E&P | Daily GPI | LNG Insight | NGI All News Access | NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report

Argentina’s Vaca Muerta May Fuel Central America’s LNG-to-Power Market Growth

Central America and the Caribbean could see growth in natural gas demand expand as environmental policies are enacted and as Argentina’s exports ramp up.

“Most of the countries in the region have plans to diversify their energy mix by focusing on renewables and new gas-fired projects,” said Wood Mackenzie’s Mauro Chavez Rodriguez, principal analyst, at the recent Gastech 2019 conference in Houston.

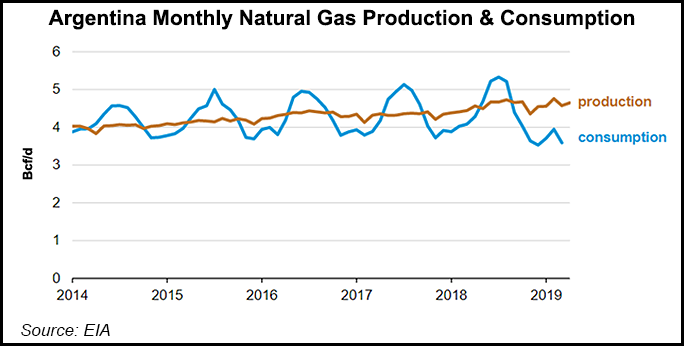

Argentina is far and away the natural gas production king, and is on its way to becoming self sufficient with the Vaca Muerta formation underpinning consumption. There are enough reserves in the basin to help consumption in neighboring countries and overseas via liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports, which could be less expensive than U.S. gas.

The GNL Escobar import terminal, which has direct access to the Buenos Aires region and the country’s natural gas grid, could over the next five years “be enough to cover winter’s peak LNG demand,” Rodriguez said.

Argentina today is the “only country in Latin American investing in gas pipelines,” and it now is able to export gas from the Tango floating LNG production barge at the BahÃa Blanca port. The exports would “basically be supported by seasonal oversupply in summer.”

Besides supplying its Latin American neighbors, the country’s gas stream also may find a welcome home in Asia, as peak potential LNG production during the summer months “coincides with strong winter demand from utilities in Asia. This seasonal dynamic could attract Asian buyers and present a strong economic case for Argentinian LNG.”

What’s key are the costs.

Argentina’s LNG has a lower shipping cost to reach Asian markets than U.S. Gulf Coast facilities as it would avoid potential Panama Canal congestion, Rodriguez said.

“Supported by the Vaca Muerta, Argentina’s production in the Neuquén Basin will ramp up over the next few years, with major scale LNG production expected to begin in 2024,” he noted. Wood Mackenzie is forecasting the country’s LNG production volumes may reach 6 mmty by 2024 and increase to 10 mmty by 2030.

Associated gas from Vaca Muerta also is forecast to represent 15% of the country’s gas production by 2024. In addition, condensate and dry gas window projects, with breakevens below $3/MMBtu, are set to ramp in the next few years. The lack of underground gas storage facilities near demand centers in Argentina means that gas flow to potential export terminals also would be seasonal.

Despite other price challenges posed by the seasonal use of LNG plants, Wood Mackenzie is estimating breakevens for Argentina LNG of $8/MMBtu at delivery ex ship for Japan, which means the seller’s obligation ends when the LNG is on board the ship.

“Vaca Muerta’s gas production has dramatically changed the outlook for Argentinian gas,” Rodriguez said. “It is already bringing cheap gas for local industry and also supporting the construction of new major gas pipelines.”

However, Argentina’s gas demand and neighboring exports to Chile and Brazil may not be enough for the Vaca Muerta’s gas potential. “LNG exports could be a solution that enables Vaca Muerta’s production to continue the growth story.”

Argentina’s gas exports “could be interesting to players who want to diversify supply outside North America,” he said. “The seasonality of its output could be also seen as a virtue for Asian utilities that are looking to contract just for their peaking demand months in the northern hemisphere.”

Asian players already have placed their flags in the Vaca Muerta. Five years ago, Argentina’s state-owned YPF SA and Malaysia’s Petronas teamed up and now partner in the La Amarga Chica joint venture. In 2017, BP plc and Bridas Corp., a 50-50 venture of Bridas Energy Holdings and China’s CNOOC Ltd., created Argentina’s largest privately owned integrated producer, Pan American Energy Group, to work in the Aguada Pichana Oeste.

“Meanwhile, Qatar Petroleum recently has shown interest in Argentina, buying a stake of ExxonMobil’s business unit in that country, and also partnering for exploration offshore,” Rodriguez said. “We see further opportunities for Asian players looking for foreign investment, not only in upstream but also for major midstream infrastructure, such as gas processing plants, pipelines, petrochemicals and LNG export plants.”

Argentina is not the only country with energy resources, Rodriguez noted. Brazil is likely to prosper as associated gas volumes grow from its pre-salt formations. For other countries, the move to alternative energy from oil is growing.

“Even when oil dominates power generation, LNG-to-power looks promising, due to high uncontracted LNG needs and the low flexibility required by most of the countries,” he said.

However, Latin America and the Caribbean nations overall may have “mixed fortunes for LNG demand.”

Across the region, Wood Mackenzie expects LNG to grow to around 15 mmty by 2025 from 4 mmty this year. Under “regular” hydro conditions to 2025, however, LNG demand should decline in the Southern Cone, defined as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay and Uruguay. In that region, LNG consumption is forecast to shrink from 5 mmty to 2 mmty.

Vaca Muerta output should increase, while associated gas volumes are seen climbing in Brazil’s pre-salt deposits.

During the Southern Hemisphere’s winter, “Chile and Argentina will require LNG,” said Rodriguez, while in Brazil and Colombia, “interruptible LNG solutions will be needed to deal with adverse hydro conditions. This flexibility will have a premium price.”

The Southern Cone has enough existing regasification terminals “to cope with the future LNG demand,” but opportunities for more terminals could be in the offing for Colombia’s largest port city in Buenaventura, as well as in the Caribbean.

LNG-to-power looks most promising today in Colombia, as its oil production is in decline, Rodriguez noted.

Colombia is expected to lead the region for LNG-to-power with more than 10 mmty by 2025. Brazil is another potential customer for growing LNG-to-power, and Panama is stepping up its gas generation use.

“Panama is on its way to incorporate 1.5 GW of additional gas-fired capacity with three highly efficient combined-cycle plants” between 2018 and 2023, Rodriguez said. The AES Colon 381 MW plant was commissioned in 2018. Sinolam’s 441 MW plant is on track for start up in late 2020, and Royal Dutch Shell plc has a 15-year supply contract. In addition, NG Power’s 621 MW plant is under construction with a 2023 startup planned.

Chile, which is decommissioning its coal power plants, also could see gas demand increase in the next five years, with Wood Mackenzie estimating consumption up by 6%/year.

The amount of rain each country receives should drive LNG demand too. “Despite the rise of renewables and their impact on demand and seasonality, hydrology will still drive LNG imports.”

To take advantage of the thirst for gas, Rodriguez said producers working the Vaca Muerta and Brazil, including Royal Dutch Shell plc, Equinor SA, Total SA and Repsol SA, “will leverage their own LNG portfolio positions to support both flexibility and security for new gas supply agreements in Latin America.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2577-9966 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |