Demand Has Fingerprints on Oil Price Crash, IHS Exec Says

Even though overly robust production is the prime suspect, it may have had an accomplice — weak demand — in last year’s mugging of global crude oil prices, according to an executive with consultancy IHS.

“Weaker demand globally did play a role,” said Jim Burkhard, vice president and head of global oil market research and energy scenarios at IHS, speaking on a recent panel discussion hosted by the Center for Strategic and Informative Studies (CSIS). “If demand had been what many expected in 2014, would we have had the price collapse?” Demand’s role cannot be ignored in an analysis of the supply glut, he said.

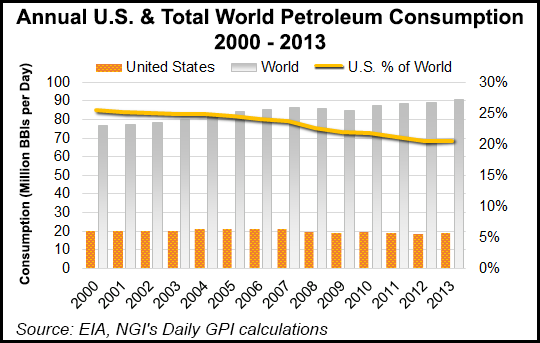

Oil demand globally today is half of what it was in 2000, according to Burkhard, who shared the panel with two other speakers who talked about overall market dynamics and supply. The common measurement on the demand side looks at how much oil is required to generate a given amount of economic output (in dollars).

“When you compare that [metric] to 2000, it is less than half of what it was then today,” Burkhard said, meaning “the oil intensity of the world economy is declining as it has been for a long time, and it is continuing to go down.” It is a function of global economic growth far outpacing global oil demand growth, he said.

There has been a long-term trend of decelerating global oil demand growth. Burkhard raised the question of how oil demand will respond to lower prices, noting conventional wisdom would expect low gasoline prices to cause a ramp-up of demand. He said he doesn’t think that will happen.

Burkhard looks at the two predominant oil demand areas in the world: the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which includes North America, Europe, Japan and South Korea, and China by itself. OECD accounts for half the world’s liquid energy demand, he said, and its demand peaked in 2005 and hasn’t been exceeded since due to fuel efficiency and climate change policies.

“All the major economies have fuel economy standards,” Burkhard said. “In addition, population growth is slowing and populations are aging in many key markets around the world.”

Noting that there will always be “demand shocks,” unexpected surges, such as what happened in Japan after the nuclear plant disaster in 2011, Burkhard said these will be relative blips compared to the long-term backdrop of deceleration of global oil demand.

“Generally, the most important variable in energy demand is global economic growth, and in the United States we appear to be in pretty good shape, so U.S. oil demand could grow this year above what it was last,” he said. “It probably will, but not by a huge amount.”

An additional aspect of possible impacts from the low oil prices in the United States is in the future growth of new energy infrastructure. In a $100/bbl environment this infrastructure growth has been robust, but what happens now, CSIS Director Sarah Ladislaw, who moderated the panel, asked Burkhard and another speaker, Rusty Braziel, founder of RBN Energy Inc.

Braziel thinks that U.S. energy infrastructure growth was going to be slowing before the oil price crash, but he doesn’t think it will slow all that much now that prices have crashed. “One of the things we have not seen in our business is a lack of interest in investors,” Braziel said. “We’re seeing vulture capitalists coming out of the woodwork, so we might be surprised, and this low-price environment might actually turn out to be a good thing for infrastructure investment.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 |