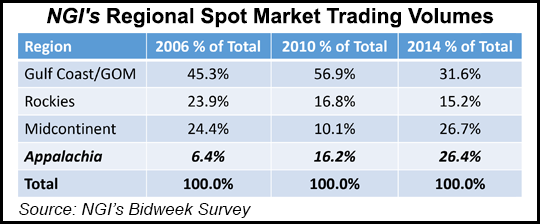

The NGI team used spot market trading data taken from NGI’s bidweek survey since 2006. Appalachia in 2006 represented a little more than 6% of total traded volumes. It was up to 26% last year. The combined Gulf Coast/GOM area has fallen from about 45% of reported volumes in 2006 to around 30% in 2014.

With the unconventional revolution and the resulting increase in 3P reserves — proved, probable and possible — a lot of the risk factor that the United States is going to run out of gas has been priced out of the market, Rau noted.

“That’s reflected in much lower volatility at the Henry Hub. But that’s not to say that there is no volatility in the U.S. natural gas market. It’s far from that. We think that the volatility has been pushed out to regional markets. Nowhere has that been more the case than in New England,” he said, citing the Algonquin Citygate. There, volatility has increased dramatically over the last eight-plus years. “There’s clearly been an uptrend line.”

Volatility creep also has occurred in the Chicago Citygate, particularly in the last couple of winters, and volatility should continue as new gas, mostly from Appalachia, enters the region. In addition, Appalachia volatility has risen.

“The chances of Appalachia taking over as the point of reference for U.S. basis trading is virtually nil,” Rau said. “There’s not much chance at all.” Henry Hub is “interwoven into the fabric of this industry…There are far too many physical and financial contracts tied to the Henry Hub,” and switching would be costly. Contracts would have to be renegotiated and revised, and back office functions would have to be updated.

In addition, Henry Hub already is positioned to handle future U.S. liquefied natural gas export activity, making it “likely to be a pricing point for international pricing by the end of the decade.”

The Northeast gas glut has impacted Henry Hub, however. In 2006, Henry Hub prices represented about 110% of the actual realized price of production throughout the United States, according to NGI calculations. To calculate realized production prices, production volumes reported by the Energy Information Administration were multiplied using NGI’s historical bidweek prices. The same method was used to calculate forward prices by extrapolating what production could be if that output continued at its historical trend line growth rates. Every area was calculated, with Appalachia output assumed to grow by about 5% a year.

“What we found is that the Henry Hub price represented about 1.1 times the U.S. price in 2006,” Rau said. “And we think that it’s going to return to that range going forward.”

Appalachia has overtaken Henry in one big respect: it is the marginal production area in the United States.

“I think clearly the answer to that is yes, it has,” Rau said. “Marcellus/Utica gas production has grown by very, very high rates lately. It’s the fastest growth that we’ve seen in this country, so it is the marginal production area.”

However, Appalachia production growth is declining — not turning negative, just slowing down. “Large numbers problems” loom for the Northeast, Rau warned. “The faster and more that absolute production in the Marcellus and Utica grows, simply the more difficult it’s going to be to grow it year-over-year.”

Year-over-year gas production growth actually began declining in the Northeast basin in 2011. Extending the Appalachia production trend line out, Rau’s team determined that negative year/year production growth may occur after 2016.

But “this is a very simplistic argument,” he said. Appalachia gas output won’t be at a loss after 2016. “We don’t believe that. We expect it to continue to grow. But it’s not going to continue to grow at the historical rate that it has.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |